Seeing the Twin Towers on celluloid always brings a bit of a wistful reaction because there presence represents so much. It feels like a line in the sand and there are those who know that far better than me. The last time I recall having this sense was watching Peter Bogdanovich’s They All Laughed, and it’s little surprise The Thing Called Love begins with a very similar visual shorthand.

It says so much in a matter of moments as we watch Miranda Presley (Samantha Mathis) wearing her Yankees baseball cap, ride the greyhound bus with her guitar case by her side. Bogdanovich returns to another salient element of They All Laughed because The Thing Called Love is also a film enmeshed in the country music scene. New York might feel like an unusual mecca, but Nashville is not. That’s where Presley (no relation to Elvis) is heading. She’s got grand aspirations like so many wide-eyed dreamers.

Our hearts drop a little bit when the bus pulls into the parking lot of the Bluebird Cafe. It’s given the start to many fledgling talents and yet the line of eager musicians ready to audition quashes any optimistic expectations. Miranda’s no doubt destined for an arduous journey ahead.

Mathis and her real-life boyfriend at the time, River Phoenix have a meet-cute born out of circumstance. He jumps out of his truck late for the weekly auditions and pulls her into his lie so they can squeeze into the lineup. She doesn’t take kindly to his tactics and let’s him know.

It would be so easy to dismiss or even roll your eyes at these obligatory moments in the script. They feel to clean and conventional, but somehow the metanarrative and the candor of the young performers make it feel worthwhile.

Miranda gets her first rejection only to fall in with a community of her peers. She meets her momentary acquaintance James Wright (Phoenix) when he does a rendition of his tune “Lone Star State of Mind.” The track was actually written by Phoenix himself, an enthusiastic musician in his own right.

Their relationship is one mostly born of looks and mysterious glances that suggest so much in a way that is tantalizing and hardly anchored. Meanwhile, the Stetson-wearing Kyle (Dermot Mulraney) takes an immediate shine for Miranda, and it reveals itself through candid conversation and encouragement. Perhaps she knows as much as anyone else that he likes her. When you’re feelings are so genuine it’s hard to keep them concealed.

The movie feels need to make it into a love triangle as Miranda resigns to dance with Kyle and settle in a sense. But James is the mercurial artist with a caddish, manipulating charisma. He’s good with the lines to feed her even as he’s good with lyrics to sing in front of an audience and record deals he’s trying to finagle his way into.

There’s no continuity to him, and yet it’s hard to judge his intentions because even with mixed signals, he does seem to be drawn to Miranda. In one scene in the studio, he mostly ignores her and then in the heat of his performance, he pulls her onstage for an impromptu duet in front of the audience. He even takes her to a drive-in screening of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and they write a song together. I suppose the rivalry between John Wayne and James Stewart for the affections of Vera Miles is a Hollywoodized version of our story.

Their trajectory is exemplified by wanderlust and spontaneity. James pulls Miranda away from her new gig waiting tables at the Bluebird so they can make the pilgrimage to pay tribute to the King. They must hold the title for one of the most unconventional wedding ceremonies as they get hitched in a Memphis supermarket, dancing the night away as the rain comes pouring down outside. It’s life without consequence.

However, cohabitation as a married couple is fraught with conflict. They weren’t meant to live this way with their personal dreams pulling them apart, and their marital expectations far from unified. James’s capricious tendencies reassert themselves, and Miranda feels defeated.

In the wake of an argument, she seems all but prepared to leave her dreams behind. She quits her job and hops on a bus back home only to turn right back around with one last mission to accomplish. She holds up in a cafe to pen her latest song, and as anyone who’s tried to conjure the creative muse knows, some ethereal inspiration just comes to her. Out of nothing something is born fully formed.

She plays her song, singing lucid and tender, all colored by her newfound heartache and experience. It’s not for anyone else, only an audience of one, and yet it’s through this creative paradox her songs finally discover an audience.

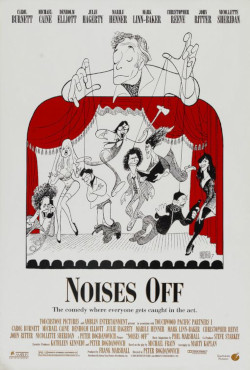

One of the movie’s most agreeable assets is Sandra Bullock who was still on the way up with Speed and While You Were Sleeping in her near future. She’s not immediately identifiable as a loquacious southern belle — it’s not what we immediately attribute to her persona — but it’s easy enough to like her candor.

And if Linda Lue Linden is a foil for Miranda, then Dermot Mulroney’s portrayal of Kyle fits opposite River Phoenix coming to represent not only a physical juxtaposition but a philosophical one as well. What holds them together is a love of country music even as their friendship is now complicated with the suggested ambiguity of a ménage a trois. Not everything is resolved.

Nashville will always be the ultimate film about the country music industry for how wide-ranging, pointed, and tender a portrait it is in the hands of Robert Altman. I won’t even feign a comparison with The Thing Called Love because it is a movie for a new generation reaching out to realize their dreams. And while it paints in this tangible atmosphere of southern twang and steel guitar, it’s best as a story of close-knit relationship.

I’m not sure if anyone would call me a staunch champion of Peter Bogdanovich’s films. I do like them a lot, and it does feel like a handful of them got a bad rap through faulty marketing and unfortunate circumstances. If They All Laughed was marred by the Dorothy Stratten tragedy, then, The Thing Called Love carries the specters of River Phoenix’s untimely death.

He was in the company of his siblings, his girlfriend Samantha Mathis, at the club partially owned by Johnny Depp, as they performed some of his songs together. It seems like such an ill-fated conclusion. This isn’t the way life is supposed to end. For fans of River Phoenix, The Thing Called Love stands as a final testament to his talents, and it’s an unmitigated pleasure to see his passions for music and acting blended together. If the movie’s not his best, then it’s still a fine way to remember him.

3.5/5 Stars

With the name of Orson Welles comes any number of conflicting connotations not far removed from his greatest achievement: Citizen Kane. However, if we had to try and pinpoint an apt superlative it would fall somewhere in between a mythic and Brobdingnagian titan of cinema. He was a personality like few others.

With the name of Orson Welles comes any number of conflicting connotations not far removed from his greatest achievement: Citizen Kane. However, if we had to try and pinpoint an apt superlative it would fall somewhere in between a mythic and Brobdingnagian titan of cinema. He was a personality like few others.