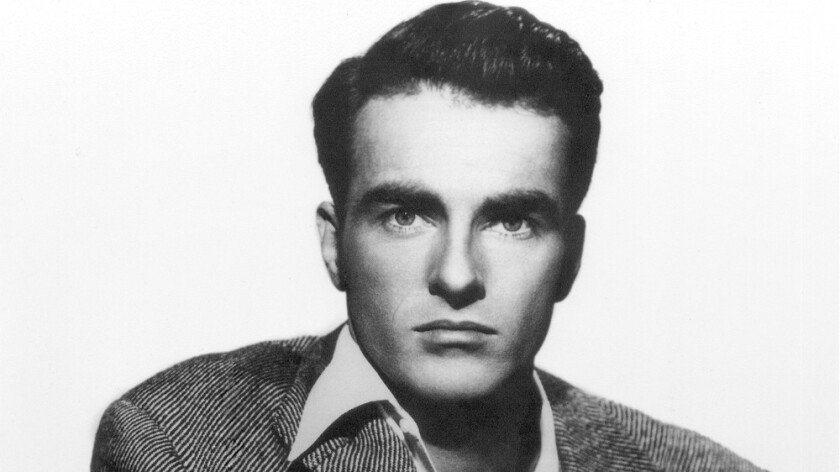

The manner in which Garfield is lit in the opening scene is striking. We don’t know the reason yet, but there’s a prevailing angst and discontentment spelled out over his face. It sets the tone for the rest of Jean Negulesco’s swelling drama Humoresque.

I’m not sure if it’s curious or not how John Garfield, the man who made a break for himself with Golden Boy on the stage, did a boxing movie — a story of brawn — and then did a violin picture — one focused on art. It’s as if he broke off in both directions thereafter because these are the two dualities at the core of Clifford Odet’s original work.

At first, I didn’t know who wrote Humoresque, but these themes made it ridiculously simple. Yes, Odets obviously wrote this too. It inhabits the same world and gives Garfield a similar context — one that he knows firsthand.

On one fateful birthday, Paul (Robert Blake) wants a violin. His father (J. Caroll Naish) holds firm and won’t buy it for him, but he’s not a bad man. Just a poor shop owner. However, his mother (Ruth Nelson) wants to cultivate her son’s talents opting to buy him the extravagant present in the hopes he will make good. Instead of playing ball, he stays home and practices, eventually growing into his own. He literally turns into John Garfield.

At first, Oscar Levant featuring in this movie feels a bit like Hoagy Carmichael in the Best Years of Our Lives. They don’t necessarily fit with the continuity of the drama, but we have enough grace to forgive them and enjoy what they bring to the table. To his credit, Levant evolves into more of a snarky mentor before coming into his own as Garfield’s quipping second banana.

Of course, that’s what he always seems to be, but piano playing aside, that’s what he was always so good at, ready with a remark for every situation. He’s one of the singular figures. Naturally gifted in front of the camera, but also an astounding artistic talent.

Garfield also has some of the best fake instrument playing I’ve seen in some time. Isaac Stern is his stand-in, and yet they film Garfield in a way that feels especially tight, never fully breaking the suspension of disbelief. He feels like a virtuoso on strings. Levant, of course, needs no assistance.

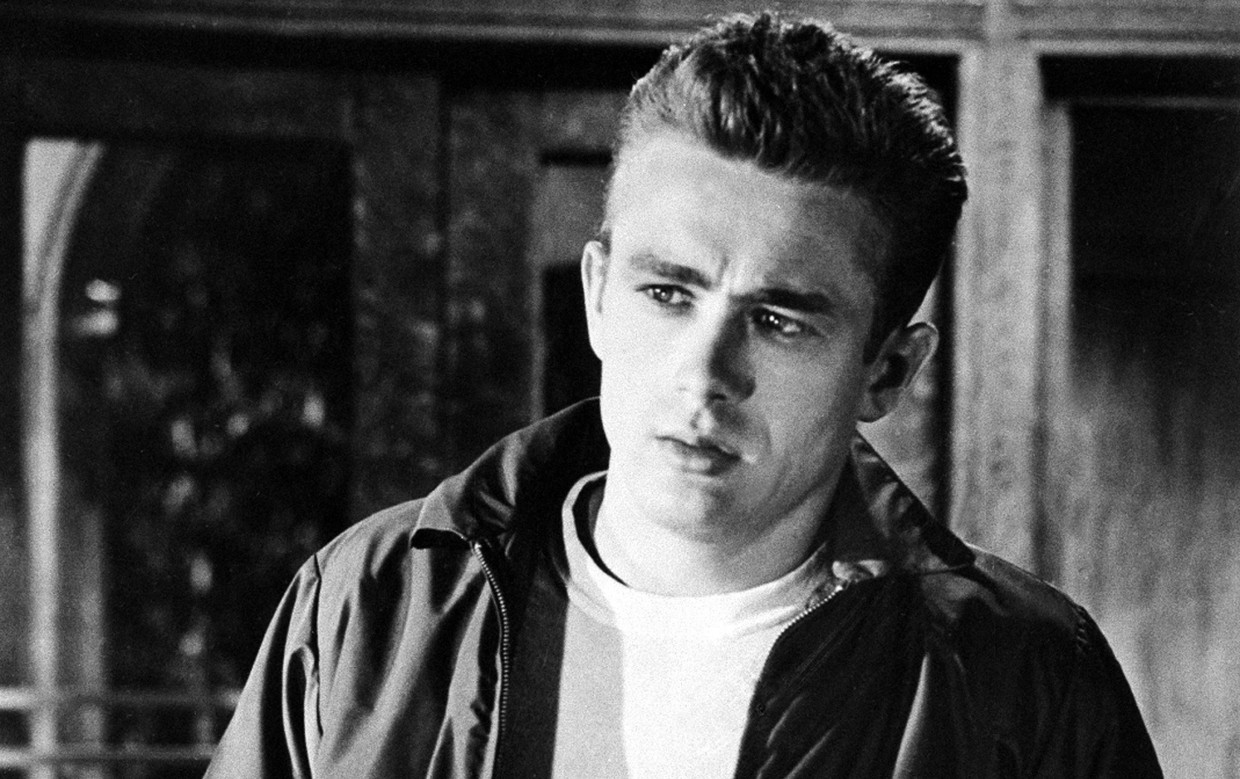

But we’ve held off long enough mentioning Joan Crawford. She was coming off her own success in Mildred Pierce from the year prior and during the ’40s and early ’50s, she would continue in a row of pictures that continue to bolster her reputation (ie. Daisy Kenyon, Sudden Fear). It’s no different with Humoresque.

She makes her ravishing appearance at a soiree. It’s Paul Boray’s coming out party with some real tastemakers. His first acquaintance is an older fellow, not unkind but passively resigned to his fate with a bit of wry commentary. This is Mr. Wright. She’s the woman at the center of it all: Mrs. Wright. Slightly tipsy, near-sided without her glasses, yet still alluring and swarmed by a host of other men.

They all fall away as she puts on her glasses to watch Paul play. She playfully rides him, and he fires right back. It sets the precedent for what their relationship will be, and we would expect nothing less from both stars.

Violin films are few and far between, but during Garfield’s first grand performance when everyone turns out from his family, including a local sweetheart, and then the social elite led by Crawford, the cadence of the scene is rather like a boxing film. You have the action, in this case, his fingers on the strings, instead of boxers in the ring, and then everything is made by the reactions from the crowd. They play in tandem with one another to add up to something richer than the sum of their parts.

The Garfield-Crawford dynamic really is appealing because they carry off such command of the screen. She calls him an obstinate man, but she’s hardly a pushover, and it makes their working relationship, with the suggestive romantic undercurrents, all the more intense.

There’s a cut from her seltzer water to the ocean surf that feels like an ellipsis in the story and their relationship. Otherwise, it doesn’t make much sense. Garfield is suddenly more forward in pursuit of her, although prior he was busy trying to ward her off. It’s analogous to his romp at the beach with Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice as the visual consummation of their romance.

Later, there’s a lovely introduction of an ice rink and the adjoining restaurant. It’s instant ’40s atmosphere, and Paul and the long-smitten Gina (Joan Chandler) sit waiting for the perenially tardy Levant. It leaves ample space for dialogue over their relationship, which, aside from a couple scenes and mild inference, is all but non-existent. What it suggests is the promise of an alternative life if Paul were to choose it. She is the good sensible girl his mama would love. But, still, there’s his music to think about…

In another packed-out hall, he plays again, and this time Mrs. Wright watches from the balcony. The camera lingers on Crawford’s face and closes in on her expression, with a look that can only be described as ecstasy washing over her eyes and lips. They can hardly be seeing this, and yet as the camera cuts to his mother and Gina in the cheap seats down below, their own faces fill with worry. Their intuition or the cinema fates are telling them Paul is lost, and he’s been taken over by other powers altogether. Something uncontrollable has taken over.

I’ve never taken much notice of Jean Negulesco, but here the artistry of the creators feels very much on display in the most intriguing ways. It pairs nicely with the motifs of Odett’s work dabbling in art and commerce and dreams versus pragmatism. Because these are often the forces that divide people when it comes to pursuing a life of art and then sticking with it. Boray finds someone to commission him even as he has plenty of his own private ambition.

There’s a perceptive change in his parents as well. His father becomes warmer and proud of his son’s talents in old age. Then his mother, who empowers and even coddles him, grows highly protective. She becomes wary of the company her son keeps.

Oddly enough, I never found myself totally detesting her. Because I see her point of view. She wants her son to have stability but also the space to pursue his life’s passion. As a divorcee and a different breed of woman, Helen strikes out on two accounts. But it’s not simply this. Ruth Nelson has a gaunt sadness in her eyes I could not get away from.

Even as his familial relationships shift with his newfound success so does his love life. Helen goes from mere patron to jilted lover. She doesn’t want their relationship to be business and formalities, and yet she’s “playing second fiddle to the ghost of Beethoven.” Paul’s first love is really his music.

In the final concert, Helen listens from her Malibu beach house. His parents have gotten upgraded to a box. Gina still sits by faithfully in the audience. But it’s all overshadowed by Crawford as she heads out to the shore. Her listless walk on the beachfront is perplexing. A man playing with his dog wanders into the frame, and it feels unexpected. Because she is in her own world overwhelmed by the music totally deluging her life at this moment in time.

I was mesmerized by the waves crashing around as we get fully submerged through image and score, immediately comprehending the weight of what is happening before us. The actual ending doesn’t rationalize or totally sugarcoat this story, but the words Garfield gets out can’t do anything to improve on the preceding images.

Humoresque feels like an uncommon movie. Its subject matter in this particular form is not often examined with this much detail, and John Garfield side-by-side with Joan Crawford makes for a tumultuous, rapturous, confounding melodrama. Try as I might, I can’t quite put it into words. It deserves music.

4/5 Stars