We’ve been doing a rather casual retrospective on the films of George Sanders and as part of the series, we thought it would be fitting to highlight three more of his performances. They run the gamut of literary adaptations, fantasy romances, and medieval yarns. Sanders remains his incorrigible self through them all, and we wouldn’t have him any other way.

Picture of Dorian Gray (1945)

“Lead us not into temptation, forgive us our sins, wash away our iniquities”

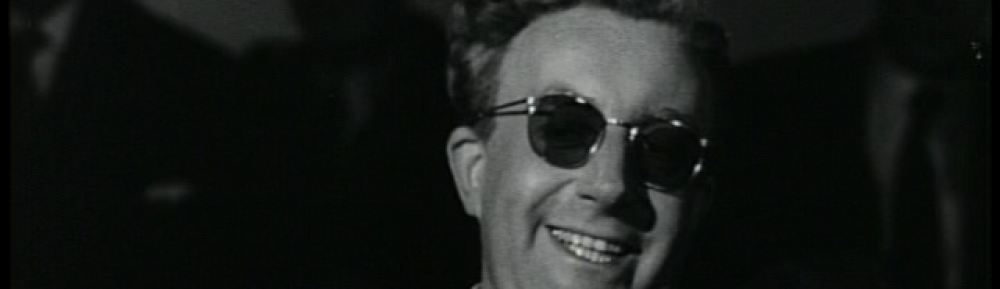

Whether you say he cornered the market or simply got pigeonholed, George Sanders could always be called upon to play snooty Brits bubbling with wry wit and aristocracy. His Lord Henry Wotton is certainly wanton — an incorrigible influence on many a man — and his latest acquaintance becomes Dorian Gray.

Hurd Hatfield is the picture of handsome youthfulness, dark and aloof, though his piano playing leaves much to be desired. His reputation must precede him and perhaps an actor with greater gravitas could have done more with the part. Hatfield feels generally inert and uninteresting. Over time, it’s hard to confuse his distance with inscrutable mystery.

The primary object of his desire begins with Angela Lansbury, an entrancing tavern singer with an equally gorgeous voice to go with it. Lansbury and then Donna Reed (his second flame) both deserved better, at least in their romantic lead if not the roles they were given.

It’s a quite loquacious film thanks in part to Sanders, who always has a cynical word for every situation and thus lays the groundwork for Dorian’s total immersion into hedonism.

The movie must work in mood and tone because there isn’t much in the realm of intemperate drama, and for some reason I found myself crying out for something more substantive than elliptical filmmaking. Whether it was merely to assuage the production codes or not, so much takes place outside the frame, which can be done artfully, and yet the distance doesn’t always help here.

The impartial narrator discloses Gray’s internal psychology to the audience as he’s perplexed by his evolving portrait — the lips now more prominently cruel than before. The ideas are intriguing in novel form in the hands of Oscar Wilde. Here it’s all rather tepid and not overtly cinematic watching a man traipse around his home tormented by his own inner demons.

It’s easy to contrast them, for their exploration of warring psyches and the duality of man’s morality, but this is not Jekyll and Hyde. However, on a fundamental level, I must consider my own criticisms because this is a story about pride, narcissism, and the selfish roots of evil in the human heart. They can be unnerving as we consider the portrait that might be staring back at us.

I find it a drolling, monotone movie other than the inserted shots of color that shock us into some knee-jerk reaction. It’s made obvious there’s a moral leprosy eating away at Dorian and the ending showcases much the same, doing just enough to hammer home the core themes of the story in a rousing fashion. Though your sins be as scarlet, I will wash them white as snow. It’s possible for the portrait to be remedied, though not without consequence.

3.5/5 Stars

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947)

“Haunted. How perfectly fascinating!”

If you don’t love Gene Tierney before The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, surely you must adore her afterward. She’s totally her own person; strong but not unpleasant thanks to her ever-congenial manner. She has immaculate poise and knows precisely what she wants.

Even in her mourner’s outfit in honor of her late husband, she has a regality drawn about her, vowing to leave his family and take her daughter (Natalie Wood) and their housekeeper Martha (Edna Best) to carve out a life of their own.

The film has a score from Bernard Herrmann post-Citizen Kane and pre-Vertigo that’s warm, majestic, jaunty, and frantic all at the precise moment to counterpoint Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s rather peculiar take on a romance film.

I realized an appeal for the picture I had never considered before. I find old haunted house movies, aside from those played for comedic effect, mostly overwrought and uninteresting. And yet even this early on in the lineage, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir effectively subverts the expected conventions.

Instead of merely being frightened off by the specters in an old seaside haunt of a deceased sea captain (Rex Harrison), it becomes her pet project. She’s intent on making it her home because she’s an obstinate woman — a descriptor she takes as the highest of compliments.

It’s pleasant how their immediate distaste and ill-will soften into something vaguely like friendship (and affection). They take on a literary voyage of their own as she helps transcribe his memoirs and vows to get them published for him.

George Sanders — always the opportunistic ladies’ man — shows up with his brand of leering, if generally good-natured impudence. In this case, he’s living a double life under the beloved pen name of Children’s book author Uncle Neddy. If his introduction seems sudden, its purposes quickly become evident. He is a real man of flesh and blood. It only seems right that Mrs. Muir makes a life for herself with him…

It’s curious how both men evaporate around the same time: one out of sacrifice, seeing her happy in reality, and not wanting to complicate her life more. The other’s gone because, well, he’s a cad. For those fond of Rex Harrison, it’s rather a shame he is absent from much of the picture, but this is by design because it is his very absence — this perceptible passage of time developed within the movie — that allows for such a meaningful conclusion.

It’s what the entire film builds to and between the rapturous scoring of Hermann and the simple but efficient special effects, it allows them to walk out together arm in arm as they were always meant to be. If they are apparitions, then at the very least they are together again no longer separated by chemistry, mortality, or anything else. These themes have been melded together innumerable times before but rarely have they coalesced so agreeably.

4/5 Stars

Ivanhoe (1952)

As a child, Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe always lived in the shadow of Robin Hood. The same might be said of this movie and The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood from years prior. By now Ivanhoe is both a feared and beloved mountebank and although late-period Robert Taylor is a bit old for the part and removed from his matinee idol days, it’s easy enough to dismiss.

Taylor and Errol Flynn were both heartthrobs around the same time. Now a generation later he looks a little weathered and threadbare for his tunic though he proves stout-hearted enough. Joan Fontaine also effectively replaces her own sister as the guiltless romantic interest.

However, there are some other intriguing elements I would have not expected of the film. It becomes a fairly robust dialogue on anti-Semitism and the relationship between the Jews and the Gentiles. We always think of British history or this particular period as a war merely between the Saxons and the Normans. Here we are met with a bit more complication.

Ivanhoe must play the rebel in the absence of his beloved King Richard, but he is also called upon to be a friend to the downtrodden even those of a different religious faith. In the moments where he’s called upon, he’s an unadulterated hero, and it’s all good fun watching him bowl over his rival knights like a row of five bowling pins. However, this is pretty much expected. It gets far better when he’s faced with mortal wounds in the wake of a duel (with George Sanders of all people).

Both Elizabeth Taylor and Joan Fontaine stand by ready to dote over him. The ambush by the Normans sets up a rousing finale every lad dreams about. Because my old friend Robin of Locksley comes to their aid prepared to lay siege to the enemy’s castle. Meanwhile, Ivanhoe leads a rebellion on the inside, freeing his friends and stoking a fire to smoke them out into the open.

Watching the choreographed craziness full of arrows and swords, shields, and utter chaos, I couldn’t help relishing the moment because we feel the magnitude of it all being done up for our own amusement. And it is a blast. Regardless, of the romantic outcomes, it’s a fairly satiating treat; I do miss the age of Medieval potboilers.

3.5/5 Stars