I know only very little about River Phoenix’s upbringing but somehow it’s easy for me to make the leap from his real-life existence to his family in this movie. Running on Empty has to do with an unconventional upbringing.

Danny Pope (that’s his real name) has grown up with his little brother and two parents Annie (Christine Lahti) and Arthur (Judd Hirsch), who have lived on the run from the feds since the early 70s. They were implicated in an anti-war protest at a napalm plant that left a janitor dead.

The Popes are a tight-night clan in spite of their unusual circumstances or because of them. Somehow in this environment of constant flux and fresh identities, they’ve managed to raise two boys who are loving and smart.

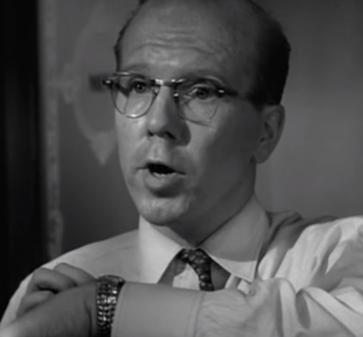

Danny enrolls in a new school and immediately distinguishes himself on the piano. He seems like an obscure prodigy because no one knows anything about him and his benevolent music instructor (Ed Crowley) gets little information on him. Still, he’s talented and generally considerate. He doesn’t play into the expected stereotypes of a malcontent.

He also meets the acquaintance of the teacher’s daughter (Martha Plimpton) who has a much more jaundiced view of education and musical appreciation. She’s used to a more typical lifestyle and yet she’s drawn to the new boy not out of an act of rebellion against an overbearing father or anything like that. Danny is genuinely decent and kind. She immediately likes him, and they spend time together. She wants to get to know his family too and so she does.

I was a bit disappointed Jackson Browne’s tune “Running on Empty” has no place in the movie, but they may have done themselves one better with James Taylor’s “Fire and Rain.” Their celebration of Anne’s birthday turns into a dance party in the dining room; there’s something spontaneous and joyous about it.

It encapsulates the best aspects of the movie where we’re suspended in these moments of relational goodness. To be a part of the scene feels organic and the characters become all the more real in front of our eyes. We enjoy their company.

Martha Plimpton has a James Dean Rebel Without a Cause poster in her bedroom and somehow Phoenix carries some of the same ethos. There’s the morbid similarity in that they both died young and yet more than that, it has to do with a palpable emotional investment in their roles. It’s more like music than it is blue collar craftsmanship and their brand of sensitive masculinity feels off the charts.

Phoenix has an emotional maturity and precociousness that feels wise beyond his years and still wracked with inner demons. Here he must carry the burden of his parents’ life. It also fuels the budding romance that Phoenix and Plimpton were an item in real-life.

Christine Lathi still feels mostly underappreciated as an actress. She’s a loving mother, a strong wife, and the scene where she has a teary reunion with her father after many years is lachrymose but never totally saccharine. They supply just the right amount of heartbreak and tenderness.

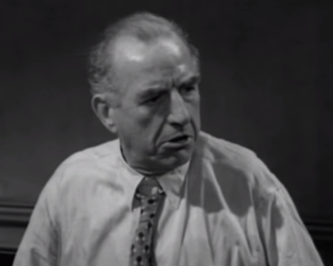

Judd Hirsch deserves his plaudits as well though if you’re like me you appreciate him for being the stabilizing force on Taxi. He plays the part so well that sometimes you forget he’s an actor’s actor.

I’m reminded of his rapport with Timothy Hutton in Ordinary People and his scenes with Lahti and Phoenix here. He always gives off this aura of street smarts. He’s tough and able to spar, but it’s never totally untethered from his unerring heart. He cares and somehow he’s able to make his audience feel his concern.

What I appreciated most is that Running on Empty never feels over reliant on its political elements which are often relegated to the background in favor of far more sensitive developments of character. It would be so easy to succumb to drama. Instead, it chooses a more nuanced road as Danny starts to put down roots and gets encouraged to apply to Julliard. Suddenly, his lifelong anonymity is bumping up against his youthful dreams of a normal future.

Director Sidney Lumet was always a fine filmmaker and one of the most enduring because he was a workman and he knew how to rehearse, he was smart, and made compelling movies. Running on Empty is never one of the most high profile mentioned but it leaves space and feels attuned to the family at its center and the relationships. This is why I go to the movies to be shown people’s humanity up on the screen and then be uplifted by it.

The movie hardly dwells on its ending. Perhaps we could have done with a bit more resolution, but it does itself proud with a refrain of James Taylor’s “Fire and Rain” pulled from the earlier scene. It’s as if the chorus of singing voices — the family all joyful and gay — is a concrete reminder that that bond will never be broken even as they move on. There’s something satisfying about discretely reaching back and referring to the movie’s most poignant moment. Because it means so much and these are the kind of memories we carry with us wherever we go. Family is forever.

4/5 Stars

been offered. But honest help is hard to find especially from someone who makes it stick. The higher ups care more about the reputation of the department over corruption, making progress difficult to come by. He continually bounces around from division to division and nobody seems to want him, or trust him for that matter. There are only a few honest Joes around and they are few and far between. Serpico gets transferred this time to the “upright” 7th division and begins seeing his next door neighbor named Laurie. Too soon he learns that one of his acquaintances is instrumental in the extortion that takes place department-wide. By now Frank is feared, hated, and despised because he will not take money under any circumstances. It takes its toll to be all alone in the force, and he lashes out at Laurie who leaves him for good. Now he truly is alone.

been offered. But honest help is hard to find especially from someone who makes it stick. The higher ups care more about the reputation of the department over corruption, making progress difficult to come by. He continually bounces around from division to division and nobody seems to want him, or trust him for that matter. There are only a few honest Joes around and they are few and far between. Serpico gets transferred this time to the “upright” 7th division and begins seeing his next door neighbor named Laurie. Too soon he learns that one of his acquaintances is instrumental in the extortion that takes place department-wide. By now Frank is feared, hated, and despised because he will not take money under any circumstances. It takes its toll to be all alone in the force, and he lashes out at Laurie who leaves him for good. Now he truly is alone.