This is my Entry in the Classic Movie Blog Association’s Fall Blogathon Movies are Murder!

Although no one knew it at the time, Confidentially Yours would become the makeshift curtain call to Francois Truffaut’s career as he died of a brain tumor shortly thereafter. The movie in no way makes up for the works we lost out on, but there are some fitting summations worth appreciating. Truffaut cast his latest muse, Fanny Ardant, in the lead role — subverting the prototypical blonde Hitchocockian heroine.

Like her predecessors, Ardant is winsome and brave, whether in stage garb or a trenchcoat in the tradition of noir working girls like Ella Raines or even Grace Kelly. They’re capable of being both intrepid and alluring on screen as the dauntless motor behind the story.

It’s true the film’s plot, execution, and sense of style owe a debt of gratitude to Truffaut’s cinematic hero. Like Alfred Hitchcock’s film Stage Fright, Confidentially Yours covers murder and the performative aspects surrounding it.

There’s a kind of duality because Ardant is not only a secretary embroiled in a local murder, but also moonlights as a stage performer at night even as she dons various parts throughout the movie to aid in her detective work. Much of this fades away as mere pretense as we get deeper and deeper into the nitty-gritty world of old-fashioned noir.

Confidentially Yours boasts a brisk beginning befitting a more contemporary film: A man is brutally shot out at a pond, and there’s only one obvious suspect. Truffaut implicates his own star through the cut because the first image we see after a bloody murder by a faceless perpetrator is Jean-Louis Trinitnant walking back to his car. He sees a nearby car door left ajar, and he closes it before returning to his own vehicle and driving off. When the police come to question him later, he seems to slip up in his story.

Surely he’s a guilty party. He has motive. His wife was unfaithful, and now one of her many boyfriends is dead. What’s more, Trintignant plays him as a brusque character — he’s not winning any awards for likeability — and yet these are not the metrics for guilt and innocence as we’re probably already all aware of. To use a staid figure of speech, people are often more than meets the eye.

Also, there’s the question about fingerprints. He left them all over the crime scene. Either he’s an incalculable fool or there’s more to the story. Ardant occupies an unenviable position. She seems to be working for a guilty party, she’s given the ax by her embittered employer, and yet she still finds some compulsion to begin poking around.

She starts sleuthing, coming into contact with a melange of lawyers, policemen, and shadowy undesirables. It’s easy to get bogged down by what feels like an incomprehensible cascade of plotting, but isn’t this the point? It’s not the particulars but the means of getting there proving the most important, and Ardent is one of the most supernal vessels we could possibly imagine. Somehow she seems like the predecessor of Hayley Atwood with the poise of Isabella Rossellini thrown in for good measure.

One of the film’s other lasting assets is the gorgeous monochromatic tones of Nestor Almendros. It proves to be an immaculate act of mimesis plucking the movie out of the ’80s and allowing it to drift into that timeless era of yesteryear that only lives in the thoughts and recollections of our elders who experienced the world and dreamed in black and white.

As her employer stays mostly anonymous behind his shuttered-up storefront, Ardant becomes his hands and feet, searching out a ticket taker at a movie house, and then leading to a nightclub. Later, she looks to infiltrate a prostitution ring using all her wiles to spy out the window of the lavatory. Eventually, her tenacity is rewarded, and she does what the police seem incapable of through normal channels.

Truffaut for me will always be one of the most ardent cinephiles with the likes of Martin Scorsese and a handful of others. Men who often made fantastic, exhilarating films, but not out of a debt to mere craftsmanship or technique. It’s so palpable how much they love these things. Their films can’t help but smolder with a boyish fanaticism they were never quite able to shake.

Scorsese still seems to make a young man’s movies with an old man’s themes, and even though we lost Truffaut at 53, hardly in the autumn of his life, he had some of the same proclivities. He loves the genre conventions of old. There’s almost a giddy enthusiasm to do his own Hitchcock movies like Shoot The Piano Player, Mississippi Mermaid, The Bride Wore Black or even this final entry.

And yet on the other end of the spectrum with the likes of Antoine Doinel, The Wild Child, and Pocket Money, he managed to tap into these deep reservoirs of emotional soulfulness. It feels as if adolescence is incarnated and imbued with empathy by someone who never quite left that life behind.

Since Godard still manages to have an influence on cinema culture as one of the revered old guard throughout this century, it remains a shame we lost Truffaut so prematurely. He still lives on through his films and the admiration of others like Steven Spielberg, but I do feel like if he was still alive today, his love of the movies would be equally infectious if not more so. I suppose it makes the catalog he left behind all the more important.

I didn’t consider until this very moment, but with “confidentially yours” the director is leaving us with his final valediction before signing off. It seems fitting his complementary farewell drips with the pulp sentiments he relished starring a lady whom he loved.

4/5 Stars

Note: This review was originally written before the passing of Jean-Luc Godard on September 13, 2022.

Francois Truffaut has a knack for understanding children in all their intricacies. One suspects it’s because he’s never really grown up himself. He is a child at heart with even his earliest films of the Nouvelle Vague channeling the joy and the passion of a younger individual.

Francois Truffaut has a knack for understanding children in all their intricacies. One suspects it’s because he’s never really grown up himself. He is a child at heart with even his earliest films of the Nouvelle Vague channeling the joy and the passion of a younger individual. I didn’t think about it until the movie began, but the only person I’ve ever known to only go by the initial of their last name was for the sake of keeping their anonymity. If you’re a nobody, it doesn’t matter who knows your name.

I didn’t think about it until the movie began, but the only person I’ve ever known to only go by the initial of their last name was for the sake of keeping their anonymity. If you’re a nobody, it doesn’t matter who knows your name. The Wild Child (L’Enfant Sauvage in French) is based on “authentic events,” as it says because Francois Truffaut became fascinated by a historical case from the 1700s. A feral boy was discovered out in the forests and then taken under the tutelage of a benevolent doctor.

The Wild Child (L’Enfant Sauvage in French) is based on “authentic events,” as it says because Francois Truffaut became fascinated by a historical case from the 1700s. A feral boy was discovered out in the forests and then taken under the tutelage of a benevolent doctor.

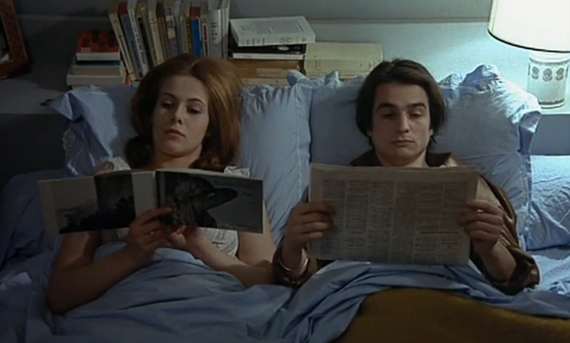

There might be an initial predilection to call The Soft Skin Francois Truffaut’s most conventional film to date, but for me, it shows at this fairly early point in his career he seems to have grasped the main tenets of traditional filmmaking. Because his first films are full of life, energy, and idiosyncratic verve that easily charm their audience but here we see a film that in most ways looks like other classic works, well constructed and still quite engaging. Because within this very framework Truffaut is able to play around with issues that in themselves are still quite compelling. Love, intimacy, infidelity, and the like. Even with familiar names like Truffaut and Raoul Coutard, it feels very un-Nouvelle Vague. And that’s okay.

There might be an initial predilection to call The Soft Skin Francois Truffaut’s most conventional film to date, but for me, it shows at this fairly early point in his career he seems to have grasped the main tenets of traditional filmmaking. Because his first films are full of life, energy, and idiosyncratic verve that easily charm their audience but here we see a film that in most ways looks like other classic works, well constructed and still quite engaging. Because within this very framework Truffaut is able to play around with issues that in themselves are still quite compelling. Love, intimacy, infidelity, and the like. Even with familiar names like Truffaut and Raoul Coutard, it feels very un-Nouvelle Vague. And that’s okay.