Woman in Hiding doesn’t waste any time. A car races down a twisting highway only to go careening through the side rails into the drink. The car and its occupant look to be obliterated. Yet we have the dead talking, Ida Lupino whispering to us from the grave. Could this be a situation akin to Joe Gillis in Sunset Blvd (1950)? We’re forced to wait before making any prognostication.

The story is set in North Carolina and as such, you have this lingering undercurrent of southern glory and heritage wrapped up in the wounds of secession and racial prejudice. There’s even reference made to the deep lurking traditions of the South with its pitchforks and rocks, of people who wouldn’t give up and wouldn’t allow their way of life to die. It’s actually rather unnerving rarely seeing an African-American character in this Hollywood tableau almost as if they’ve been erased.

Still, the locals go about their business dredging the local waters for the automobile and the missing Mrs. Deborah Clark (Lupino), even calling on the assistance of an old cannon, yet another relic from the aforementioned lineage. This is the backdrop against which Woman in Hiding plays out.

Because Seldon Clark IV (Stephen McNally) came out of this pedigree — tall and handsome, but proud and driven with maintaining the family standing, even to the point of delusion. He’s worked in the mill of a Mr. Chandler making many unwanted passes at his daughter Deborah.

For the time being, nothing comes of it because her father gives the boy a stern talking to, seeing right through the arrogant creep and the rest of the buffoons who beget him. In fact, it is at this point Lupino feels sorry for him — trying to defend him.

The story takes its most drastically abrupt turn on a single cut, when, in a matter of seconds, it comes out the forthright and perceptive old man died in a freak accident. Who was by his side unable to help him? Seldon Clark of course. It’s an obvious equation of two plus two, but, again we must wait until everything unfolds.

Marriage is proposed the day of the funeral, thus tying the knot (and the mill) between Deborah and Seldon. Their subsequent honeymoon at a cabin getaway is rudely disrupted by a former girlfriend. Peggy Dow debuts as a conniving southern belle on equal footing with her darkly vindictive suitor. It instantly rips away any pretenses we might have from her more widely remembered turn in Harvey (1950) as she gets backhanded for her many scandalous insinuations.

Could she, in fact, be the victim of the scenario? Doubts creep in? The first of many as Seldon’s colors become more and more obvious even to his wife. One of the most generous compliments that can be offered to Woman in Hiding is how it wears its melodrama brazenly on its sleeves.

It evokes a helpless world akin to Road House (1948) where nature is a trap — a place in which to be hunted like an animal, in this case, confined to a nightmarish marriage. The narrative does fold over itself and we realize where we find Deborah.

She is a woman caught in a state of matrimonial helplessness, in a society where she has little agency to do or say anything to free herself. It’s the same anxiety film noir of the post-war era gorged itself on, for both men and women. Because it becomes apparent the dividing line between victim and femme fatale is razor-thin. Really all that matters is the point of view provided.

From Deborah’s flustered perspective, there is a vague sense of searching out Patricia Monahan (Dow) because maybe together their corroboration might be able to put Seldon away. Just maybe someone might listen to the truth then.

For the time being, staying dead is the most auspicious decision. Deborah takes to the road to disappear for a while and make some money on the side waitressing. But there must always be a foil and in this case, it’s a man named Keith Ramsay (Howard Duff).

He’s the genial man behind a newspaper stand striking up a conversation with a woman on the run. He seems like just the type of character who might provide a shoulder to lean on, whether solicited or not. In a world where everyone’s overstimulated with get-rich-quick schemes and radio giveaways, he seems decidedly unconcerned with the rat race as he works at his pop’s shop.

However, he does become a shoulder to lean on — offering comfort — but he’s also a part of the problem. Because this tale gets its punch from a woman being hunted, when she should, in fact, be a victim. In this regard, it’s a precursor to the same problem at the core of Blue Gardenia (1953) as the newspapers start treating her as a fugitive.

Because even as the local hotel is overrun by a traveling convention of drunken out-of-towners and conga lines, darkness can still find its way back in down the stairwells. The most excruciating development comes with the connection between our favorite fellow and the dastardly husband. He has no idea what’s he’s doing when he makes the identification.

Even as Deborah is taken back by her husband and Monahan turns up again only to be stepped on, the story must culminate where it began. In the same small town, at the dead of night, inside the mill. There’s something to knowing what’s going to happen and still having a potboiler raise the pulse. It comes down to the old adage, it’s not the destination but the road taken.

It also comes from actually genuinely caring for a character and as one of the best — some might even say an underrated actress — Ida Lupino plays the victim with an inbred resiliency, making the audience strive for her safety even as we sit powerlessly in the theater seats. It’s not some monumental derivation of the tried and true formulas, but audience identification goes a long way.

3.5/5 Stars

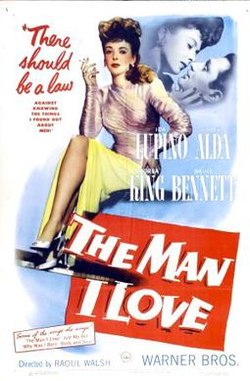

It feels like we might have the courtesy of a bit of Gershwin masquerading under the cloak of noir. We find ourselves at a hole-in-the-wall jazz joint after hours. Club 39 feels free and easy with an intimate jam sesh. Petey Brown (Ida Lupino) is having fun with a rendition of “The Man I Love.”

It feels like we might have the courtesy of a bit of Gershwin masquerading under the cloak of noir. We find ourselves at a hole-in-the-wall jazz joint after hours. Club 39 feels free and easy with an intimate jam sesh. Petey Brown (Ida Lupino) is having fun with a rendition of “The Man I Love.”

“Doesn’t it ever enter a man’s head that a woman can do without him?” ~ Ida Lupino as Lily Stevens

“Doesn’t it ever enter a man’s head that a woman can do without him?” ~ Ida Lupino as Lily Stevens Father hear my prayer. Forgive him as you have forgiven all your children who have sinned. Don’t turn your face from him. Bring him, at last, to rest in your peace which he could never have found here. ~ Ida Lupino as Mary Malden

Father hear my prayer. Forgive him as you have forgiven all your children who have sinned. Don’t turn your face from him. Bring him, at last, to rest in your peace which he could never have found here. ~ Ida Lupino as Mary Malden They Drive by Night is a surprisingly engrossing picture and I only mention it for its obvious relation to High Sierra. It came out a year earlier, helmed by Raoul Walsh starring George Raft, Ann Sheridan, Ida Lupino and, of course, Humphrey Bogart. The important fact is that if Walsh had gotten his way, he would have cast Raft again as Hollywood’s perennial tough-guy leading man.

They Drive by Night is a surprisingly engrossing picture and I only mention it for its obvious relation to High Sierra. It came out a year earlier, helmed by Raoul Walsh starring George Raft, Ann Sheridan, Ida Lupino and, of course, Humphrey Bogart. The important fact is that if Walsh had gotten his way, he would have cast Raft again as Hollywood’s perennial tough-guy leading man. He’s not about to lose his nerves or take his eyes off the objective but the two young bucks he’s thrown in with (Alan Curtis and Arthur Kennedy) carry the tough guy bravado well but there hardly as experienced as him. He’s not too happy about the girl (Ida Lupino) they have hanging around either because she’s an obvious liability. In his experience, women squawk too much. The man on the inside (Cornel Wilde) is even worse, a spineless hotel clerk with even less nerve.

He’s not about to lose his nerves or take his eyes off the objective but the two young bucks he’s thrown in with (Alan Curtis and Arthur Kennedy) carry the tough guy bravado well but there hardly as experienced as him. He’s not too happy about the girl (Ida Lupino) they have hanging around either because she’s an obvious liability. In his experience, women squawk too much. The man on the inside (Cornel Wilde) is even worse, a spineless hotel clerk with even less nerve. In an unassuming act of charity, Roy has a doctor friend take a look at Velma and ultimately pays for the surgery that heals her ailment completely. Still, if the story ended there it would be a happy ending but with the heist in the works, Roy is not so lucky. He pulls off the job and makes his getaway but with most any cinematic criminal activity in Hollywood’s Golden Age there must be repercussions. After all, that’s what keeps things interesting and it’s true that Roy and Marie are able to lay low for a time but soon the word is out and the gangster is a wanted man.

In an unassuming act of charity, Roy has a doctor friend take a look at Velma and ultimately pays for the surgery that heals her ailment completely. Still, if the story ended there it would be a happy ending but with the heist in the works, Roy is not so lucky. He pulls off the job and makes his getaway but with most any cinematic criminal activity in Hollywood’s Golden Age there must be repercussions. After all, that’s what keeps things interesting and it’s true that Roy and Marie are able to lay low for a time but soon the word is out and the gangster is a wanted man.