I recall my dad sharing a recollection about On The Beach. Back when it came out he went to the drive-in with his family, and they took in the movie. He fell asleep part of the way through only to wake up and the movie was still going. While not necessarily a profound observation, the film is unequivocally long. For some, it will verge on the doldrums, especially for a story about the end of the world.

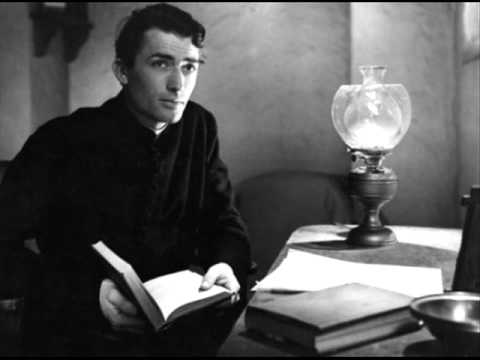

However, I am tempted to like it for some of the creative decisions it chooses (and in my father’s defense, he never said he outright disliked the movie). It acts as one of the first prominent films detailing the aftermath of a nuclear war. Also, unlike many of its contemporaries, it leads with a cold open closeup on Gregory Peck’s face as he commands a submarine. The camera is quick to maneuver through the space showing us all the levers and nobs with shipmen scurrying around carrying out their various duties.

It’s already a different feel than something like Run Silent, Run Deep (1958). We can actually breathe because there is no suffocating atmosphere to speak of. That’s what makes the emptiness of the space on the outside so startling. It’s almost too open; it’s all but void of meaningful life except for small envoys existing far enough away from the disaster zones.

Conceptually, the apocalyptic near-future is an intriguing world to come to terms with, just as it is frightening. Because it’s a hybrid society still existing in the world and only time will tell if it can subsist.

We familiarize ourselves with a segment of humanity now living in Australia, and America seems to be decimated. Everyone refers continually to “These Days” — it implies the allowances made in such extreme circumstances. People cannot go on living the way they always did, and things formerly unheard can happen without so much as a bat of an eye.

Shortage leads to a random assemblage of old and new technology to get by. For transportation, electric trains and horse-drawn carriages have a function. And yet for amusement, folks still have beach days soaking in the sun as if nothing is awry. It seems like small consolation for the 5-month expiration date being put on the world.

At first glance, On The Beach doesn’t seem to be about much. It’s really about one major event scattered with the residuals of human relationships. One of our main players is Commander Dwight Towers (Gregory Peck), a widower who lost his family to the catastrophe while he was on duty. Currently, he has come to Melbourne to receive a briefing from Admiral Bridie (John Tate) on what they might possibly do next.

Struggling with survivor’s guilt, Towers strikes up an intimate relationship with one Moira Davidson (Ava Gardner). A radio signal originating in San Diego calls him back to the sea, and he heads out, unsure if he will ever see her again — yet another person he must reluctantly say au revoir to.

Anthony Perkins fits into the story as a younger version of Towers, Lieutenant Peter Holmes. He still clings onto his young family while worrying about what might happen to their slice of marital bliss. Because she is less-remembered, I am apt to especially be interested in Donna Anderson who gives a sincere performance as his wife (though it starts to unravel as the clock ticks). Mary cannot bear the implications of their society, as they have a newborn and with her husband away, there will be no telling what will happen to them. It unhinges her.

The most ominous shot during the voyage is an eerily empty Golden Gate Bridge, indicative of the entire West Coast. It’s literally dead. When they finally arrive in San Diego, it proves to be a near ludicrous dead-end involving a window shade and a coke bottle. Even Yankee know-how wasn’t able to avoid utter destruction.

It occurs to me On The Beach is not trying to exploit the situation, but it is using the backdrop to say something as Stanley Kramer always tried to do with his pictures. While he’s not the most virtuoso of filmmakers, his intentions are always upfront, which is admirable.

The director always aligned himself with fine acting talent even affording a trio of former musical stars shots at dramatic parts to reshape their prospective images. That in itself takes unwavering vision. In this one, Fred Astaire gets his chance as the hard-drinking, chain-smoking, acerbic scientist Julian Osborn. You’ve rarely seen him this way before. Whether it entirely suits him is relatively beside the point. Gene Kelly and Judy Garland would follow in a pair of uncharacteristic departures in Inherit the Wind (1960) and Judgment at Nuremberg (1961).

Whereas the source novel apparently laid out who was to blame, the film develops a level of senselessness because no one — even those holding the highest clearance levels — seems to know how the tripwire was set off. They can only speak to their current reality. It makes an already disturbing situation a little more unsettling since there is a sense of universal ambiguity.

The questions linger. Might it have been an accidental mistake leading to the annihilation of our entire world, people all but expunged from the surface of the earth? It’s a chilling thing to begin admitting. Julian (Fred Astaire) is forced to acknowledge he doesn’t know.

It could have been some bloke who thought he saw something on a radar screen knowing if he hesitated his people would be obliterated. If this were the case, he would have only succeeded in setting off the dominoes. In fact, this nearly happened in real life one fateful day on September 6, 1983, to Stanislav Petrov, though he chose to wait, and it proved to be a faulty signal from his equipment.

It’s evident mutually assured destruction is a horrible system to wager on. And once you are past the point of no return, the apocalypse is a horrifying entity if there is no sense of hope. Most films must choose between inevitable doom versus some kind of hope.

In the waning days, we are antsy for finality, and it makes you realize just what the circumstances bring out. Waiting around for the end of the world sounds awful. And yet On The Beach manages to land the dismount even if the interim is slow-moving. True, there aren’t a flurry of events and there are a few asides — like Astaire winning the Grand Prix — which feel slightly superfluous to an impartial observer.

However, again, some kind of statement is being put to the fore, more nuanced than we might initially give it credit for, if not altogether succinct. It’s not simply an alarmist diatribe but there is a sobering urgency to it. The film foregoes the austere religiosity of the street preachers for something perceived to be much warmer.

Ava Garner standing on the shore, kerchief waving in the breeze, watching the receding figure of Gregory Peck on the deck of his sub is the movie’s indelible image. We need people around us to love and be loved by. Of course, some ill-advised individuals (myself included) live their everyday lives just waiting around for something. Hopefully, it doesn’t take nuclear devastation to kick our lives into overdrive.

3.5/5 Stars