We usually think of filmmakers like Woody Allen or even Noah Baumbach for their portrayals of New York. There’s no doubt they have left their imprint on the city, so it’s difficult not to envision it without their influences. However, in his own right, Sidney Lumet also deserves to be viewed in this light, even if it originates from a fundamentally different perspective.

Lumet is a director who seems to know this place intimately, but he hardly sugarcoats it. He gives us something loose and engaging, full of human drama. We saw it in everything from 12 Angry Men (1957) to Serpico (1973). With Dog Day Afternoon it’s much the same.

The film starts with a boat, before making its way across the city with imagery of both the vocational and leisurely activities of the general populous. People are bumping tunes as these city-wide scenes hum with the familiar rhythms of daily life. It seems a curiously wide net to take from the outset, only to make concrete sense minutes later.

Alongside these typical shots is something highly irregular within this same context: The attempted robbery of a local bank. One can easily champion Dog Day Afternoon as the greatest heist film for the very fact it is a comedy of errors because the sub-genre has always been defined by all hell breaking loose as everything eventually goes awry.

This picture never even gets there. It’s the purest articulation of the core tension flowing through any heist movie, going back to the days of The Asphalt Jungle (1950) or The Killing (1956). However, in this case, we are provided none of the same space for a setup or earlier preparation. It’s all the mechanisms of the job going haywire right in front of our eyes. It’s not even that the perfect plan hits a fateful snag or there’s a turncoat or what have you. These robbers are obviously sunk before they’ve even begun, and the story pivots on this, becoming something novel in itself.

It commences with their youngest accomplice who doesn’t have enough stomach to go through with it, and he literally bales on them during crunch time. Sonny (Al Pacino) and his buddy Sal (John Cazale) muddle through because the gun has already come out. They’re committed to what they’ve started. Soon the manager and female tellers are rounded up along with the security guard. No one’s looking for trouble.

But this is just the beginning. Because when they finally get to the issue at hand — the money in the vaults — there’s barely any cash. It was all taken out in the latest shipment. Strike two.

Though Sonny professes to know the ins and outs of bank work, he’s none too bright and in one of his most gloriously idiotic blunderings, he burns up the bank’s register only for the smoke from the wastebasket piquing attention out on the street. Just about everyone needs to use the toilet; they’re the kind of complications you don’t usally make allowances for in such a scenario.

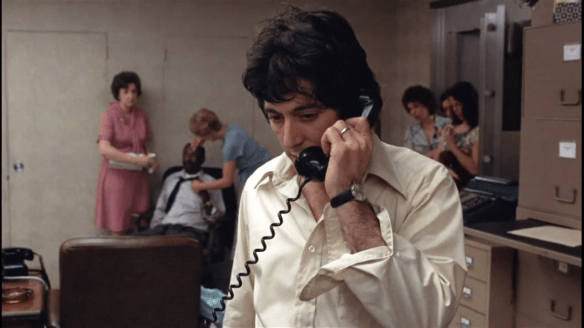

Meanwhile, the police swarm the sight and Sergeant Eugene Moretti (Charles Durning) takes on the point to strike up a line of communication with the criminals. This is phase two where Dog Day evolves into a story where the aftermath of this event takes the most prominent place but for altogether different reasons than we usually expect. We reach this point of extended stalemate.

The security guard is plagued by asthma and gets sent as a sign of good faith, but Sonny’s not about to take any double talk. In the galvanizing moment that forever vaulted Dog Day Afternoon into the conversation of anti-establishment cinema, Pacino walks out on the streets and dares the cops to back down.

This is his stand, and it catalyzes the rest of the film’s action. He knows he has power because the crowds are watching him — if not the entire city. In a moment of inspiration, he starts screaming “Attica” and as his chants, evoking the contemporary prison riots, sweep through the onlookers, and they begin to cheer him on almost as if he’s one of their heroes, and he has found solidarity with them.

TV coverage makes everything live and visible to the viewing public, and it’s the same game we can play with Network (1976). If the media was invasive back then, just imagine how much more of a parasite it is now with smartphones capable of capturing everything.

One might say Dog Day Afternoon documents a very specific cultural moment because we have only continued to progress from there with the media getting more and more intrusive as time goes on.

This strange almost absurd strain of insanity becomes acceptable. Where we have stalemates and compromises with people trying to communicate and defuse a situation of the most volatile nature. All because of a measly bank robbery running afoul.

The drama settles into a strange equilibrium where everyone is trying to work with everyone else to get out of the current situation. The captors and their captives on the inside form a rapport over time. A type of Stockholm Syndrome sets in. Then you have the uneasy symbiosis of the perpetrators and the cop on the outside looking to defuse the situation so the hostages get away safely.

It’s a shortlived truce blowing up again when someone tries to sneak into the back and a shot goes off, sending the police and crowds into a frenzy. On the inside, it isn’t much better. Pacino is at his most intense following up the slow burn of the Godfather Part II (1974) with something equally grating. It’s not exactly documentary, but there is a certain sensibility to it that makes it continuously tense and strangely funny, in its most organic moments.

It only falters with its substantial length, because after losing some of its tautness as an out-and-out thriller, it falls into the strangely comically strains of theatrics before getting distracted by any number of things. These are the lulls that are weathered by the sheer ferocity of Pacino’s performance.

There’s the complication of paying for t the sex change operation of his partner. His mother comes to the scene of the crime to coax him to give up, and it’s another distraction he could do without, in between the phone calls he’s constantly fielding with the police.

In his semi-delusional mind, he develops grand plans to get a car to take them to the airfield where they’ll head to Algeria. Sal is menacing but generally composed, played with matter-of-fact sentience by John Cazale. You almost forget he’s there. The only moment he seems obviously perturbed is when the news outlets make out that he’s gay. He wants Sonny to set them straight.

At the center of this insanity, sweating it out and trying to balance all the pressures thrust upon him is the man himself. He orchestrated this whole thing only for it to blow up into a local phenomenon he could hardly control. He becomes the ringleader of his own form of media circus — albeit on the inside — on par with anything whipped up by Kirk Douglas in Billy Wilder’s Ace in The Hole (1951).

The ending wallops equally hard like cold air hitting the face. Again, we met with this weird sense of total equilibrium restored. Life can settle back into normalcy. It’s simultaneously a welcome sigh of relief and still a hollow victory.

Because even if it was momentary, we were in Sonny’s corner too — right there with his hostages — and maybe after spending so much time with him, we were inflicted with a bit of Stockholm Syndrome ourselves. There is this wishful hope that he just might get away and things could turn out. In this austere, pragmatic world of ours, such sentiment seems like folly.

Lumet documents the milieu while Pacino captures its ensuing despondency with his usual unflinching fury. At its best, Dog Day Afternoons is driven by performance, and its director creates an impeccable world for incubation.

4/5 Stars