“I like you. You’re a nice monster.” – Chance Wayne

“Well, I was born a monster.” – Alexandra Del Lago

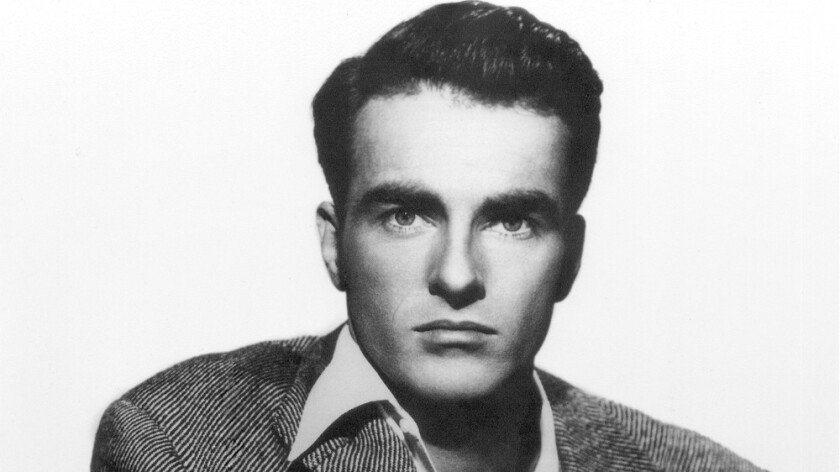

In this interchange between Paul Newman and Geraldine Page, I couldn’t help adding my own connotations. Alexandra Del Lago was born a monster. Chance Wayne is a self-made one. If anything, his environment has turned him into the self-serving creature he’s become. They are both looking to use one another, and they are not alone.

Although Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is the more high-profile entry, the points of connection with The Sweet Bird of Youth are too many to ignore. It’s yet another Tennesse Williams play directed by Richard Brooks for the screen, albeit neutered by the Production Codes of some of its controversy. This is hardly a new phenomenon.

Once more we have a sweaty, hot-blooded showcase for Paul Newman playing opposite a powerful Southern patriarch (in this case, Ed Begley) and other cast holdovers include Madeleine Sherwood.

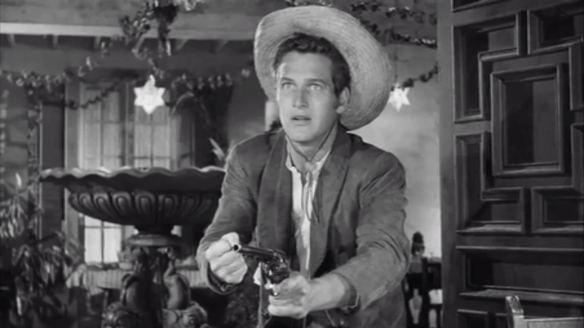

The premise is simple enough. Chance Wayne (Paul Newman) returns to his hometown of St. Cloud, Florida as a big shot. At least this is the illusion he looks to promote as he sets up in the local hotel.

His companion is a fading movie star plagued by her self-medication and neuroses as she tries to stave off the advances of a has-been career. He has elected himself her PR man — stirring up headlines she doesn’t want — to benefit his own career no less. He fluctuates between opportunism, blackmail, and virile charisma all in the name of getting himself said break.

If Alexandra Del Lago, masquerading incognito as the Princess Kosmopolis, is his Norma Desmond, he is a sleazy sellout looking to wheedle his way into any amount of fame. Chance is looking to use her clout for all its worth because her seal of approval still means something in the industry. Alexandra need only say the word to the Louella Parsons and Walter Winchells of the world, and this nobody could hit the big time.

While Del Lago is on the way out, Williams flips the script with another revelation; Chance is on the way out too — if he ever arrived at all. Because years of striving have found him little success. He believed in the pie in the sky ideas of the local institution: Tom Boss Finley (Ed Begley). Every man can hit the jackpot if he tries hard enough. He didn’t stop to consider Hollywood is a crazy land with walls all around it. All the failures are kept on the outside looking in until they grow old and undesirable.

On Sunday morning the bells ring — it’s Easter, after all — and Alexandra rises from her bedroom suite positively reborn! Chance goes off to the church. The other leg of his personal fantasy involves running off with his sweetheart, the aptly named Heavenly (Shirley Knight). But her daddy, Boss, and the skeevy Tom Finley Jr. (Rip Torn) are bent on keeping her away from Chance. They aren’t opposed to physical violence as Tom Jr. has a group of mobilized hoodlums called the Finley Youth Club at his disposal.

Because if Boss Finley is a pillar of society and a Sunday morning Christian who promotes his virginal daughter and denounces communism and other prurient attacks on the American way, he’s cracked at the seams himself.

His own daughter is skeptical of his deep-seated hypocrisy. Even before his dear departed wife passed away, he kept Ms. Lucy, a lady waiting, well-compensated at the local hotel. It’s the duplicity of this brand of sing-song Southern hospitality with an undercurrent of venom. Although the South by no means has a monopoly on this type of behavior.

If there is anyone to feel sorry for at this point, it might be Del Lago and yet Page ultimately regains her dignity as her frailties fade away long enough for her to see Chance for what he is: Just a name with a body. She’s known many of them before. Men led by a chain for want of fame and stardom only to be kept down.

If Newman is supposed to be an archetype of a callow young man, he has far too much charm and smarts to come off as a Yokum totally duped by Boss Finley’s grandiose talk. Regardless, he and Alexandra each have their own private hell to go to. Where can this story go but down?

In a word, there is a hopeful ending for both of them. It doesn’t aim for the jugular of tragedy. It’s not aiming for the grandest heights of southern gothic melodrama, and so it settles for a minor note. If the sweet bird of youth passes you by, it’s a matter of making your peace with it — finding peace in something else.

I couldn’t help focusing on the hymn playing in the background of the final scenes. These folks have probably sung the words countless times only to have them bounce off the walls of their hearts. Its lines go like this:

Not the labor of my hands

Can fulfill Thy law’s demands;

Could my zeal no respite know,

Could my tears forever flow,

All could never sin erase,

Thou must save, and save by grace.

Rock of Ages cleft for me

Let me hide myself in thee

3/5 Stars

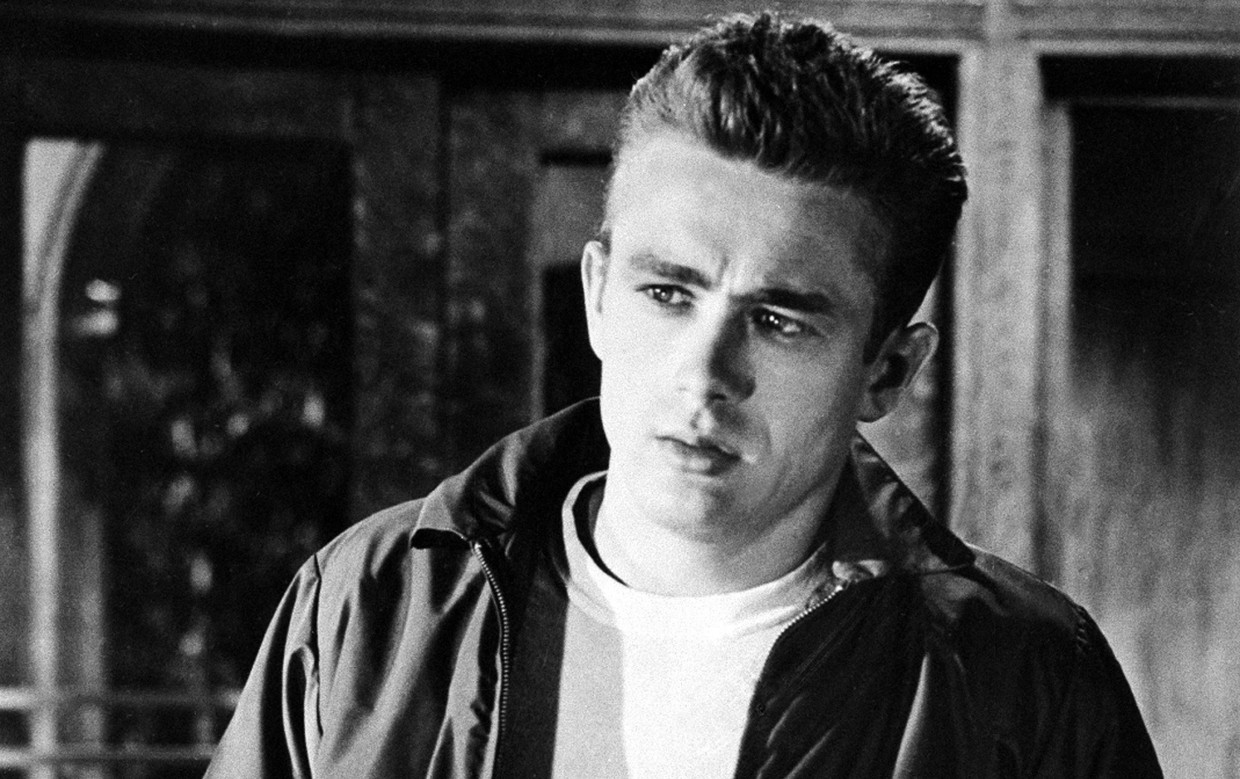

As it turns out, Paul Newman’s a real barn burner. His family name is synonymous with conflagrations and it’s a great entry point for a character, in this case, a drifter named Ben Quick who’s run out of town by the local judge.

As it turns out, Paul Newman’s a real barn burner. His family name is synonymous with conflagrations and it’s a great entry point for a character, in this case, a drifter named Ben Quick who’s run out of town by the local judge.