People might come to Giant for James Dean. They might come seeking out the final film in George Stevens unofficial American Trilogy (including A Place in the Sun and Shane). Maybe it’s even the promise of a sprawling epic of monumental length and scope that turns out to be both a blessing and a curse by most accounts.

But this adaptation of Edna Ferber’s novel, despite all of this, is really a film about marriage and family in a world that’s constantly changing. Rock Hudson is a towering giant in his own right turning in a performance that works as quintessential Texan Jordan “Bic” Benedict. Elizabeth Taylor proves that far from a one-dimensional classical beauty, she has acting prowess as well delivering a spirited showing that gels with Hudson for the very fact that it often chafes against his characterization. Meaning they’re believable as husband and wife.

James Dean plays their marginalized ranch hand Jett Rink who is nevertheless treated well by Bic’s hardy sister Luz (Mercedes McCambridge) as well as Leslie while harboring a life long feud with Bic over the ensuing years.

Time turns this story into a battleground of two dueling giants. One a life long rancher of great stature. The other a modern figure blessed with a meteoric rise as an oil magnate. Their resentment carries through the generations as much as their differing fields reflect the sign of the times. The tectonics shift as the old guard of the Texas plains is replaced with a new breed of powerful men.

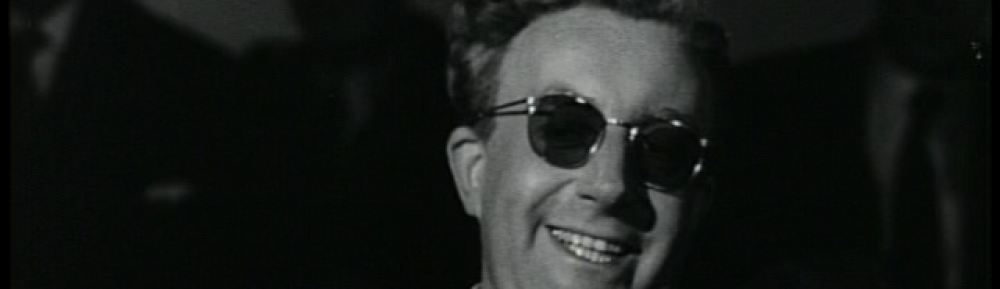

Of course, Dean’s performance is the stuff of legend and there’s an idiosyncratic, grumbling magnetism about it as only he could do. This isn’t Brando and it’s not even Monty Clift who previously played opposite Elizabeth Taylor in Stevens’ earlier picture. It’s James Dean showcasing his personal flare.

The final moments of his “Last Supper,” after his subsequent rise to glory, are devastatingly pathetic. The mighty oil tycoon of Jetexas falls into utter disgrace crashing to the floor of the empty banquet hall with a clatter. Rolling around in a drunken stupor, making a shambles of his grand exhibition of wealth, and simultaneously concluding Dean’s last scene in front of an audience.

His life would be taken even before Giant finished filming, some of his last scenes of dialogue being reread by close friend Nick Adams, his temperamental nature and habit of mumbling lines impacting the production even after his passing. Still, George Stevens himself, despite the insurmountable hell he was put through, and the hits his shooting schedule took, even admitted that Dean was something special.

You might not like him but all of us seem to gravitate to him for some inexplicable reason. He carries our gaze with his ticks and his delivery. It’s as if he forces us to take heed even out of a necessity to understand him, his head downcast, his hands fidgeting and such, all a ploy to carry our attention. It generally works.

Yes, we lost him so young but the beauty of Giant’s epic stature is that in cinematic terms Dean was blessed with a full life. We saw him as a fiery youth in East of Eden (1954) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and in Giant he evolved into an equally tortured man who grew old before our eyes. That’s the magic of the movies. But sometimes it’s so easy to have his legend overshadow all others.

The latter half of the film is really about the Benedict family evolving with the maturation of their children. Dean is worth a closer look certainly, but I’m inclined to enjoy the performances of Carroll Baker and Dennis Hopper nearly as much if only for the simple fact that they’re less heralded.

Baker is the daughter caught in the throes of romance and decadence who finds Jett Rink more fun partly for the very fact that her stuffy parents abhor what he has become. Meanwhile, Hopper brings a surprisingly earnest candor as the Benedict’s eldest son with aspirations to be a doctor instead of a rancher, pushing against family tradition, subsequently marrying a Mexican-American bride, and facing the unfortunate ostracization that comes with such a life.

Some of the most evocative scenes are actually held between Hudson and Taylor. To most, their careers were known for personal lives exploited by tabloids. They don’t get the same adulation as Dean as actors. Still, in this film, they do something quite spectacular in a more unassuming way. They quite authentically reflect the life of a married couple as their romance and life together waxes and wanes over the years. That includes Jett Rink’s onslaught and the trials with kids but, at the core it’s just the two of them, grappling with it together.

Because this is a film that unfolds over decades we come to appreciate the changes that come over the characters and not so much the makeup or touches of gray. More important are the strides they make in their lives or even how they remain the same.

They model what it is to be young and in love, to quarrel and bicker and to make up and to be diplomatic and to have dreams and aspirations and to want the best for your children and at the same time hold grudges and feel like the ones you love are purposely trying to undermine you.

To begin with, this is a fairy tale romance of opposites. Hudson is the formidable Texan bred as a rancher and he comes to the upper echelons of eastern society looking for a stallion and he comes back with a bride instead.

She comes to his country initially welcomed and then feeling like an outsider in a land that is so set in its ways. Men and woman are expected to exist in certain spheres. White folks don’t fraternize with Mexicans. And cattle barons tame their land and breed their stock like their fathers before them. It’s tradition and they stick to it. Bic Benedict is raised in that Texas tradition dating all the way back to the Alamo, his stock proud, fiery, and tough.

Still, his wife Leslie is just as audacious but in different ways, testing his sensibilities and testing the matrimonial bonds of their marriage. She rather comically proposes her own marriage, looks to break up the boy’s club mentality that dictates the culture, and tramples over the de facto laws of the land in favor of goodwill to all. That means if a baby is sick, she fetches a doctor. The color of its skin makes no difference. In that atmosphere, it’s radical that she extends kindness to everyone, not simply her own “kind” as it were, whether divided by class or racial barriers. Ultimately, it’s a testament to the sorry state of affairs but also of her personal convictions and they bleed into the rest of her family.

The final showcase comes not in his front and center bout with Jett Rink because although we’ve been expecting it for decades, as such it never comes. Jett’s not worth it anymore. Instead, Bic’s shining moment comes in, of all places, a roadside diner. He’s not as strapping as he used to be and he gets wailed on something awful. But in this moment as he’s duking it out with a local bigot, the platform that he stands on is not simply about his family name or his own personal honor as a Benedict but along the planes of what is morally right and wrong.

Rejecting service to people based on the color of their skin is inherently wrong. Disrespecting people of other races can and never should be accepted. Years before he would have never taken a stand on such touchy issues but he’s matured in that regard and his wife falls in love with him all over again. She sees first hand why she grew to love this man.

He lies there on the floor heaving and bloodied with food flung all around him the oddly upbeat throngs of “Yellow Rose of Texas” still whirring on the jukebox but ironically Leslie has never been more proud of her man. It’s that paradoxical maxim written about many times. Blessed are those who are persecuted for doing good.

Most modern viewers will honestly thank their lucky stars that they don’t make epics like this. But there’s something fleetingly enchanting about these old-time vehicles that managed to encompass so much space with grandiose ambitions and awesome imagery full of million dollar skies and fluffy clouds as far as the eye can see.

The West is dead as is the American genre. The stars as we knew them are no more. We are still a nation struggling with issues of race and class. Love and marriage. That mixture of nostalgia and timelessness still makes Giant a draw. George Stevens is one of The Great American Directors and though Shane (1953) will remain his unassuming masterpiece, Giant deserves at the very least a modicum amount of respect as a dying breed of American epic.

4.5/5 Stars

Note: Entry in The Elizabeth Taylor Blogathon!

Initially, I Remember Mama comes off underwhelmingly. It’s overlong, there’s little conflict, and some of the things the story spends time teasing out seem odd and inconsequential at best. Still, within that framework is a narrative that manages to be rewarding for its utter sincerity in depicting the life of one family–a family that feels foreign in some ways and oh so relatable in many others.

Initially, I Remember Mama comes off underwhelmingly. It’s overlong, there’s little conflict, and some of the things the story spends time teasing out seem odd and inconsequential at best. Still, within that framework is a narrative that manages to be rewarding for its utter sincerity in depicting the life of one family–a family that feels foreign in some ways and oh so relatable in many others.