There’s little quibbling over what the inciting action in this film might be. It’s titled Accident for a reason. The serenity of an English home is disrupted by screeching tires and then a horrendous, blood-curdling crash following in its wake.

But the sequence is as much indebted to silence as it is noise. All the time director Joseph Losey chooses to immediately call on his audience’s sense of imagination. All we see is the home. Not the car, not the circumstances; at least not initially.

The opening is a textbook example of using what’s not there to his advantage. Because instead of showing the grisly accident, Losey stays neatly framed on this grand manor. Compositionally, he knows full well what he’s doing. We can trust we are in capable hands from thenceforward.

While the title might be easy, the rest of the picture is a hard-fought, slow-burning exercise in destructive relationships. Though this is a study of the middle-class malaise, it’s indicative of an entire society — even an entire world — disillusioned by the way history has turned.

The aftermath of the car crash is all we are allowed. A man (Dirk Bogarde) — we can gather the man of the house — wanders out to find a car flipped on its side. I’m admittedly not well-accustomed to Dirk Bogarde. I am predisposed to believe him to be out of the mode of James Mason, perhaps slightly more maladjusted — still, his elder fell for a younger girl in Kubrick’s Lolita as well.

The other figure of interest is a young woman (Jacqueline Sassard), nearly catatonic, first climbing out of the car, treading on the face of her dead companion, then slumping her way across the front lawn. We have yet to fully comprehend the dramatic situation nor how these people relate to one another.

The film’s screenplay is realized by famed playwright Harold Pinter though adapted from someone else’s work (Nicholas Mosley). As distilled by his pen, it is all about subtleties and subtext. The performances, as a result, are so restrained — even painfully so — and they fit a world without dramatic musical cues and few cathartic moments of emotional release.

Likewise, it enlists a morose, often drab color scheme of mostly cool blues and grays, highlighted every now and then by lacquered wood desks and door frames. As the film progresses into more mundane scenes, I almost want to compare them with Yasujiro Ozu’s whether drinks or bottles placed in a room or shots of color drawing one’s eye. There is a pleasing attention to detail in such scenes which for all other reasons are the height of banality.

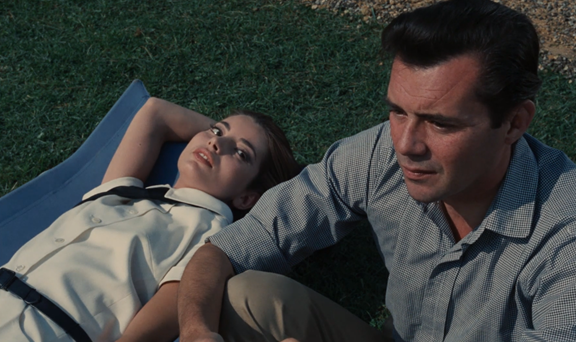

This is, of course, a story rooted in the past where context can come into play to help elucidate the present. It feels all but necessary. At an earlier time, we meet Stephen (Bogarde), an academic and well-regarded tutor. His pupils include the charming William (Michael York) and the strikingly beautiful heir to Austrian royalty, Anna (Sassard). There’s little question love is in the air. At this point, it feels youthful and innocent.

Likewise, the professor returns home for evenings reading stories to his two adorable children as his gently ribbing wife (Vivien Merchant) works nearby, currently pregnant with their third child. There is a sense this family represents all that is fine and upright about the British middle class.

The film continues to remain minimalist and casually laid back. What follows are moments on a punting expedition which are nevertheless injected with a sleepy sensuality playing out between the trio: the tutor and his pupils. Next, they’re over for lunch and the prospect of a lazy afternoon of lounging and tennis.

Stephen’s dorky and slightly conniving colleague, Charley (Stanley Baker), invites himself along for the festivities. There’s a sense he wants to be in on this, and he proves to be hardly as innocent as he lets on. But we have yet to realize exactly why.

Instead, we can content ourselves with what Losey is building around us as we watch. One particular technique is to start in a close-up only to pull back on that space which instantly becomes a focal point of a far larger canvass. Not only is it slightly disorientating but it does very intentionally guide our focus. It cannot help but direct our eyes.

There must come a point of no return as the picture enters its most stylish and enigmatic phase, which subsequently becomes the most devastating. With his wife away having the baby, Stephen inexplicably meets an old flame (Delphine Seyrig) and proves himself to be a closet cad, confirming our earlier suspicions.

Except the scenes with the other woman — the daughter of the Provost — extend the sense of dream-like reverie by foregoing typical back and forth dialogue over images. Instead, their patter is conceived in voiceover — nonchalant and smooth. Perfect for denoting the falsity of such a romantic fantasy. It cannot last.

Then, he comes home to find quite the jarring surprise but resorting to its usual tendencies, the ousting of Charley and Anna in a tryst results in less confrontation and even fewer emotions.

It’s like they are constantly being drawn further and further in, cold and impregnable. Stephen’s own detachment might come from catching them in a situation that he just experienced himself. He’s no innocent bystander. There can be no surprise or condemnation because it’s just like looking in the mirror. All he can do is resign himself to passive receptivity.

The depressive atmosphere of this world is irrepressible, reflecting the privileged elite with their frivolous diversions and usual lethargy mixed with deleterious desires. Thus, Accident is distressing, not due to any matter of pacing as much as it is the intentions of the characters themselves. The male characters in particular.

Jacqueline Sassard, as beautiful as she is, does feel mostly like an object of affection in the vein of a Vertigo or other such pictures. Where all the men are ogling over her, secretly dreaming of time spent with her alone. This is indicative of the poison going through the majority of their romantic relationships. If youth has yet to be sullied, as represented by the callow Michael York, middle-age has certainly tainted masculinity.

To the very last zenith, Accident remains the epitome of a slow, torturous burn of a movie that by some form of insanity, manages to end just as it began, almost as if nothing has happened and no change has been enacted. Because what is insanity if not something horrendous happening and then nothing being done to prevent it from happening again? It’s a mad spiral of destruction.

The only thing that makes it worse is the lack of concern. There is no emotional well to be dug into. It’s simultaneously the most perturbing and compelling element of Losey’s work here. It says so much by saying very little at all.

4/5 Stars

Beautifully written. I’ve never seen this film, but have always been aware of it; now I’m interested. Never been much of a fan of Bogarde as an actor (interesting person, though), but I do like Baker and York in anything. We’re fortunate here in Portland to have a video store with 80,000 titles in it (Movie Madness), so I now have another excuse to drop $3.00 there. Thanx,Mark

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the kind words. That’s wonderful you still have that resource. Sadly it feels like they are generally disappearing even as obscure movies are slightly easier to find. Regardless, you no doubt lose some of the enjoyment in the search.

LikeLike