I hope my analogy does not get misconstrued, but A Patch of Blue plays like a sublime fairy tale. It’s set in New York, a city that often feels as much of a visual fabrication made out of magic and myth as it is a real place anchored in time and space. Here is the very same world that exists in the Breakfast at Tiffany’s or other such pictures.

Shelley Winters is at her nastiest and most acerbic as a street tramp Rose-Ann. An evil “stepmother” if you will, because she and her daughter are on a first-name basis. Aside from that, you’d hardly realize they’re kith and kin. Because you see our cinematic cinderella, Selina D’Arcey (Elizabeth Hartman), is blind thanks to a violent altercation in her childhood and is now resigned to spending most of their time locked up in the shabby apartment.

Wallace Ford, bless his soul, is Ole Pal and though his heart might be in the right place, he’s not much used to the world because he spends most of his waking days home from work griping at the insufferable Rose-Ann or going out on the town to get royally plastered.

When Selina’s not slaving away at chores, she’s stringing beads together for mere pennies. Otherwise, she’s considered useless. She’s blind after all. It’s hardly a life at all. At least, that’s what the world around her seems to suggest and any minor pleasure like an afternoon in the park feels more precious to her than gold.

It’s in this said park where she first meets Gordon Ralfe (Sidney Poitier). If we wished to describe him, you could highlight any number of salient characteristics. He’s tall, handsome, and intelligent. He works the night shift and he has a brother (Ivan Dixon) who’s training to be a doctor. He’s also black…

But Selina cannot recognize or know any of this during their first encounter. Instead, she learns about him through his actions and words. Rather than being an impediment to their connection, somehow it provides the most sincere indications of human affection. She finds him to be kind and patient in a manner she has rarely experienced.

In this first encounter, she’s dumped her precious beads all over. She can’t possibly gather them together again and so we have an effortless meet-cute. For all we know, Gordon appears at her tree, but whatever the means — fate or happenstance — the film is never the same again. The metaphor of this movie is evident even for those who’ve never seen it. The cliche that “love is blind” is made quite literal because, for young Selina, that’s what happens. She falls in love for the first time.

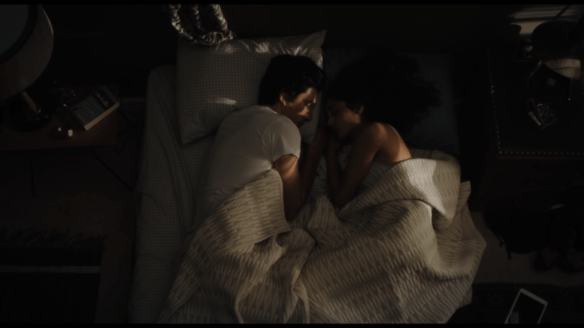

Guy Green does not employ altogether flashy filmmaking notwithstanding some fitting match cuts, but this leaves ample space for his narrative focal points. There’s something undeniable blooming between Hartman and Poitier making this movie a tender slice of romance brimming with sincerity.

Poitier empowers her in a way no one has bothered to before, and it’s an awakening of the world around her even as her sense remain attuned to everything. Though Poitier isn’t necessarily stretched beyond his limits — he’s perfectly at ease being a benevolent guide — his customary affability and charm feel infallible at this point.

True to form, he comes back in subsequent days to check in on Selina, providing her sunglasses to cover the scars on her face. Another day he offers her a can of pineapple juice, which she takes with relish. He broadens her horizons further by traveling together on the crosswalk for pastrami at the local delicatessen and then to pick up his groceries.

To us, these seem like mundane tasks, and yet for Selina, these are such generous acts because someone has taken the time for her. And though she is mostly unawares, there is a sense that in 1965, just there being together, existing in the world, and taking part in life together, is a meaningful act of solidarity if not total rebellion against prejudicial behavior. At its most fundamental level, it courts these ongoing themes of friendship and tolerance.

Most importantly, it is Gordon who rescues her from the pit of despair and the vengeful jowls of Rose-Ann once and for all. Remember, it is a fairy tale — Poitier acts as the fairy godmother whose job never has enough contours for us to really know what he does; he appears when he is needed most. His performance is matched by the agreeable whimsy of Jerry Goldsmith’s score dancing softly in the background. It can end no other way even as this adolescent girl’s life still hangs in the air partially unresolved.

Although the words have been echoed many a time, it does seem like Selina comprehends Dr. King’s incomparable words in their totality. Because in her mind’s eye and in their day-to-day actions, she has no difficulty judging Gordon, not by the color of his skin, but by the content of his character.

It’s another sentimental picture and you can rail against it, although I’m predisposed to enjoy its quiet bounties. Even compared to a more high-profile option like Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, there’s something unostentatious and rather attractive about this movie. It has Poitier’s sense of decency and there’s a message of tolerance, but the scale feels wonderfully mundane. So, perhaps it’s a realist fairytale.

4/5 Stars