I must have learned about Ritchie Valens through Don McLean’s “American Pie.” Because there was a time when I was fascinated by all the musical references that seemed so oblique to my young mind. Eventually, the songwriter’s ode leads you to “The Day The Music Died” and if you know about Buddy Holly, you soon learn about The Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens.

I must have learned about Ritchie Valens through Don McLean’s “American Pie.” Because there was a time when I was fascinated by all the musical references that seemed so oblique to my young mind. Eventually, the songwriter’s ode leads you to “The Day The Music Died” and if you know about Buddy Holly, you soon learn about The Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens.

The song “La Bamba” feels like a definitive track of a certain rock n roll era, and only now does it become easier to realize what an important cultural milestone it represents. The Mexican language went mainstream blending the rock craze with folk traditions of a people who felt well nigh invisible if no less important in the ’50s.

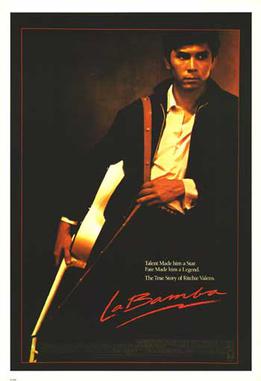

I do not know much about Luis Valdez, but as an emblematic figure in the Chicano movement of the ’60s and ’70s, he also gave us two of the most noteworthy Chicano movies of the 1980s. He turned his own play into Zoot Suit with Edward James Olmos, a film I was never able to fully connect with, but La Bamba feels like a more straight down-the-line biopic. He effectively brings to life one of the great Chicano heroes of the second half of the 20th century.

Lou Diamond Phillip’s vibrant performance glows with undeniable warmth and vitality. There’s not a disingenuous bone in his body, and he’s able to evoke the joy behind the microphone and the quiet fortitude that comes with his humble migrant background.

This is one of the most moving things about Valdez’s film because even almost 40 years on, these slices of life are still not always prevalent on the big screen. To see them in a period piece seems even more fitting because it’s a way of capturing the cultural moment for us lest we forget.

We see the plight and humble living conditions of migrant workers, there’s instability and broken families, but also the unbreakable bonds of extended families and communities looking out for one another.

La Bamba also has many of the beats of the biopic and since I don’t know the life of Valens intimately, I can only give conjecture on what’s fact and fiction. Part of the story involves his older half-brother (Esai Morales), who exists as the black sheep of the family opposite Ritchie. There’s the blooming of young love with the new girl in class, Donna (Danielle von Zerneck). His family and high school lives run in tandem with his meteoric rise after a record producer, Bob Keane (Joe Pantoliano), agrees to record some of his tracks.

Valens fear of flying, after a midair collision over his school, which killed his childhood friend and left him with recurring nightmares, has the ring of truth stranger than fiction. In keeping with this, the opening interlude of Santo and Johnny’s “Sleepwalk” feels apropos to represent the general mood of the era. What follows is a bit of a dream even as other moments sting with harsh realism.

There are so many narratives that could happen. There’s a bit of a Romeo and Juliet romance as Donna’s father tries to rebuff Ritchie’s sincere advances. Still, Donna remains devoted throughout the picture, and what a lovely thing is to see their euphoric joy together. The images suggest you don’t have to look like one another to fall in love. The fact the movie draws up this star-crossed romance between a 17-year-old and his 15-year-old beau feels of small consideration. It is a movie.

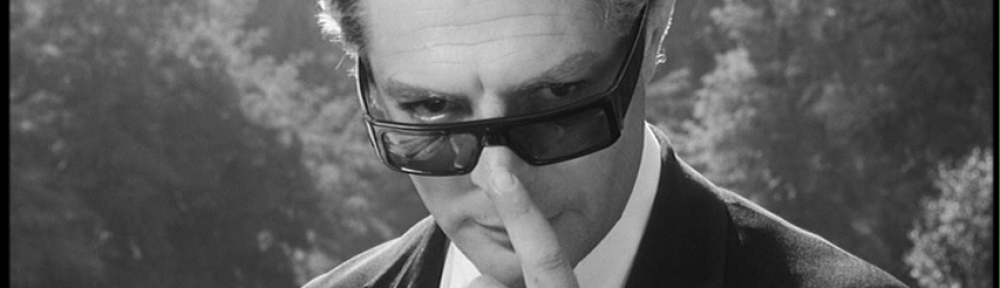

His brother knows how to make an entrance rolling up on his motorcycle, sunglasses on, cigarette between his lips. Or maybe this is only how we imagine him. Still, Bob’s demons could have been their own movie making him into a perturbing, abusive, drunken figure at the movie’s volatile center.

He’s effectively cast as Cain, never good enough or able to find favor in comparison to his thriving little brother. He spends the whole movie self-destructing and coming to terms with his brother’s burgeoning success. Later in life, it seems his real counterpart was able to resurrect his life and became a beloved member of his community.

Likewise, Bob Keane shows up in Ritchie’s life. We don’t really know how he got there or what all his motives are; still, there’s nothing too sinister in it. He helps Ritchie get big by recording and promoting him, and Valens is on top of the world.

It’s easy to see how all of these dynamics might have been either simplified or drawn up in such a way as to streamline the story or punctuate the dramatics. And yet I never begrudge the movie its choices, because it does feel like such a bountiful cultural artifact. The fact Los Lobos provided much of the soundtrack and even show up in a musical cameo is another notable distinction.

And the gutting, sinking feeling in the pit of our stomachs signals the dream cannot last. This talent taking the world by storm and rocking out with Eddie Cochran and Jackie Wilson will be snuffed out far too soon. So if everything else gets resolved in a Hollywood manner, our star is still going to be taken from us in the final reel. There’s no way to get around it.

McLean’s song mourned over it as “The Day The Music Died.” Thankfully, he was wrong. Yes, we no doubt lost out on years of musical output from Holly and Valens. Their young talents were undeniable, and yet their contributions to rock ‘n roll are far from dead. For their relatively short time in the public eye, they’ve cast very large shadows indeed. “La Bamba,” “Come on, Let’s Go,” and “Donna” feel like genre standards by now.

In his own way Valdez has guaranteed Valens won’t be totally disregarded (it was added to the National Film Registry in 2017), and Lou Diamond Phillips, bless his heart, made Valens far more than a hagiography of a deceased icon. He’s a young man with a warm, beating heart, a love for his family’s culture, and a love for rock ‘n roll. I can’t think of a better testament to Ritchie Valens than that.

4/5 Stars