Gigi (1958)

Lerner & Loewe’s adaptation of Colette’s Gigi is a picture accentuating the France of Hollywood’s most opulent dreams and confections frequented by the consummate French people of the movies: Maurice Chevalier, Leslie Caron, and Louis Jordan.

Whether it’s Ernst Lubitsch or Billy Wilder or Vicente Minnelli, Chevalier doesn’t change much. He’s convivial with the audience existing just on the other side of the camera. He gives off his usual cheeky, harmless charm that doesn’t always play the best seeing as his first tune is about the litters of girls who will grow up to be married and unmarried young women in the future.

Gigi (Caron) is one of their ilk, a carefree gamine who lives under the auspices of her Grandmama’s house, a startling domicile touched by Minnelli’s charmed palette of deep red.

In some manner, Gigi seems to represent the worst of Minnelli. Yes, it was wildly popular in its day, but all of its manicured embellishment and immaculate set dressings feel mostly fatuous and merely for their own sake. While one can easily appreciate the pure spectacle of the thing, the director’s best pictures show a deep affection for characters.

Here all manner of songs and tête-à-têtes are cheery and bright, while never amounting to something more substantive. It’s easy to suggest the movie revels in its own frivolity. Gaston (Jordan) is a ridiculously wealthy young man and Eva Gabor is his companion, though the gossips get ahold of them. They’re not in love.

Another primary reservation with the picture is how Leslie Caron is summarily stripped of most of her powers. At times, dubbing feels like an accepted evil of these studio-era musicals or a stylistic choice of European maestros. However, in Caron’s case, not only is she not allowed to sing, she can’t talk for herself either (dubbed by the cutesy Betty Wand). I might be missing something, but this seems like a grave misfortune.

You can add to this fact the further grievance she never really has a traditional dance routine, and there’s nothing that can be appreciated about the picture in comparison to the crowning achievements of An American in Paris. All that’s left is to admire is her posture and how she traipses across the canvasses Minnelli has devised for the picture. This alone is hers to control, and she just about makes it enough.

My favorite scene was relatively simple. Gigi and Gaston are at the table playing cards, and they exude a free-and-easy camaraderie. If it’s love, then it’s more like brother and sister or fast friends who like to tease one another. It isn’t yet treacly with romance. Instead, they break out into a rousing rendition of “The Night They Invented Champagne,” which distills its point through an exuberant melody.

The lingering power of the film is how it does its work and grows on me over time. It considers this not totally original idea of trying to become who you are not in order to please others. Gigi must learn the breeding and the etiquette, acquire the clothes, and in short, turn herself inside out in order to fit into rarefied society.

Gaston doesn’t want her to be like that, attempting to replace all the elements of her character that make her who she is. This is what he likes about her. If it never turns to eros, then at the very least, it’s shared affection. Caron and Jordan make their auspicious entrance at Maxim’s and, it feels like a precursor to Audrey Hepburn’s introduction in My Fair Lady. It’s not a bad comparison since most of the film is filtered through speak-singing.

Does it have a happy ending? In a word, yes, but Chevalier singing about little girls doesn’t make me any less squeamish the second go around. Thankfully, Minnelli is no less of a technical master with Gigi. Still, film was not meant to live on formalistic techniques alone.

3/5 Stars

Bells Are Ringing (1960)

The title credits are so gay and cheery with so many admirable names flashing by on the screen, it almost negates the sorry realization that this is the last go-around for the famed Arthur Freed Unit at MGM. Pick out any of the names and there’s a history.

Say Adolph Green or Betty Comden for instance; they were the architects of some of the era’s finest. Anyone for Singin’ in the Rain or The Band Wagon? The movie spells the end of the era, though there would be a few later holdouts.

Like It’s Always Fair Weather, Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, or Pillow Talk, Bells Are Ringing is well aware of its cultural moment, and so it reminds us about the necessity of telephone answering services. Actually, one in particular called Susanswerphone.

It’s easy to love Judy Holliday from the outset as she’s playing crazy gymnastics on the telephone lines because automation hasn’t been created yet. Originally, she was a comedienne best remembered for a squeaky voice and a ditsy brain. Bells Are Ringing, which she originated on the stage, allows us to see a different contour of her movie personality, one that might as well hewn closer to the real person.

She does her work ably only to suffer through a dinner date from hell (with her real-life boyfriend Gerry Mulligan). However, we couldn’t have a movie without a dramatic situation.

The staff are forewarned never to cross the line to “service” their clients. But she breaks the cardinal rule, overstepping the bounds of a passive telephone operator and becoming invested in the lives of those people she communicates with over the wires. Not least among them, one Jeffrey Moss (Dean Martin).

She’s just about lovesick over his voice. It’s no mistake that she puts on her lipstick before ringing him up to remind him about a pressing engagement, as if he can take in her appearance intravenously. Alexander Graham Bell never quite figured out the science behind that.

It’s not much of a mystery to us what Moss looks like. Because if you read the marquee, you know it’s Dino. But she doesn’t know that and scampers up to his room to save him. Surely there’s a Greek tragedy trapped in here somewhere. If it’s not about falling in love with a reflection or her own work of art, then it’s about the sound of a man’s voice. She wants to help him gain confidence in his own abilities as a writer.

But first please allow me one self-indulgent aside. Dean Martin had a point in unhitching himself from Jerry Lewis. Sure, Lewis had a groundbreaking career as an actor-director, but Dino was so much more than The Rat Pack and his TV program.

The string of movies he took on throughout the 50s and 60s never ceases to intrigue me. He could go from The Young Lions, Some Came Running, and Rio Bravo to pictures like Bells Are Ringing and Kiss Me Stupid. For someone with such a distinct professional image, he managed a steady array of parts.

The number “Just in Time” in the park is made by Holliday in striking red and Dino crooning through the night air. There’s a goofy brand of showmanship between them that we were lucky to see in many of the old MGM pictures. It’s their own rendition to complement Astaire and Charisse from Band Wagon showcasing Minnelli at his best and brightest as we are brought into a moment of fluid inspiration where all facets of the production look to be working on high cylinders.

At the nearby party, Holliday becomes overwhelmed by the Hollywood glamour scene, as all the folks jump out of the woodwork and start smooching as Martin descends down a spiral staircase. This only happens in the movies, and yet it’s a summation of her blatant otherness. She doesn’t fit in this crowd where everyone is on first name basis with the biggest names in the business (“Drop That Name”). It seems like their worlds are slowly drifting apart as her secret life is about to totally unravel.

However, Martin joins forces with a musical dentist and Mr. impressionist himself, Frank Gorshin, who puts on his best Brando impression as they bring the movie to a striking conclusion. The same woman has changed all their lives for the better. Now they want tot return the favor. Moral of the story, get yourself an answering service, especially one with someone who cares like Judy Holliday.

3.5/5 Stars

Two Weeks in Another Town (1962)

It might play as unwanted hyperbole, but when I look at Two Weeks in Another Town, it almost feels like a generational predecessor to Heaven’s Gate. Although Vincente Minnelli’s picture is well aware of the old hat and the emerging trends of cinema, it’s raging against the dying of the light, as it were. He subsequently bombed at the box office, and we witnessed the cinematic death knell of an era.

The director makes the transition from b&w to color well enough as you would expect nothing less from him. Kirk Douglas has what feels like a standard-issue role seething with rage thanks to a career hitting the skids. He’s bailed out of his sanitarium by a collaborator from the old days and shipped on-location to Rome.

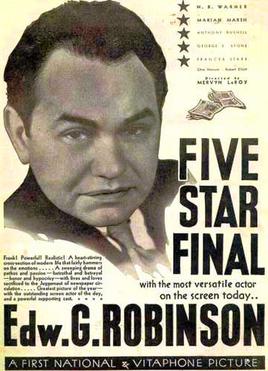

There we get our first taste of a demonstrative Edward G. Robinson playing the tyrannical old cuss Maurice Kruger. He’s right off the set of the latest Cinecitta Studios big screen epic with George Hamilton, an Italian screen goddess, and Vito Scotti working the action.

But Two Weeks in Another Country is just as much about what is going on behind the scenes of the production. Robinson and Claire Trevor together again have a far from congenial reunion after Key Largo generations before. They’re part of Hollywood’s fading classes, though they’re far from relics.

Minnelli takes the personal nature of the material a step further. In a screening room watching The Bad and The Beautiful, the self-reflexivity has come full tilt as Douglas wrestles with his image onscreen from a decade before.

Meanwhile, Cyd Charisse makes her entrance on a jam-packed road flaunting herself in the traffic. She’s charged with playing Carlotta — Jack’s former wife — she’s bad and if her turn in Singin’ in the Rain is any indication, she’s fairly accomplished in this department. It’s almost a novelty role because she’s rarely the focus of the drama, only a sordid accent.

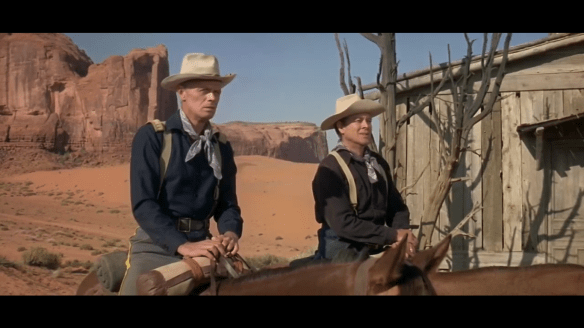

The pieces are there for a truly enrapturing experience as only the olden days of Hollywood can offer. I’m thinking of the days of Roman Holiday, sword and sandal epics, and La Dolce Vita. The movie is a reaction to all of them in the flourishing TV age with its glossy romance in beautiful cars, glorious rotundas, and luscious beaches.

It’s not bad per se, and yet it seems to reflect the very generational chasm it’s readily trying to comment on. George Hamilton utters the movie’s title and it’s all right there — utterly temporal and disposable in nature.

These moments and themes feel mostly empty and, again, while this might be precisely the point, it goes against our human desires. Either that or the movie is begging the audience to connect the dots. We want the critique wedded with entertainment. Because most of us are not trained to watch movies from a objective distance. Our mental wiring does not work like that especially when it comes to epics.

Jack is taken by a young starlet (Dalia Lavi) he meets by chance, thanks to her proximity to the troubled production. His and Veronica’s relationship becomes one of the focal points and one of the few deeply human connections in the picture.

Later, Jack’s bellicose benefactor, Maurice, falls ill. The added melodrama is to be expected along with raucous slap fights and the scramble to get the picture in under budget before the foreign backers try and pull out. The old has-been comes alive again — momentarily he has a purpose and companionship — until he’s besieged by new pressures.

Although it was purportedly edited down, it’s not too difficult to observe Minnelli doing his own version of Fellini’s earlier movie from 1960 with the dazed-out remnants of an orgy and a young Leslie Uggams singing her torch songs.

The apogee of the entire picture has to be Douglas and Charisse tearing through Rome in a mad fury. It’s the craziest, most chaotic car ride that can only be conceived in Hollywood; it’s so undisciplined and wrenched free of any of the constraints of realism. The back projections up to this point are totally expressionistic.

And as the car lurches and jerks around we realize we are seeing the film crossover: What we see behind the scenes and on the screen are one and the same, merely facades, and little more. It’s the kind of unbridled moment that could easily earn derisive laughter or genuine disbelief. There’s no way to eclipse the moment.

Instead, what follows is a cheery denouement out of a goofball comedy. Jack resolves to put his life back on track opting to leave behind his young leading man on the tarmac with a girl until they meet again. Hollywood, as is, was not totally dead — there was still some light in the tunnel — but if the box office receipts are any indication, tastes were changing.

3/5 Stars