The western is founded on certain unifying archetypes, from drifters to revenge stories, showdowns and the westward progress of civilization butting up against the lawless wilderness. It always proved a fitting genre for morality plays and deeply thematic ideas. The tradition of the bank robbery goes back to Edwin S. Porter and The Great Train Robbery, and it plays an important role in The Naked Dawn.

The western is founded on certain unifying archetypes, from drifters to revenge stories, showdowns and the westward progress of civilization butting up against the lawless wilderness. It always proved a fitting genre for morality plays and deeply thematic ideas. The tradition of the bank robbery goes back to Edwin S. Porter and The Great Train Robbery, and it plays an important role in The Naked Dawn.

The action opens with Mexican banditos robbing a train and looking to flee the scene. Though they manage to get away, it’s not without consequences. One hombre named Santiago watches as his campanero Vincente dies in his arms. He comforts him with visions of heavenly cattle grounds even though the man’s life was full of indiscretions, to put it nicely.

The story does occupy itself with religious rhetoric, which feels very much a part of the cultural landscape, as do the Spanish language and such ubiquitous elements as taco stands, cantinas, and a mariachi soundtrack. The film rightly steeps itself in this perceived world below the border. Whether it is authentic or not feels slightly immaterial, because something fairly immersive is erected. In one sense, this is the most impressive success of The Naked Dawn.

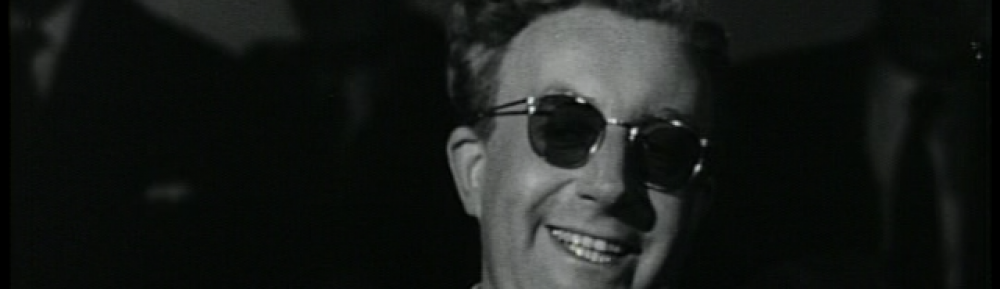

There is “brownface” needing acknowledgment and a certain stereotypical gaze, but director Edgar G. Ulmer develops a surprising amount of atmosphere for such a meager western. Secondly, Arthur Kennedy somehow manages to give a thoroughly flamboyant performance showing his competency in anchoring a leading role — even in an admittedly small scale oater like this.

Because in typical drifter fashion, he goes from leaving his dead buddy behind to finding a day’s shelter at a farmhouse along the trail. There he is met by an energetic young farmer and his dutiful wife. The presence of such a figure as Santiago unearths all their flaws even as he overwhelms them with his vagabond existence, full of a certain high-living and nostalgia for the old days.

Although initially hesitant to get involved, the husband finds himself brought along for a raid on a crooked shipment manager who they overpower and string up while raiding the contents of his safe. In the midst of all the money, Manuel (Eugene Iglesias) suddenly becomes brave and also greed springs to life in his heart.

For thence onward, Manuel holds this stranger in high regard, in awe of this man who has seen so much and takes him for the time of his life in the local watering hole, partaking of all the worldly pleasures afforded from strong drink, saucy women, lively music, and a bar brawl to wind out the entertainment.

But if this is the grand exciting world away from the ranch, then back with his doting wife (Betta St. John), we find a certain amount of unrest. She does not love her husband but his prospects were so much better than what she had before. Still, this new man makes her heart glad; she is ready to elope with him without fear of consequences.

The utter irony is the very fact that while Santiago is the outlaw, at least he is obvious and upfront about his waywardness. In his new company, Manuel fancies himself an honest man and his wife comes across as an angel. However, whether it’s unwitting or not, they both have more conflicted characters than they let on. Santiago is the one who allows them to salvage their lives.

It should be noted Francois Truffaut purportedly gleaned inspiration from this film’s love triangle for Jules et Jim. At first, any sort of comparison seems superficial at best. However, I finally settled on the fact both films contrive this three-way relationship that plays peculiarly for the very fact it lacks a great deal of interpersonal drama.

There is a passivity to how it unwinds and this feels counterintuitive to how these stories are supposed to function. Although we have tragedy on both accounts, the fact it is so detached leaves a different taste, rather than a blistering, jealousy-fueled gunshot finale. For that, we have to look at alternatives like Laura (1944) or Truffaut’s own Soft Skin (1964).

There is not a lot of time and space but the resources are used in all number of facets to at least touch on issues of religion, law and order, romance, greed, and unquestionably, so much more. Fittingly, as the picture zips to its rapid conclusion, we have come full circle with our larger-than-life Bandido dreaming of the pearly gates much like his campanero before him.

Ulmer blesses the audience with another extraordinarily lucid 10-day effort. Let that sink in for a second. The Naked Dawn is yet another marvel in economic ingenuity. Better yet, any drop off in quality or production values only seems to add to the film’s inherent flavor.

3.5/5 Stars