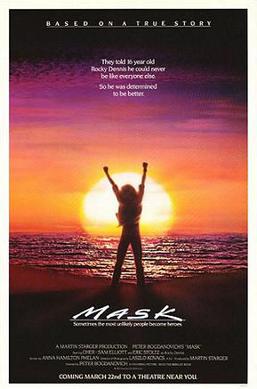

Peter Bogdanovich lost his girlfriend Dorothy Stratten to tragedy in 1981 and after the release of their picture together, They All Laughed, it was anyone’s guess if he’d ever be able to return to directing.

I’ve heard an often-repeated anecdote that he ultimately decided to take Mask as his next project as a way to honor Dorothy. The reason isn’t immediately obvious. However, he explains that Dorothy was fascinated by the Elephant Man, who shared the same condition as Rocky in Mask. But she was a highly sought after beautiful woman. How could she relate?

It seems that extreme ugliness and extreme beauty by the world’s standards puts you outside of the normal purview of society. It’s not something individuals asked for. They are born with it or given it by circumstance, and as a result you have the world’s prying eyes looking at you. So both of these films are about this kind of social “others,” who must make an existence for themselves in a world where they’ll never quite fit in.

The greatest epiphany of Mask is how Rocky (Eric Stoltz) does exactly that. We’ve seen movies about people lashing out because of the hand they’ve been dealt. This is a reasonable reaction, but this movie is never about that.

It’s my own human inadequacies making it so I look at him and feel discomfort. But it’s a classic example of not judging a book by its cover. Outward appearance doesn’t define the mark of an individual.

The brilliance of this teenager is how he rewrites the script and subverts the expectations around him. He’s the personification of all our outcast inclinations when we’re in middle school and high school. None of us would have envied him during those formative years. And yet he rarely gets rattled by any of it, even when he might have the most excuse to do so.

Rocky has a level of supreme confidence so in a manner of weeks teachers know he can succeed and look after himself and his fellow students come to appreciate his wit and his near-Encyclopedic knowledge. He has a high view of himself and this allows him to be self-deprecating. I like the idea that we don’t think less of ourselves, but we think of ourselves less often. It makes our lives centered around others.

Part of this is the family unity around him. They support him and love him for who he is even as he does yeoman’s work to look after his mother. It’s almost as if he’s her guardian sometimes with the lifestyle she leads, a holdover from the ’60s with drugs and a conveyor belt of male suitors.

Cher is a powerful force and she always has a natural charisma in front of the camera that suggests so much about her. Although their relationship is the backbone of the whole movie, they have an entire motorcycle gang to watch out for them including the old family friend and Cher’s past lover Sam Elliot.

He’s a quiet enigma of cool, but with his laidback demeanor and a “Moustache Rides” tee, a character who could easily be a vehicle for outside conflict becomes more of a stabilizing force.

Rocky is even granted one of the loveliest adolescent romances of the 80s as he begrudgingly decides to spend his summer volunteering at a camp for the blind meeting Diana Adams (Laura Dern).

It’s reminiscent of City Lights with a love story based on personality and kindness as opposed to superficial appearance. In other words, it is a deeper bond and even as she’s an equestrian girl with an affluent background and he’s been raised on the road with a motorcycle gang, they relate on what’s most important.

I couldn’t help myself and seek out the writing on the wall. Rocky can’t last forever. In real life Roy L. “Rocky” Dennis passed away at 16 years old. If you didn’t know him you might think this was merciful and yet having watched his life play out on screen, we see the tragedy of it. He was such a loving, vibrant, jovial force to behold. He could have accomplished so much. And one can only imagine his mother was devastated. Because her boy was special and the bond they held was incomparable.

Bogdanovich augments the story with his trademark use of dietetic sound to fill out the world on top of some of Bruce Springsteen’s finest tracks. I watched the director’s cut which included a few extra scenes and all I can say is that I’m thankful to Bogdanovich’s conviction to get his version out there without compromise. This included working with Springsteen himself to get the original recordings licensed for the rerelease. It pays heavy dividends.

Regardless of the director’s shortcomings, I will dearly miss his classical sensibilities as a filmmaker. He made films imbued with joy and melancholy. Both speak to me and surely I’m not the only one because life becomes a subtle dance between a panoply of emotions.

Like the masters of old, he was able to take a story and personalize it so the core themes are somehow made manifest and evident in his own life. It’s a lovely brand of storytelling, and it allows Mask to constantly ambush us with some winsome surprises. This is how movies should be.

4/5 Stars

Francois Truffaut has a knack for understanding children in all their intricacies. One suspects it’s because he’s never really grown up himself. He is a child at heart with even his earliest films of the Nouvelle Vague channeling the joy and the passion of a younger individual.

Francois Truffaut has a knack for understanding children in all their intricacies. One suspects it’s because he’s never really grown up himself. He is a child at heart with even his earliest films of the Nouvelle Vague channeling the joy and the passion of a younger individual.