It occurs to me, like with Jean-Pierre Melville (and so many others), that the landscape and context of the war years left such a lasting impact on Robert Rossellini, and they are made manifest in his films. Although it’s shot over a decade later, there’s still a lived-in quality, committed to a kind of authenticity.

Whereas others, namely Americans, experienced the war and then returned home (albeit with PTSD), for these men war was a stipulation of everyday life. It was the water they drank and the bread they ate, suffusing into all aspects of society.

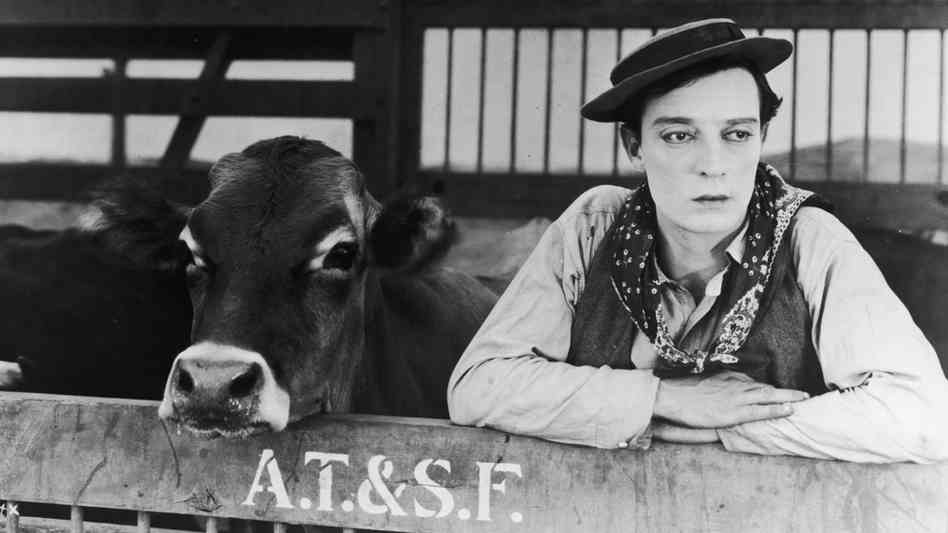

Vittorio De Sica is called upon to play a far different kind of gambler than he was in The Gold of Naples. His blustering lunatic is displaced by a miserable loser stumbling and bumbling his way through a mediocre existence.

Emmanuele Bardone, like everyone else, is getting trampled on by this war, just trying to survive. His debts pile up, no thanks to his rampant gambling habits. He pleads with his girlfriend, a fair-weather beauty (Sandra Milo), who has had just about enough of the meager life he can offer her on his half-baked promises. It’s to no avail. She’s not intent on bailing him out again.

Thus, he must find other means to scrounge up the funds to pay off a German Sergeant Major. They’re buddy-buddy — gambling acquaintances — but it doesn’t keep them from attempting to stab each other in the back. It’s one of those uneasy partnerships engendered by the war. Because Bardone is such a man: feckless, unctuous, self-serving. He’s always looking to get ahead, whether by courting Nazis or fellow Italians frantic to track down missing relatives at any cost…specifically well-off Italians.

Physically, Vittorio De Sica strikes me as a man whose stature and features are impressive, quite effortlessly handsome. Yet, he’s capable of bringing something out of them, wringing the comedy and the tragedy with the body God has given him.

I don’t know why exactly, but I want to compare him to Cary Grant — a man who doesn’t take himself too seriously — so whether debonair or a bit of a cad, we still find it within our hearts to root for him.

He vows to help a rich widow and her daughter-in-law in what feels like just another confidence game preying on their desperation. His gambling gets interrupted by air raids, and he crawls back into the life of one of his other girlfriends (Giovanna Ralli).

Something else happens that he knows absolutely nothing about, but it changes the course of the entire picture. A famed dissident is accidentally shot dead at a roadblock, but a cover-up ensues. The capture of Generale Della Rovere is spread around town despite a botched assignment within the Nazi ranks. Now they must find a man to fill his place: Bardone is fingered for it, and he has no bargaining power in this economy.

We’re privy to the Nazi’s intricate filing systems and notecard records helping to mechanize their ruthless war machine, but they’re also more than prepared to play spy and counterspy with a sorry drifter’s carcass.

Narrative-wise it feels like the story can easily be split into two distinct segments. Because it takes a good hour before De Sica is actually cast as the Generale and suddenly the stakes of his new life are raised.

This film was one of Rossellini’s more profitable efforts and with it came an actual high-concept idea. But this never feels like what the director is truly interested in. He skirts around the “plot” as much as possible to make this story about a character and a world.

When he is finally in prison, all the rebels and convicted patriots pledge their services through cell windows and the surrounding walls. They believe him to be who he says he is…meanwhile, Bardone maintains his pact with Colonel Muller to coax out the Generale’s contact on the inside. He’s met with a crisis calling for some self-examination.

Aside from De Sica, Hannes Messemer has to be the other obvious standout as the German SS man. He’s hard and difficult to like, especially when wearing a Nazi uniform in wartime. However, he’s not a cartoon and even momentarily there are these ever so faint flashes of nobility. He cannot be pinned down; his duty as a military officer trumps everything, and yet the contours of his person make us grapple with more than we are used to in a Nazi.

Because as much as we don’t want to admit it, every Nazi was a human being. He is another soldier, driven by duty, perhaps an ideology, and yet still complicit in these grievous sins against humanity.

There’s also what feels like a level of moralizing to the picture. Because we have this space created. It is now the 1950s. Suddenly Rossellini is out from under the complete specter of the war, and he’s able to make his hapless vagabond into an unsolicited hero. A cynic could brand it as little better than a post-war potboiler.

And yet as he tramps out into the snowy prison yard, there’s a steely conviction about him for the first time in the movie. It takes the obvious arc of this character and imbues it with something fleetingly profound. Surely this is the sensibility of Rossellini.

I recall Lino Ventura in Army of Shadows, Marlene Dietrich in Dishonored, and now Vittorio De Sica. They all share something in common. They were valiant heroes to the end and sometimes their heroism is unwonted. It doesn’t matter so much the road you’ve taken as long as you make it there in the end. There was never any doubt.

4/5 Stars

Hirokazu Kore-eda has quickly become one of my favorite Japanese directors, and I consider it fortuitous that this affinity has cropped up in such a fertile period. Shoplifters is a high watermark in his already illustrious career.

Hirokazu Kore-eda has quickly become one of my favorite Japanese directors, and I consider it fortuitous that this affinity has cropped up in such a fertile period. Shoplifters is a high watermark in his already illustrious career.