The story goes Peter Bogdanovich met Roger Corman sitting in a screening of Bay of Angels (1963). What came out of that was an apprenticeship of sorts on Wild Angels (1966) in the Corman Film School where Bogdanovich did everything you could possibly imagine from script doctoring to location scouting etc. What he got for his troubles was hands-on experience but also the chance to direct his first feature…with a couple stipulations.

Corman gave him full control of his own movie as long as he reused some footage from an earlier Boris Karloff picture, The Terror, as well as utilizing the veteran actor’s two days of service he still owed Corman. There you have the birth of Targets, which manages to amount to far more than these contrived beginnings might suggest.

Because Bogdanovich found a way to make these haphazard pieces work — where it feels more like a meditation than a constraint — and the movie uses this to its advantage. It’s like a ’60s rendition of the poverty row pictures of the ’40s where necessity is truly the mother of invention. Sometimes you get a diamond in the rough.

The irony is while the big pictures were giving us entertainment that would become emblematic of the times like The Graduate, Bonnie & Clyde, or 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s a movie like Targets placing us in the times themselves. In this way, it functions more like contemporary television.

What we are provided is a very concrete sense of Reseda in 67-68. There’s the “Real” Don Steele on the radio waves. Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder is a modern classic featured as the Saturday night movie on channel 7. A family sits down in the evening together to take in Joey Bishop and sidekick Regis Philbin. And, of course, there are drive-ins.

If this sets the stage and places Bobby Thompson (No, not the ballplayer) in a vaguely familiar landscape, the movie itself comes flowing out of the persona Boris Karloff provides free of charge.

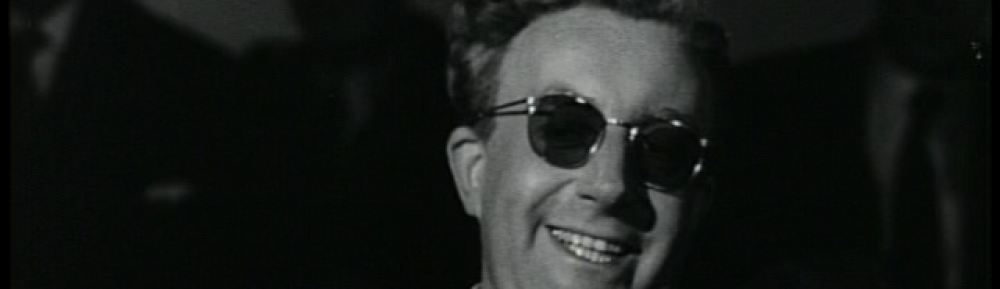

Looking at them without context, there are so many elements of Targets that might leave one mystified. For instance, this white-haired gent with the booming voice. If you put the movie in a time capsule, those who find it probably wouldn’t know this is Boris Karloff. His Byron Orlok isn’t an anagram, but it feels like one.

Although he’s an acclaimed name, he’s resigned himself to a sorry fate. In his own words, “I’m an antique, out of date — an anachronism. The world belongs to the young. Make way for them, let them have it.” He might have seen Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate too.

Still, he’s continually in dialogue with his own personal legacy and very aware of it. Just as he watches a version of himself on TV. His character recalls a tagline from his heyday, “The Marx Brothers make you laugh. Garbo makes you swoon. Orlok makes you scream.” It’s all part of this persona closely mirroring Karloff’s past.

Likewise, Sammy — that guy’s not much of an actor — although it changes instantly if we know this is Bogdanovich himself. The young screenwriter walks in, sees the TV, and right on the nose says, “It’s Criminal Code. I saw this at the Museum of Modern Art. Howard Hawks directed this. He really knows how to tell a story.”

They become these dueling pawns, partly fiction, partly reality, as Orlok bemoans the fact he has become high camp; he can hardly play it straight anymore, and Sammy coaxes him that the role is something he can do (Targets?). Otherwise, he’ll offer it to Vincent Price.

It’s as if the director beat Orson Welles to the punch with this kind of intratextual dialogue between the medium and its real-life players. Surely history helped out because Targets was just his beginning followed by a whole slew of classics, albeit disrupted and undermined by his own turbulence and troubles replicating his most supernal successes. All these things and more are what make Targets so riveting when it has little right to be.

Orlok’s secretary Jenny (Nancy Hsueh in a charming role) is romantically attached to Sammy, but also has a staunch devotion to Orlok. She doesn’t want the old man to just give up and she feels slighted when he lashes out at her — one of the few people who genuinely cares for his well-being.

He’s ready to turn his back on it all only to reluctantly agree to make a public appearance. He’s fallen to the low of the Drive-in Theater circuit, living off the residual celebrity of his waning fame.

Meanwhile, Bobby has gone through his daily paces. He seems like an All-American boy. He’s married but lives with his parents. He likes guns, and he’s been taught a healthy (or unhealthy) sense of competition. There’s an underlying angst supplied by this deceptively pristine life.

He stakes out on top of an oil well, brown bag and a soda pop in hand, as he sets up overlooking the freeway, prepared to pick some people off. Bogdanovich captures the evolving sequence with a Sam Fuller sense of grab-and-go photography, on the side of the freeway, with a brazen even outlandish sense of drama.

This is real traffic and real places and the director plucks out his shots from these pregnant moments of simulated reality. Between the crosshairs, gunshots, swerving vehicles, and flailing bodies. The scene evokes the Texas tower shooting of 1966 where killing becomes this indiscriminate force of violence.

The Sniper (1952), from over a decade prior, was a picture that, no matter its effectiveness, was meant to elicit a social response. Stanley Kramer’s movies can be strongly identified by this sense of responsibility toward the viewer. Targets hardly feels like a political statement of any kind, but its themes are no less intriguing — probably because it never feels like it’s preaching something. Instead, it allows us to consider its various digressions and still be gripped.

The drive-in finale actually does a solid job of reconciling the two disparate story strands. Bogdanovich had watched enough Hitchcock, heck, he’d interviewed the Master of Suspense, and put in this position calling for such a setpiece, he seems to know intuitively what he has to do.

What’s more, it signaled the young director’s ascension as a New Hollywood darling. What’s so striking is how it marries Classic Hollywood with the contemporary climate and does it with a startling sense of command. If you needed a picture to try and sum up Bogdanovich himself, then there is no better lodestone.

He wants to revel in the days of Karloff and Hawks of old — when violence meant monsters and gangsters — and yet he brings it into the 60s. Because violence still existed but in a different form. In the age of social tumult and assassinations, the landscape of the 1960s feels a lot more futile and incomprehensible.

And the images make you shutter as we are implicated in this alongside a killer even as we sympathize with Orlok trying to bow out gracefully. I’m not sure which aspect is more telling. The power is that we need not pick between them. We are presented horror in its various forms, old versus new, and the person who unifies them so evocatively for us is Peter Bogdanovich. It’s quite a stunning feat of ingenuity.

4/5 Stars

Best-written review of this I’ve ever read: hats off, Mark

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s very kind of you Mark! Sometimes I wonder if I had enough time to edit everything, but I’m glad you enjoyed it. It’s encouraging. There’s a great deal about Targets that’s really stuck with me.

LikeLike