The L.A. Times headline in 1951 read: “Peggy Dow Sketches Future as She Quits Hollywood to Wed”

Many people recall how Grace Kelly famously married Prince Rainier of Monaco and from thenceforward left her stirling Hollywood career behind out of a sense of love and duty. That’s how the narrative was written anyway.

At least in the case of Peggy Dow Helmerich, it was never about sacrificing her career for the sake of her family. She wouldn’t have had it any other way, going on to raise 5 sons with her lifelong husband, Walt Helmerich, in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

What makes it such a lovely story is how she left behind the “Hollywood Dream” and lived a lovely life of contentment outside of the West coast rat race. Far from being a wasted talent that could have been, she simply reallocated her talents becoming synonymous with the arts in Oklahoma. And there’s nothing more admirable than raising a family.

In recent days, I got interested in Helmerich’s career. She is still with us today and before COVID days, she still made a decent amount of public appearances in her hometown as well as graciously agreeing to be interviewed by the Jimmy Stewart Museum, among others. It’s been a cache of wonderful information about old Hollywood and her part in it, but it’s also given me a greater estimation for the woman herself.

I felt compelled to acknowledge her, not only as a bright Hollywood talent with some enjoyable films to her name (including Harvey), but also as a lovely human being. I’m not sure if Mrs. Helmerich will ever see this, but hopefully, it can act as an introduction to those who aren’t as familiar with her.

Although she was only in Hollywood for several years, coming off university at Northwestern, she was touted at Universal-International as a rising starlet and her contemporary portfolio suggested as much.

In 1950, she was not only featured prominently on the cover of Life Magazine, but she also presented Edith Head her first Oscar at the Academy Awards for costume design. Famed gossip columnist Hedda Hopper rated Dow highly, writing that she “Endowed Roles With Zest and Impact.” In 1951 she even accepted an award from Harry S. Truman in laud of Bright Victory, and its portrayal of servicemen.

If there was a beauty to actors being salaried to specific studios, it meant they had the opportunity to be in a slew of movies and therefore take on many different roles in an extremely short span of time. Peggy Dow only worked for a couple years at Universal-International and still found herself in 9 movies. Here are some of them.

Undertow

It’s not a pretty picture, but in an era saturated with noir, Undertow does give a fairly prominent role for Dow as an intrepid schoolteacher who meets a reformed criminal (Scott Brady) in Reno and shares a flight with him, only to later provide him asylum from the Chicago mob. Against the run-of-the-mill plot of a wanted man exonerating himself, Dow ably showcases her charms with warmth and a touch of class. The only question remains how will Brady end up with her since he already has a bride-to-be already waiting in the wings? It all works out in the end and boy gets girl.

Woman in Hiding

It’s a superior picture starring Ida Lupino in trouble, Stephan McNally as her treacherous southern boy of a husband, and Howard Duff plays the genial foil, providing support in her time of need. The title is straightforward enough and Dow’s part is pretty small, but it’s a juicy bit. She plays a scorned southern belle who gets slapped around during a cabin rendezvous and still manages a conspiratorial tone later on. Although it wouldn’t become the norm, it certainly would have aided in not totally typecasting her if she had wanted to stay in Hollywood.

The Sleeping City

It’s a mostly forgotten noir set in a hospital with Richard Conte as an uncover agent investigating a mysterious murder. With the sweet and diffident Colleen Gray as a nurse, it’s a bit difficult to know where Dow will fit into the picture. Sure enough, she shows up at the tail end as the heartbroken wife of a dead man brought in for questioning. All it amounts to is sharing a walk and talk with Richard Conte. That’s about the extent of it. Thankfully, the best was yet to come!

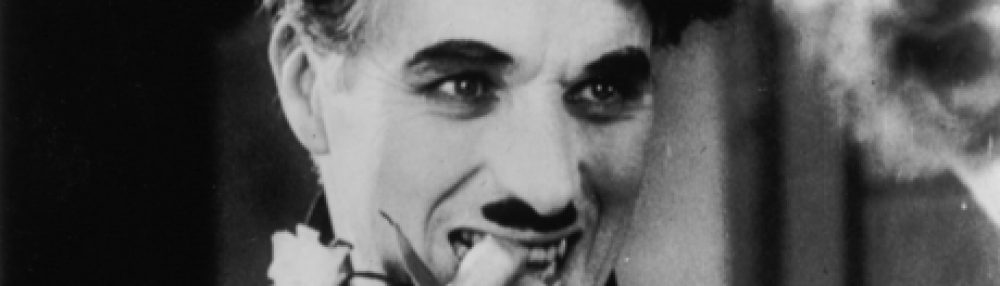

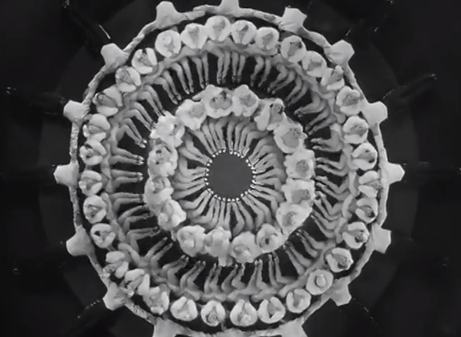

Harvey

Dow stated in interviews she actually didn’t want to feature in Harvey as a nurse because she was earmarked to play an Indian princess in some western opposite Van Heflin. It was her agent as well as her beau at the time, Walt Helmerich, who both encouraged her to take the part from the hit play now starring James Stewart. Time certainly has looked kindly upon that decision.

Now 70 years on and Harvey is still a beloved classic about a whimsical man who converses with an invisible rabbit and sprinkles a bit more pleasantness into the world. It would not be a stretch to say I would have never known Peggy Dow without Harvey. It’s not a flashy part, but what comes through is her beauty and natural courtesy gelling so nicely with Stewart’s characterization as Elwood P. Dowd. It just makes me smile, and she does too. It still holds up for me.

Bright Victory

It comes in the fine tradition of many of the war rehabilitation movies, in this case, following a soldier returning from WWII without his eyesight. He struggles to put his life back together with the help of his doctors and the tough love of his buddies. Dow got her biggest chance this time opposite Oscar-nominated everyman Arthur Kennedy.

She plays a warm and virtuous woman who sees through a vet’s gruffness, treating him decently because she sees all he’s had to overcome. After getting off on the wrong foot, they build a comfortable rapport. The only problem is that he already has a beautiful fiancee (Julie Adams) waiting for him. Thankfully, she’s hardly a terror, but the way the cards fall, Kennedy still ends up with the girl who has waited faithfully for him. It’s a joyous crescendo in a movie that certainly has admirable intentions promoting empathy and racial tolerance. Dow shares some tearful moments opposite Kennedy that are absolutely heart-rendering.

You Can Never Tell

At its heart, it’s a goofy fantastical comedy that has a bit of the DNA of the Shaggy Dog or Angels in the Outfield. A dog is bequeathed a giant fortune, quite peculiar, only to kick the bucket, quite suspicious. He’s reincarnated as a Dick Powell private eye prepared to get to the bottom of his own murder. Far from a villainess, Peggy Dow is his faithful caretaker who is next in line to the fortune. However, in all her good-nature, she doesn’t know someone has their designs on her (and the money). It’s ludicrous and fluffy if altogether harmless entertainment, enjoyable for what it is.

I Want You

This movie shares some similarity to Bright Victory in that it evokes an earlier classic in The Best Years of Our Lives. In fact, Samuel Goldwyn was trying to match his earlier success bringing back Dana Andrews in a story examining the effects of war on three generations of a family in Middle America. Robert Keith is the father and WWI vet whose eldest son (Andrews) went off to WWII, leaving behind his wife (Dorothy McGuire). Now, with the current conflict in Korea, the next in line (Farley Granger) is to be sent off.

He’s a brash young man involved with his car and girls. His best girl happens to be Peggy Dow. She’s been off to college, gained education, experience, and breeding. Her father is not too keen about her hometown beau, and so he has an uphill climb to woo her back. There are several facets to the movie, and if it was allotted more time to tease out its themes with greater nuance, it might be more well-remembered today. The meaning certainly is there if it’s not executed to a tee. Regardless, the performances carry a genuine warmth, and it’s a delight to watch the young love of Granger and Dow breeding between them. What a shame this would be Dow’s final time in the Hollywood spotlight!

Beyond Hollywood

We will never know what Marnie would have looked like if Princess Grace had come out of retirement to work once more with Alfred Hitchcock. And the same might be said of Peggy Helmerich. She was married and already a mother of her first when Hollywood tried to coax her back one last time in 1956.

It wasn’t just anyone either; it was one of the industry heavyweights in William Holden. He was set to play a pilot. No, this wasn’t another Bridges of Toko-Ri, but a picture called Toward the Unknown. Ultimately, the former actress passed on the opportunity and never looked back!

“Why would you want to stay in this business?’ I thought he was crazy, and I told him, the same reason as you: I’m an actor. But it turned out that he was fascinated with Walt because Dick was fascinated with business. He told me: You get married to Walt, and you come back to Hollywood, and this is what’s going to happen: It won’t work out. He asked me to come up with five happy married couples in Hollywood that we knew, and we had a hard time doing it.”

So in the end, a truncated Hollywood career seemed like a small price to pay for lifelong happiness. As alluded to already, Dow gladly turned her faculties towards raising a family with her husband of over 50 years Walt Helmerich as well as investing in her community. It’s no coincidence that the University of Oklahoma school of drama is named after her as well as a prestigious Distinguished Author Award.

However, more then any of this, whether it’s through her screen roles or the interviews that she gave, it’s obvious that Peggy Dow Helmerich is a classy, warm-hearted individual. When asked what she wanted to hear from God when she arrives at Heaven’s gate, she responded, “Come in.”

I’m not sure if I will get the pleasure of making your acquaintance in this lifetime Mrs. Helmerich, but I certainly hope I might get the privilege of seeing you in the next. I will tell you how much Harvey impacted me and how pleasantness really can go a long way in this world of ours. I think you exemplified that as well as anyone else. I wish you all the best.