The first time I ever saw The Woman in The Window it always struck me as odd. Here was the fellow who was known as a gangster through and through and yet he was playing a bookish professor buried in his work and obsessed about psychoanalytic theory. His idea for a fine time is conversing with his intellectual friends (Raymond Massey and Edmund Breon) at the Stork Club. He’s the epitome of middle-aged solidity and stodginess as he so aptly puts it.

But in confronting these very things, you realize Robinson might have enjoyed any opportunity to get away from what everybody seemed to peg him as — to exercise a certain amount of elasticity as an actor — to be the antithesis of his image. This is all mere conjecture, mind you, because as the story progresses, you realize the character is a bit mundane.

Regardless, veteran Hollywood screenwriter Nunnally Johnson spins a story of psychological intrigue as his first showcase for his newly founded production firm International Pictures. This Fritz Lang effort along with a handful of others would instigate the stylistic categorization of “film noir” by French critics in the post-war years. There’s little doubt it fits many of the fluid conventions of noir. Though overshadowed by the even more sinister Scarlet Street from the following year, it is a genre classic in its own right.

As alluded to already, it’s also steeped in psychology. In fact, it gets knee deep in it from the opening moments in such a fashion that we know it will remain all but integral for the entire run of the narrative. Professor Wanley is enraptured by an image, a portrait of a woman to be exact, and it elicits the same spell Gene Tierney would have in Preminger’s Laura (1944). But of course, it is the woman being animated for real that brings true life to the movie and it’s no different here.

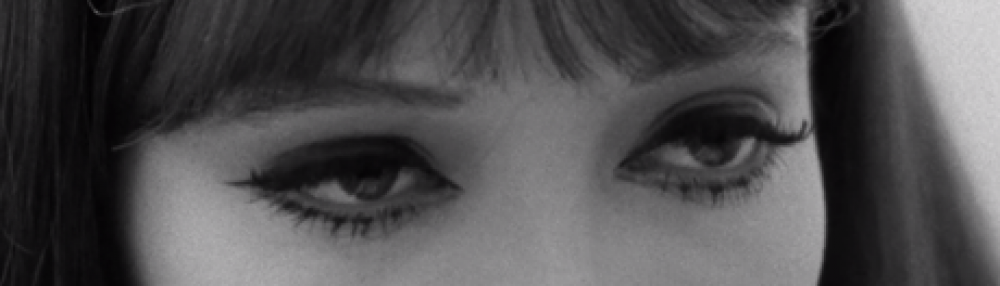

This brings us to the part that’s actually the most gratifying and probably would have been the most enjoyable to play. That of the eponymous woman staring back through the window. Joan Bennet is positively bewitching and grouped with Scarlet Street (1945), it remains some of the defining work of her career, which is hardly something to be dismissive of.

As best as it can be described, she has a pair of those coaxing, inviting eyes. Bennett, to a degree, seems to play up her Hedy Lamarr appeal with jet black hair but her looks are her own as is the spellbinding performance and it works wonders starting with the man on the screen opposite her.

He foregoes a burlesque show to engage in some “light” after dinner reading of Song of Songs. Though he’s probably looking at it from a purely academic perspective, one can gather that between his psychological theories and the fairly explicit poeticism of his reading, he’s got quite the cocktail brewing in his mind.

He gives the portrait another look as he’s about to head home, as is his normal tendency. In this particular instance, the woman is present in the flesh and they share some complimentary words. That leads to drinks and then a venture to her apartment to wind down the evening perfectly innocently.

However, instantly his life is transformed into a living nightmare as they are interrupted by a scorned boyfriend with a horrid temper going at Richard who has no recourse but to strike his adversary down in a frantic attempt at preserving his own life. It was self-defense but the damage has been done and the results are not-so-conveniently lying on Ms. Reed’s carpet.

Even with these turn of events, the professor takes them in stride, systematically and semi-rationally coming to a decision that while risky just might be the most beneficial plan of action, at least in theory. There is much that needs to be done. He enlists Alice to clean up the crime scene by both getting rid of blood and incriminating fingerprints. Any evidence that would implicate either of them must be done away with methodically.

He puts it upon himself to dispose of the body, which is no small task as the dead man has a massive frame. It takes up a lot of space and causes him some grief. He gets rid of it but not without incurring a cut and a rash of poison ivy while also leaving behind some clues that indubitably will have a bearing on the case.

However, he also has the rare privilege of being so close to the district attorney and the head of the homicide department to see first hand how they’re getting on with the case. If anything it unnerves him more assuming he will soon incriminate himself with a minor slip of the tongue or worse yet be found out in his clandestine activities due to the thorough investigation underway.

Dan Duryea has a small-time role playing what he was best at, a sleazy enforcer looking for blackmail or any other dishonest way to make a buck. Thankfully his part would be expanded upon in Scarlet Street as he came back for a second helping. His career is composed of an interesting trajectory even earning him a few starring spots in his later efforts like Black Angel. He’s an underrated talent who made classic Hollywood and noir in particular that much more engaging. One could wager it’s Bennett and Duryea who really clean up shop as they would do again the following year.

To mollify the production codes, Fritz Lang settled with the ultimate cop-out ending. While it would normally disgruntle me, the sheer lunacy of it all and the fact the picture is so embroiled with themes of the human psyche makes it marginally okay. If anything, the fact there was a superior followup the next year takes the sting out of it. Still, there’s no downplaying that Woman in The Window was crucial in laying the groundwork of what we now consider film noir, complete with murder, femme fatales, fatalistic heroes, and shadowy extremes courtesy of cinematographer Milton Krasner. What’s not to love? It’s certainly worthy of a second dose.

4/5 Stars

Your last paragraph may have changed my mind about that ending. And I completely agree that the superior Scarlet Street the following year makes up for it. I wrote about them on my blog a few years ago, time to watch them again!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! My review of Scarlet Street should be out shortly. I completely understand people not liking the ending. I’m marginally okay with it because it somehow fits Robinson’s character for me.

LikeLike

I couldn’t help but notice, when watching this film, how Joan Bennett is wearing some sort of gauzy see-through top that leaves her breasts completely visible, throughout the whole scene that ends with her sugar daddy getting killed. Shocking that got past the censors in 1944.

Lang said in an interview once that the ending was his idea and not an imposition from the Hays Office.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not visible but the illusion of it.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Locket (1946): Laraine Day and Splintering Psychology | 4 Star Films