The modern superhero genre as we know it began with Richard Donner’s Superman (1978) starring Christopher Reeve. Then, there were subsequent releases like Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) with Michael Keaton or even Wesley Snipes’s Blade (1998). Also, the first X-Men in 2000 has seen many subsequent additions throughout the 21st century.

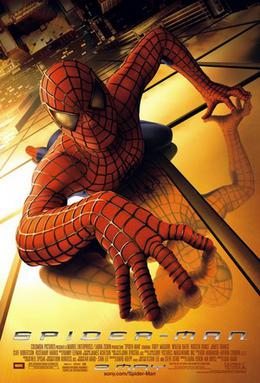

I’m no superhero cinema historian so there is plenty of room to quibble, but Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man feels like a portent of what was to come for a whole generation of superhero movies from Marvel and DC that have dominated the cineplexes since.

What I appreciate about the movie is how it’s not just a superhero movie, but a comic book movie. I mean this by how it conceives of itself. We have drama, but it’s not overly dark and oppressive; there’s room for humor and an acknowledgement that this is meant to be light and a genuine good time.

There’s an energy reminiscent of the teen movies of the 90s-2000s like Can’t Hardly Wait or She’s All That. Peter Parker’s in high school. He’s a bit of a dweeb with his nerd glasses and a nebbish persona, harboring a crush on Mary Jane Watson (red-headed Kirsten Dunst), the literal girl-next-door who doesn’t even know he exists.

Whatever people’s opinions of Tobey Maguire, I think all the ardent faithful hold him close to their hearts because of what he represents at the center of this film. He’s really the first Spider-Man in the modern era in a franchise that has now spawned so many progeny. And perhaps this is a gross generalization of the audience, but those who rally around him probably see Peter Parker as one of their own. They see themselves in him. Even if Tobey was a little old be playing a high schooler.

The movie willfully pulls out all these dorky bits of contrivance: Peter living next to MJ, though they’ve never seemed to talk before. Likewise, his best friend (a brooding James Franco) just happens to be the son of the man who effectively becomes Peter’s arch nemesis. But we forgive these things because aside from being bitten by a radioactive spider, Peter feels like a grounded human being in all other departments.

Willem Dafoe’s turn as The Green Goblin has a Gollumesque duality to it. It escapes me which film came first, but we see both his sympathetic father figure and the cunning conscience that comes alive in him as he hopes to make Oscorps into a success. He wants to prove all the corporate suits and military officials wrong. Even 20 years on, Dafoe’s always the kind of actor who gives the material its due and people admire and respect him for it. There’s no distinction between high and low art, whatever that even means.

Meanwhile, J.K. Simmons dives into the cartoonish nature of newspaperman J. Jonah Jameson without any hesitancy whatsoever. From his hair to his over-the-top demeanor and constant vilification of Spider-Man, he’s good for a few laughs.

But we want this broader larger-than-life quality because it fits with a world that in some ways mimics ours. Simultaneously, it’s meant to be fanciful and push us into a narrative of heightened imagination, romance, heroes, and villains.

What’s most refreshing about the film is how the drama has not yet been stricken with bathos — something that seems so en vogue now. It’s as if contemporary films need everyone to know they’re in on the joke and having a sardonic laugh at the expense of the stories and tropes themselves. We must undercut any genuine moment for fear of something being too soppy.

In Spider-Man the moments of sincerity are still there. The most evident are carried by Cliff Robertson, a revered stage actor and personality from the bygone era of Classic Hollywood. He utters the famed line “With great power comes great responsibility.” Sure we’ve heard these words so many times, they can feel like a cliché, but as he sits across from Tobey Maguire, the candor and simpatico between them is unmistakable.

I was also pleasantly surprised by the special effects of the film; they’re not always pristine and still they never pull us out of the movie completely. Raimi does a wonderful job giving us at least a few images to grab hold of. The most telling has to be the upside-down kiss between Spider-Man and MJ.

It’s the kind of visual iconography that by now feels emblematic of the film itself even as it gave a fresh face to movie romance. The key is how all involved do not scorn the moment; they still believe in the magic of the movies.

From the running time to the scope of the story, it feels almost quaint watching Spider-Man, and while there were no doubt sequels in the pipeline, it feels like it can function as a standalone movie. There’s not a lot of added dross either, but we still get a gripping story to take in and enjoy.

My final thought is only this. Principal photography for the film officially began in January 2001, and 9/11 not only changed New York’s skyline over the course of filming, it changed the film. But Spider-Man feels like one of those startling post-9/11 films.

We often think of stories where the material is inexplicably tied to those horrible events that stay with anyone who ever lived through them. However, I can’t help seeing movies like Spider-Man or even Elf, from the following year, in light of those events. Because their themes and heart unwittingly gave the audience laughter, thrills, and soaring spectacle in the face of terror.

These are not spoken sentiments, and yet they are baked into the very fabric of what these films are. They are wish-fulfillment and fantastical fairy tales in a world that often feels so harsh and foreboding. That’s why we still flock to stories like these even today. That’s part of why people still turn out to see Spider-Man. We like to look for the heroes.

4/5 Stars