The opening title card sets the stage in strife-torn Dublin in 1922 with a reference to Judas, the man who betrayed Jesus Christ to be killed. The allusive nature of the story becomes apparent only with time, connecting with John Ford’s own deeply religious inclinations as an Irish Catholic.

The opening title card sets the stage in strife-torn Dublin in 1922 with a reference to Judas, the man who betrayed Jesus Christ to be killed. The allusive nature of the story becomes apparent only with time, connecting with John Ford’s own deeply religious inclinations as an Irish Catholic.

I won’t say Ford’s able to make a soundstage more atmospheric than the real place because reality would provide a grittier, more authentic ambiance, but here we have the mist, large vacant sets, and crumpled up newspapers that flutter around like tumbleweeds. It’s Dublin as can only be conceived in the dream factories of the studio system.

Some might forget before John Wayne was one of his primary avatars, Victor McLaglen came to represent Ford’s version of hardy masculinity even earlier, and it’s no different here. Even when he was displaced in later years, he still found time to turn up in the director’s pictures, most notably in The Quiet Man and his cavalry trilogy. Ford never seemed to forget actors who had put in their service with him.

As The Informer set down its roots, it feels a bit like watching Hitchcock’s England pictures from the ’30s. You can see the early brushstrokes of the master, but it’s almost as if the technology hasn’t quite caught up with their ambitions and the capabilities of what they’re yearning to do. Sound, color, lighting, and the like would improve in the ’50s and ’60s as would both men’s budgets leading to some of their finest achievements and a plethora of the most lauded pictures Hollywood has ever known.

For now, they work with what they have and manage to spin a decent cinematic yarn all the same. Because necessity is the mother of invention; still, it’s also about how you utilize the time and resources on hand to make something as substantive as possible.

The Informer was made for RKO probably due to the fact no one else was willing to take a chance on it. It’s a meager picture in many regards, and this is easy to forget since it was a stunning success during that year’s award season. But it was a film made for a relative pittance over the course of a couple of weeks plus change.

While one would probably never call it Ford’s most profound achievement, you can tell he’s put his blood into it — his history as a proud Irish-American — and its core dilemma is a powerful bulwark to build a film around and an acting performance.

Gypo Nolan (McLaglen) is a man caught in the middle of civil unrest plaguing the lands since their inception. The British think he’s with the Irish and the Irish think he’s with The British. Mostly he’s out for himself just trying to subsist and earn himself a bit of merriment. Still, he can’t scrounge up a job from either side. It’s far from a desirable place to be.

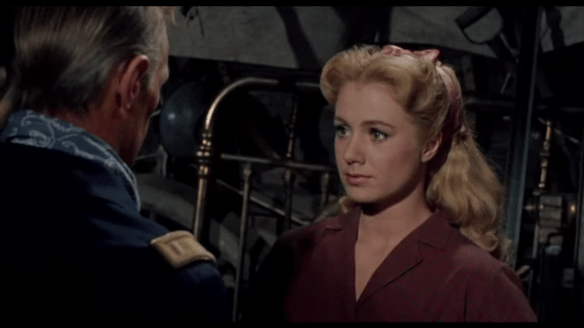

He does have a few friends: Katie (Margot Grahame) is his lady although because he’s not good for much money, she works as a streetwalker to scrape out a living. Still, she’s devoted to the big lovable oaf. Another is Frankie McPhillips (Wallace Ford), a wanted hoodlum for the IRA resistance and a brother in arms for Gypo. They’ve grown up together and as is the prerequisite for a community like this, their friendship is forged in a life lived in proximity. Gypo loves the man, but he’s also penniless with no prospects.

It’s not exactly 30 pieces of silver, but Gypo makes a rash decision to sell out his friend — this isn’t so much of a spoiler — because this becomes the context for the rest of the movie. He’s tortured by his conscience even as no one suspects him in the wake of the tragedy he instigated against his friend and the man’s grieving family.

His only defense is to swim in self-absorbed debauchery. It gets him out of the moment providing a brief escape from his guilt. He belts a policeman and another lad on a street corner before wrangling fish and chips for a whole host of onlookers in a show of drunken generosity thanks to his newfound wealth.

In another scene, he stumbles in on a hotsy-totsy establishment run by a local matron where all the men and women wear top hats over drinks, conversation, and other things. He bowls them over with his rowdy entrance pushing down pipsqueak and gathering pretty girls up around him. These all feel like a part of his mental smokescreen.

Behind the scenes it’s a much grimmer scenario as the pragmatic Dan Gallager (Preston Foster) sends his cronies out into the streets to track down Frankie’s betrayer. This isn’t a mission of mercy. They live in a kill or be killed economy, and they’re prepared to take the necessary actions to preserve their cause against traitors, even those with deep roots in the community.

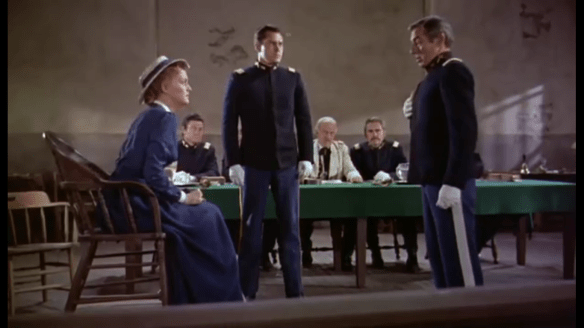

The drunken Gypo is pulled into a meeting with another suspect (Donald Meek) as the truth is slowly sussed out. The tribunal standing by has echoes of M, though it’s now been superimposed by this sense of Catholic guilt and justice.

McLaglen makes his way through the entire movie boisterous, gruff, and drunk like any good McLaglen performance except this easily must be the bar by which to judge all others. It’s either a really good job of acting or Ford helped him get into the part with a little trickery and added encouragement from the spirits. At least that’s how the story goes. Either way, it works with the actor dispensing this trail of blustering, sniveling, disoriented guilt, and gravitas making the picture go.

Dudley Nichol’s script doesn’t necessarily employ great prose — it’s not a thing of beauty — but Ford is able to utilize its framework to tell a worthy story. The final images culminate in the ultimate biblical picture.

Gypo stumbles into a church with one final chance to pay recompense for his sins. He gains absolution from the Mother (Una O’Connor), standing before the Crucifix, arms outstretched (May God Have Mercy on His Soul). The sentimentality doesn’t feel like typical Ford — though he could certainly be deceptive about it — and this form of religious iconography is something relatively apparent even in his final picture Six Women.

The Informer’s unparalleled success paved the road for him ahead with many great entries to come. Ford certainly was a master in blending classical storytelling with his personal vision. It shows how personal filmmaking can break through the barriers and resonate with audiences on an impactful level.

4/5 Stars

Recently,

Recently,