Religion doesn’t always play a prominent role in the films of Alfred Hitchock — he could possibly be considered a lapsed Catholic — but I Confess is his most overt exploration of moral and religious convictions. Although one could make the argument that he’s most interested in the mechanisms created by the moral conundrum since his priest becomes another innocent man accused. Nonetheless, the story speaks for itself.

It opens in quintessential Hitchock fashion as signage seems to indicate a route and then moments later a murder is announced with a body sprawled out on the floor. A man walks down the street briskly in the cosset of a priest. If nothing else, it suggests a man of the cloth might soon be implicated.

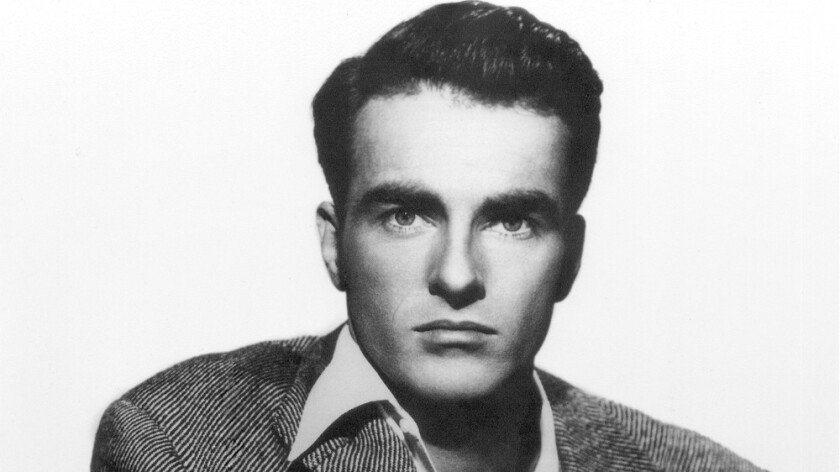

Father Michael Logan (Montgomery Clift), who will soon become of primary importance, is in the church when he is met by Otto Keller (O.E. Hasse), who works in the local parish with his wife. The Father has always been good to him, his friend even, and now he has a confession.

The confessional becomes such a powerful dramatic element: It’s been used to stirring effect in everything from Leon Morin, Priest to the more recent Calvary. In I Confess it conveniently sets up Hitchcock’s core dilemma. The flustered European immigrant confesses to the murder of a man named Vilette. Priests, of course, take a vow of confidentiality. Thus, the picture is not entirely a mystery. This is laid in the audience’s lap before we know what exactly to do with it.

Everything must become far more complicated. It involves the Father’s past relationship with the now married Ruth Grandfort (Anne Baxter). That was many years ago, although Logan remains above reproach.

Still, the police inspector (Karl Malden) needles him and cannot understand why he will not be more compliant. After all, he was supposed to meet Vilette the morning after his death, and he was seen with the young woman on the street corner, the day after. It’s true enough, but he will not divulge more regardless of how it looks.

Flashbacks clog up the story’s midriff even as it becomes imperative to inform the narrative. Because before he ever took his vows, they were in love. He went off to war and she was left despondent, receiving small comfort from her employer and future husband: Pierre.

Not all the performances feel altogether pristine or polished but as with the environment, this is a bit of added authentic charm. The more readily-remembered Hollywood actors feel mostly like dressing compared to Father Logan — Malden’s obdurateness might be the exception. Still, this is not altogether problematic and while the picture’s not exactly taut, it does feel psychologically distressing. Clift is made to suffer in silence.

We often forget, with the lustrous Technicolor glories of the Paramount years and pictures from Rear Window to Marnie, that Hitchcock was comfortable with smaller scale and black & white. Quebec is a very unique locale, but it effectively serves his plot and the evocation of provincial character quite well.

Although Hitchcock was never one to see eye to eye with so-called “Method actors,” I think of Clift and Paul Newman in particular, there’s no argument that he allows Monty to shine even sets him up for a nuanced but ultimately towering performance. There’s a quiet magnitude imbued by his stoicism in front of the camera.

He literally becomes a Christ figure and it’s no mere coincidence that Hitchcock shoots looking down past a sculpture of a man carrying the cross as Logan himself walks below on the street. Or for that matter, how often do you see a crucifix so prominently featured in a courtroom? It’s because this courtroom drama has a priest on the stand. The whole movie is playing out through what he will and will not do. His convictions dictate what will happen.

It’s the district attorney (Brian Aherne) who has the undesirable job of getting a conviction by doing his job to the best of his abilities. This means cross-examining a mutual friend (Baxter) as well as the man of the cloth. Is he in a sense, Pontius Pilate? Because even if Father Logan comes out of the trial alive, the media attention and the aspersions on his character can never be undone. He will be faced with public ignominy.

He’s also made to walk the gauntlet so many times; Hitchcock blesses Clift with some phenomenal close-ups and allows the camera to take on his protagonist’s point of view multiple times. He’s not the only one, but one can hardly forget the very final scene in the Chateau Frontenac Hotel: The Father goes in to confront the man who was going to let him take the rap for a murder he did not commit.

The man has a gun. He’s holding himself up and by now he’s desperate already, having killed at least one other person. The room couldn’t seem larger and still, with a kind of peerless conviction, Clift’s hero makes the long walk prepared to sacrifice himself yet again.

Ultimately, he is vindicated; there is a sense of justice, but what a terrifying portrait it is. For those without major religious convictions, it might feel absurd. I must admit it seems almost inconceivable a priest cannot alert the police about a murderer. Surely, even the Bible talks about there being a season for everything, and a time for every purpose under Heaven. Still, Hitchcock even made a point in an interview:

“We Catholics know that a priest cannot disclose the secret of the confessional, but the Protestants, the atheists, and the agnostics all say, ‘Ridiculous! No man would remain silent and sacrifice his life for such a thing.”

It should be noted, in a Hitchcock film, it usually seems like a time to kill and a time for hate because what better way to explore our moral makeup and the forums of human justice? In the end, Father Logan holds fast and is exculpated. If not only by earthly powers, then higher powers too. I’m still left to wonder what Hitchcock would have said in the confessional if he was faced with it.

You can tell a lot about a man from his fears as well as his vices. What stands out about the picture is how it never feels undermined by jokes. It feels as sincere as the man at its core. For some, it might be a turnoff. For others, it will make you appreciate the director even more. He willingly enters into the realm of the pious, albeit through the lens of murder.

3.5/5 Stars

Any knowledge of director Fred Zinnemann only aids in informing The Search. Formerly living in a Jewish family in Austria, he would immigrate to the bright lights of Hollywood in the 1930s only to have both his parents killed in the Holocaust. So if you think he had no stake in this picture you would be gravely mistaken.

Any knowledge of director Fred Zinnemann only aids in informing The Search. Formerly living in a Jewish family in Austria, he would immigrate to the bright lights of Hollywood in the 1930s only to have both his parents killed in the Holocaust. So if you think he had no stake in this picture you would be gravely mistaken.