It was another strange year at the cinemas, but there was a lot to appreciate.

Here’s a list of some films I enjoyed in 2022 and you might too. I’ll probably be releasing some other capsule reviews at the beginning of the new year. Let me know what you think!

No Bears

Of late I’ve been considering the films that leave an inexorable impact on me. Certainly, they entertain and compel us in some fashion as a viewer, but oftentimes the best, most daring projects utilize the medium of film in some unprecedented way – using its limitations and reflexivities to birth something new and meaningful into the world. I can think of few recent films fitting this category better than No Bears.

German director Werner Herzog always likened the filmmaker to a resourceful vagabond able to pick locks and prepared to spend a night in jail if it means getting the right shot. At least in his estimation, there’s such a thing as good trouble. Director Jafar Panahi takes this to his own extreme as he’s had his own well-documented run-ins with his home country of Iran, which has previously forbidden him from shooting movies. Given Panahi’s mentorship with the revered Abbas Kiarostami, it’s difficult not to draw a line between their work. In something like Close-Up (1990) we are dealing with the almost imperceptible dividing lines between filmed fiction and reality – that which is staged and fanciful and what we might term documentary.

It does seem like Panahi is somehow dabbling in a fiction willed into reality. But it’s more unnerving than we can imagine even if he’s well aware of the ground he’s treading. His “fictionalized” version of himself struggles to direct a movie remotely across the border in Turkey, while he must remain in the country, dealing with woeful internet connections and kerfuffles with the local populous. We recognize a world around him divvied up and made insufferable by boundaries, borders, rules, and traditions so much so that words and reason seem arbitrary and even religious rites and oaths lack any kind of inerrancy.

He’s currently under arrest by the Iranian government and the dark irony is bracingly apparent. There’s both a bravery and a brazen cavalierness to it all. No Bears contends with both the cultural hypocrisies and the ethics of such a tradition as moviemaking. Sometimes things aren’t meant to be captured and held captive by a camera. Sometimes the camera captures nothing – only the innocuous and the quotidian – still, that doesn’t stop it from being feared.

Decision to Leave

Decision to Leave is a transfixing tale meditating on the voyeuristic nature of both love and murder. But it’s not just about these themes; it’s about how romance and murder are cut together and potentially become inseparable within this indecipherable realm of the police procedural. It’s certainly not a film without precedent when it comes to the subject matter. It focuses on a detective (Hae il Park) investigating a crime with his primary suspect being the Chinese wife (Tang Wei) of a Korean businessman — a man who recently died in a climbing accident.

It works in the same spirals as Hithcock’s Vertigo as we watch the detective become more infatuated with this enigmatic cipher of a lady. His vocational obligations of interrogation and surveillance fluidly become a personal obsession. It walks this nervy tightrope between bleak romantic drama and dark noir while utilizing exquisite cuts between the past and the present with a precision fluidity bringing to mind something like Antonioni’s Passenger. We are obviously in able hands as our protagonist struggles to stabilize after being sent reeling by the effects of this mesmerizing woman.

Director Park Chan-wook taps into a great many elements that have made fatal noir romances a lasting pillar of crime cinema including entries like Memories of Murder and even Gone Girl. But I became particularly fascinated with how it dealt with this cross-cultural relationship. Somehow Tang Wei perfectly modulates her performance between the innocent heroine and perceived aggressor, and the space is muddied by all the ambiguities that come with interactions totally lost in translation. It weaves together a genuinely tragic romance on an emotional plane full of pathos with a mystery thriller ratcheted up by immense tension.

But there’s also a poeticism to the movie going beyond mere visual aesthetics. These motifs probably deserve further consideration – I’m thinking especially of the juxtaposition of imagery between the mountain and the sea – even as the film itself has much to offer a ready audience. The subsequent ending exhibits the fated doom deeply entrenched in the noir tradition. Otherwise, on a broader scale, Korean cinema continues to offer the world stage numerous dark, surreptitious delights. This entry just happens to be a canny hybrid of all of Park Chan-wook’s earlier predilections ready for consumption.

Aftersun

You will not find anything spurious or mean-spirited here. In its place is a tableau built out of an intricate array of personal observations. Charlotte Wells has effectively harnessed one of the most powerful attributes of film: its capacity to capture time in a bottle both refracted through our memories and the frames of celluloid space. Many of us are familiar with home movies. Our fathers may have captured them or we gathered our friends together to make some two-bit swashbucklers (even Speilberg’s Fabelmans is deeply indebted to them).

But I was also reminded of this year’s 3 Minutes A Lengthening. Because Wells has dealt with time in a similar manner. In honing in on a moment — this seemingly mundane weekend between a father and his daughter — the director has collapsed a relationship down to its essence in a way most of us can intuitively understand. For many of us, time has probably gotten away with us, and we look back on childhood with warmth if not a glassy-eyed longing.

Paul Mescal leads the father-daughter tandem with a kind of composure that feels ageless and still constantly unfathomable. He is a man caught between fatherhood and a life he seemingly lost as he navigates his own insecurities through meditation and Tai Chi. What makes it work is how present he seems in the moment. He’s not a perfect father by any means, but he seems like a genuine one – he desires to be available to his daughter. However, the bountiful shared history only works if he has an able foil, and Frankie Corio has a lucid precociousness we see in all the finest child stars – exuding naturalism directors can only dream of.

Because her point of view is so crucial to this piece. Rather like a mundane Fallen Idol (1948), it is through her eyes that we must both mediate between past memories and the present. We appreciate her childlike gaze and also the ruminations of her older avatar. In truth, we are all navigating this in between amidst the past and present, the living and the dead. It might seem drastic but surely this is what movies are for – allowing us to grapple with these very things in the most poetic way possible.

The Fabelmans

It’s easy for films about a filmmaker’s own experiences to come off a bit narcissistic, but what better way is there to write what you know? In the case of Steven Spielberg, he feels like a generally beloved figure and so this act of self-reflection feels as much like a gift to the audience as it is a visual autobiography. In other words, I doubt many will begrudge him for taking the opportunity. Many have pointed out that Spielberg’s films always have some semblance of divorce and fractured families at their core.

Upon watching The Fabelmans, my mind drifted to the interview Speilberg did with James Lipton for the Actor’s Studio. Lipton connected how in Close Encounters of a Third Kind, humanity communicates with the aliens by making music on their computers – subconsciously Spielberg seems to be tapping into his childhood: His father the kind, pragmatic computer scientist, his mother the free-spirited artist. An entire oeuvre of movies would not exist without their influence and Michelle Wiliams and Paul Dano bring them to us with tender aplomb.

Late-period Spielberg has given us great period pieces like Lincoln and Bridge of Spies. For me, these lack the immediacy of his earlier works, and yet, again, I hardly begrudge him because there’s still a wide-eyed joy to each new project. He hasn’t lost that fervor and that’s even more evident when tackling his own family, though he’s now a more seamless technician than ever. In recreating many of his real childhood films, we recognize all the seeds of ingenuity, and it’s possible to see the invention plucked out of necessity.

Whether it’s crashing trains or school bullies, movies gave Spielberg a conduit to take control and gain mastery over what he could not fully comprehend. He’s warned, “Art will give you crowns in heaven and laurels on earth, but it can also leave you lonely.” It’s a heady portent even as he watches his parents’ relationship disintegrate in front of his eyes and through celluloid (It felt like a far more heart-wrenching version of Antonioni’s Blow-Up).

Still, for any cinephiles or budding directors, it’s easy to see this man (or boy) as a kindred spirit. It’s like a code – carbon dating his childhood by the movies he watches – and sure enough, we see him enthralled by John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). What’s more, in an inspired piece of casting, the old master makes a cameo. It depicts another piece of mythology deeply steeped in Spielbergian lore. As they say, the rest was history. Jaws, E.T., Indy, Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List and so many more. What a lineage to celebrate. I feel like I know him better than ever before because he has done something far from self-aggrandizing; he has let us in with a level of profound transparency.

Banshees of Inisherin

I recall watching a documentary called Godspeed about an American priest who was transplanted to Ireland as his new parish. It was a culture shock because outside of the hustle and bustle of the big city or even comfortable western suburbia, he was forced to live a very different sort of life – one of very close proximity. They always say you can’t pick your family, but in a tiny society like this, you can’t well pick your friends either. That story focused on how such a lifestyle forces you to be known by those around you.

Somehow Martin McDonough deals in some dark inverse of this. What if the person you know most in the world – the one you call your dearest companion and drinking buddy – now wants nothing to do with ya’? What are you supposed to do and how do you react in these circumstances? Banshees of Inisherin is a fable and a character study relying mightily on the written wit of McDonaugh’s bleak quill, and the quibbling, deeply heartfelt performances of Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson.

The panoramas of Ireland are right out of a storybook like we expect them, but this is a harsh, acerbic tale, which also happens to be astutely funny. I’ve not always been a ready audience for the Irishman’s work, but somehow I appreciated this far more than I expected. Sometimes being kind is far more potent than leaving a creative legacy – sometimes that is the legacy – and yet McDonough doesn’t stop there. He leaves his feuding rivals to their own devices. And we are left to pick up the pieces (including a ghastly array of severed fingers).

My own first name is Irish Gaelic and with that comes a modicum amount of pride. It feels alive and pulsing with all sorts of history I cannot begin to articulate. Because McDonough and the majority of his cast have Ireland in their blood, somehow it adds profound layers to this story. It’s as if they understand the intimacy and pain of this landscape in almost unknowable ways. Their world is full of rich lineage and a fierce sense of identity which is as much about community as it is about strife and civil discord. It really does feel like a constant battle.

Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio

It plays like the anti-Disney version of Pinocchio, and it’s more than vindicated in its creative choices. There’s nothing sanitized or streamlined about any of its contours and though I have not seen the Robert Zemeckis version, the source material does seem to fit Del Toro more intuitively. It feels like it can be an earthier more generous version of the tale without saccharine sentiment. The beloved story is placed against the backdrop of 1930s fascism and this measured creative decision evokes something of Jojo Rabbit if not Fellini’s Amarcord, even as Pinocchio is generally a narrative of childish disobedience and ultimate redemption.

Pinocchio is created by Gepetto out of the tragedy of the war and although he’s a beloved creation, he’s a seemingly horrid little boy. To be a fully animated, living, breathing human being is to know the fallibility of the human frame and the depths of death and tragedy. It’s no coincidence Gepetto spends much of the movie toiling away to rebuild the crucifix for the local church. Here is a symbol of the need for absolution even as Pinocchio’s ever-growing nose is a glaring reminder of how often he falters.

As a child, I abhorred, not the Disney film, but Carlo Collodi’s original children’s book because Pinocchio is such a reprehensible tyke. Del Torro gets that right and his world is fanciful, but not while totally disregarding danger and ugliness. Because this is what the world of fairy tales was made for beyond tangible history and Mussolini. Fantasy sets up parameters for a space outside of our own that nevertheless deals with the most unspeakable and difficult issues that children know to be true so that within this context of safety, they might come to terms with them.

While there’s a talking cricket (Ewan MacGregor), a scowling monkey (Cate Blanchett), half-dead bunnies, and a warty behemoth of a leviathan, what really speaks to us are themes of friendship, fatherhood, and ultimately, sacrifice. As best as I can understand, this is the eucatastrophe Tolkien speaks about where all sad things become untrue.

Hit The Road

Hit The Road is probably the most genuinely funny movie I’ve seen and part of this is because of the dubious undercurrent. This unease goes unspoken for much of the story, but we recognize it’s there as something that has precipitated this entire journey. I found myself giggling all the way through because each of these characters feels so fully realized with all the quirks and idiosyncrasies we can appreciate even as they feel perfectly calibrated to gripe and annoy one another to no end.

The grousing father with his cast. A chatterbox son who elicits headaches. A mother with maternal instincts constantly worrying about her kids. And an older brother holding onto angst about his future. It’s true these are the markers of a family on a long road trip. But while it’s convenient to provide a comp like Little Miss Sunshine, Panahi is of his own mind and goes off toward a destination of his own design.

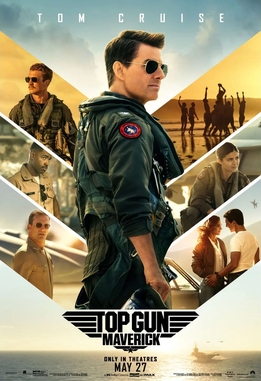

Rarely do I feel this genuine sense of danger while watching modern films, but whether it’s Tom Cruise’s stellar real-world feats in Top Gun or the societal backdrop of Hit The Road’s Iran, there’s a sense of unease – as if this film in its very conception is a marvelous act of daring expression. Later, the little boy recounts a scene out of the Batman movie where the Scarecrow uses “fear gas.” He’s disregarded by the adults because he doesn’t realize the real weight of his older brother going away.

Again, so much of this is ambiguous and these choices are important. There’s also the decision to shoot another crucial scene from a pronounced distance so our main players feel like mere comic specks on the canvass, but the humor is never far removed from heartbreak. I can’t get the image of the mother driving and singing at the top of her lungs with a forced smile on her face because it’s her only armor against tears. This movie melds both emotions so exquisitely; all that’s left is to marvel at the impact and be totally disarmed.

Saint Omer

There’s a necessity to Saint Omer’s opening sequences following a literature professor (Kayije Kagame) as she recounts to her class France’s post-war history of shaming female collaborators by shaving their heads for all to see. She makes particular mention of Marguerite Duras’s writing of Hiroshima, Mon Amour – how the author was able to turn these memories of ignominy into a kind of “state of grace.” These moments might feel like a digression, but as the story builds, they become the groundwork for the entire narrative placed before us by director Alice Diop.

Saint Omer has to be one of the most moving courtroom dramas I’ve witnessed in some time. It forgoes using the courtroom premise to build a contentious ever twisting thriller. Movies like this are often won in their grandstanding moments on the stand. Here there’s a completely different approach; this is mostly an understated character piece.

A French-Sengalese mother and grad student (Guslagie Malanga) is up on the stand for abandoning her 15-month-old baby. Her child eventually washed up on the beach dead. Given the gruesome circumstances, she offers measured, unblinking responses to every line of questioning. Her top almost blends into the wood paneling behind her. We watch as both her shortcomings and her tragedy are laid bare before us and slowly churned through by the pragmatic nature of the courts. The results are imprinted with all sorts of responses, both explicit and implicit, coming from witnesses, judges, jurors, and most stirringly the defendant’s lawyer. “We are all chimera,” she says.

As the proceedings march on, Rama, our literature professor and entry point, grows increasingly affected. She too is Sengalese, also in an interracial relationship, and she identifies deeply with this woman on trial, both for her relational shortcomings and the little indignities she faces. Nina Simone’s “Little Girl Blue” feels like the perfect summation for me in ways that can barely be articulated. This movie is slow, even plodding to my sensibilities, and yet I’m still trying to come to terms with it.

After Yang

Kogonada’s Columbus was a revelatory experience for me because not only did his exquisite work with The Criterion Collection translate to a gorgeous visual aesthetic, he seemed to make the movie I always wanted but had yet to receive. John Cho headlined a picture, and it was a movie about substantive issues. After Yang is a moving follow-up as the director takes a short story and turns it into grounds for how we consider issues of family and grief by way of Yasujiro Ozu.

In his future, Kogonada has created a definition of family in this multicultural world of ours, represented not by rigid uniformity but by vibrant individualism still bonded together by the human qualities of parenthood and care. I know it well and watching After Yang there’s an immediate kinship of a daughter who is grafted into this family like trees brought together by nature. It is natural, and it’s the way we’re often given to explain what adoption looks like.

Although After Yang is ostensibly about a young girl coping with her feelings after her family’s beloved robot shuts down, again, like Columbus, Kogonada is able to explore so much more. Her father (Colin Farrell) is able to reach back into the android’s memories and recognize his own shortcomings, which also come with startling epiphanies. It might be a mundane conversation they share over tea out of a Werner Herzog documentary or the wide-eyed wonder in which this technosapien (Justin Min) interfaces with the world.

Ironically, media often considers tales where it is the technology pulling us out of our rooted place in our world and society, if not totally undermining it altogether. But perhaps it also has the capacity to bring us closer, whether it’s to our spouses or our children. After Yang is ultimately a hopeful exploration and one worth further consideration. Science fiction such as this requires a resolute belief in the beautiful necessity of human relationships. I want more of it.

Apollo 10 and ½: A Space Age Childhood

Ever since the early days, Richard Linklater has been intrigued by the capabilities of rotoscoped forms of animation. It certainly gives Apollo 10 and ½ a very distinct visual aesthetic. But what makes the film truly gratifying are the wafts of nostalgia visible throughout its frames. Backed by a Wonder Years-style voiceover from Jack Black, we’re able to fall back into the ’60s of Linklater’s childhood while being inundated with all the pop cultural touchstones and everyday realities that came with life in 1969. NASA and the upcoming moon landing seem to be on everyone’s minds even as siblings and families concern themselves with school or the new records to add to their personal collections (be it The Monkees or Herb Alpert’s Whipped Cream).

I’m a sucker for these trips down memory lane, and not just because I like to wear rose-colored glasses. It has to do more with mimesis and getting to see a fully embodied representation of a time and era I can never know firsthand because I never lived through its banalities as well as its major cultural events. In fact, the rotoscope images accentuate this aura by giving us footage, TV shows, and even record albums we’ve seen before as secondhand artifacts, and still somehow through this animated mediation, they are rejuvenated before our eyes.

Linklater has always been noted for his interest in the mundane, in conversation, and in the depiction of passages in time. These are some of the joys of Apollo 10 and ½, but it’s also given to the flights of fancy that boyish imagination and space exploration seem to condone. We’ve seen many similar meditations from filmmakers even in 2022 alone. Rarely have they seemed totally self-indulgent. Somehow this is another one that feels real, honest, and intimate.

EO

There’s no way for EO to be viewed outside the cultural purview of Robert Bresson’s 1966 Au Hasard Balthazar, another tale about a donkey who bears the burdens of life. It occurs to me there are two kinds of people who undertake such a project. You’re either so full of the brash vainglory of youth, you have no fear or deference to your forefathers. The other option is you’re so along in years, you need not worry about what others think. You go ahead and make the movie anyway because Balthazar was a poignant film well worth paying homage to.

At 82, Czech director Jerzy Skolimowski fits firmly into the latter category, and I’m so thankful we have this film from him. The longer it goes, the more entrancing it becomes with the four-legged EO as our ready conduit of both the anthropological world around him and also the tranquil, sometimes utter bleakness of nature. The comic inflections of social structures, soccer pitches, and what have you, feel adjacent to some of the great comedies of some of his Czech New Wave brethren. I’m thinking of Fireman’s Ball or even Closely Watched Trains, and yet this is a film made decades later.

He does feel like the last of a catalytic generation and while there is some melancholy that comes with this, it’s also a stirring testament to the labyrinthian journeying that comes with filmmaking. Somehow this donkey represents the road traveled quite well, and it’s far from a Balthazar redux. Skolimowski has enough experience and humanity to make EO stand on his own feet in deeply moving ways.

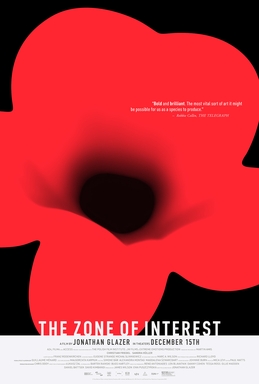

Zone of Interest opens with a blank screen and a collage of sound; it’s almost like it’s priming us for the movie ahead. Because it’s not a conventional movie by any stretch of the imagination. It’s difficult to put arbitrary labels like good and bad on it since it’s so different than what we normally get in the cineplexes.

Zone of Interest opens with a blank screen and a collage of sound; it’s almost like it’s priming us for the movie ahead. Because it’s not a conventional movie by any stretch of the imagination. It’s difficult to put arbitrary labels like good and bad on it since it’s so different than what we normally get in the cineplexes.