Jack Nicholson was awarded the distribution rights of The Passenger soon after the movie came out, and he purportedly kept it out of circulation until the 2000s. From my understanding, it wasn’t for the typical reasons. He wasn’t trying to kill it so no one would catch wind of what a debacle it was. On the contrary, in some way, he was looking to preserve its artistic integrity and keep it pristine. What better way to do this by only allowing it to exist in your memories.

These circumstances allow for an intriguing dialogue on art vs. commerce and what this means in the Hollywood landscape. Take, for instance, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, released in the same year — wildly popular, an Oscar cash cow, and still well-regarded to this day.

I don’t want to make any unfair insinuations about Milos Forman’s film — it can still be art — but by sheer box office appeal, it readily fits the category of commerce. It was a highly successful film in many regards and no doubt a lot of people have seen it and enjoyed it immensely.

Whereas The Passenger is a film, also released in 1975, that probably only cinephiles have a passing interest in because it hardly has any visibility. Even as I dipped my toes into the filmography of Michelangelo Antonioni, I was made aware of all his other works from L’Avventura to Blow-up before I ever had an inkling of this movie.

But it does exist and it’s such a fascinating, understated counterpoint to the rest of Jack Nicholson’s career. You get a sense of why it would remain so near and dear to his heart even as it becomes difficult to categorize. For one thing, he plays journalist David Locke at his most sincere — normally he feels a bit disingenuous, here every action rings with a core resonance.

This in itself might be a strange remark. We meet Locke in Africa. He is following a fast-evolving story about the local liberation front. He’s conducted many interviews and promoted the revolutionaries, but there is this sense he still doesn’t know what he’s in the middle of. In earlier decades he would have been the imperialist trying to make sense of the natives. A generation after that he would have been Jake in Chinatown.

But the most curious development is this: Locke finds another foreigner dead in the adjoining hotel room. They shared a conversation earlier. Now, he looks to take on the man’s identity. It remains to be seen why he does it. Locke’s not a criminal or a spy; he’s a journalist, and yet there’s a premonition that seeing this other fellow’s life — a globetrotter, as it were — proves highly attractive. He’s not weighed down by the same regimen and responsibilities.

If you’re unfamiliar with Antonioni, the premise might sound like a precursor to Bourne or maybe an Alan Pakula paranoia thriller. However, it has none of those hallmarks. It’s never preoccupied with the narrative beats. They only seem to be there — to exist as a conduit with which to explore something else.

The movie shifts to Germany but location is far too convenient a reference point. The movie freely shifts wherever it pleases, within time frames, as a kind of exercise in fluid, stream-of-consciousness storytelling. Where the present and the past can literally crossover and play out into one another within a single scene. Prior conversations echo in Locke’s ears even as he begins globetrotting around the world.

Over time they play more like moments and memories than traditional scenes adding up to what we would consider a conventional plot. He meets with some revolutionaries and realizes he’s a gunrunner. His wife and her lover learn of his death, go digging through his interviews, and go looking for this missing person. However, it all spins together another totally elusive tale as envisioned by Antonioni. This is his whole modus operandi as a filmmaker.

Locke (or Robertson) thinks he’s being followed and he is, but there’s never a true sense of fear or dread. In fact, we don’t quite know what to feel. It could be called a mood piece or a tone poem although I’m not sure those are quite right.

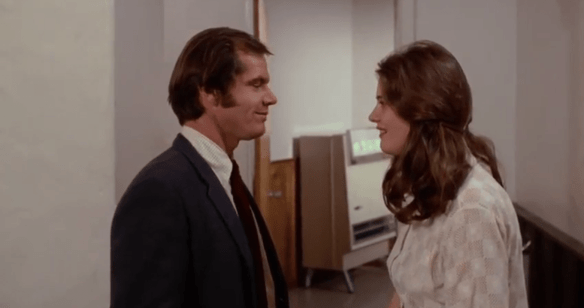

These moments are plucked out of time. There’s a chance encounter in Barcelona. He casually explains to a young French student (Maria Schneider) he’s running away. She wishes him well — hopes he makes it — noting people disappear every day. Sometimes it’s just around the corner, sometimes it’s with the cut of a film, and sometimes it’s for good. In perfect cadence with Nicholson’s amiability, Maria Schneider has a pleasant forthrightness about her; she’s another creature drifting on by, made solely to exist in this world.

It’s very rare to pull Antonioni away from the architectural landscapes he finds at his disposal because this is where he derives geometry, shapes, and with it an overarching composition for his works. Barcelona is a perfect marriage because one of its supreme talents was the incomparable Antoni Gaudi. Even a couple years of remedial art history tell us his buildings were of an unmistakable, singular design. The most startling progression is from dour Gothic interiors to these near-fantastical exteriors. Like Picasso and others like him, somehow in these shapes, or lack thereof, they derive meaning. Because how else are we going to ascribe it to our world?

It’s fitting that a movie that’s plot was incited in a hotel room should end in one as well. There’s a near-imperceptible zoom during the film’s famed denouement — peering out into the world. Up until this point, the story seldom feels chaotic as if our hero is resigned to his fate, and he has a kind of solace in it.

Luciano Tovoli’s camera magically pushes through the bars of the window to view the sandy plaza outside. It’s these tracking shots across the horizontal plane of existence I won’t soon forget opening up the world to be fuller and more immersive. In one full cycle of the camera, it’s like we see the plot and a life’s journey come to its conclusion all in one fell swoop.

Like others, I spent time deliberating over the meaning of the title. In Italy, it was known as Professione: Reporter. In English, it was changed to The Passenger. There might be numerous logical readings for both, but for me, I couldn’t get the picture of those two dead bodies lying on beds. You have to see them to know what I mean. They feel empty when they are found. Only a shell of a human being because it’s true the spirit or the life force of the person or whatever you to call it, is gone.

We are a culture rich in euphemism or closer yet metaphors. In the biblical text, Jesus gave up his spirit. Others have fallen asleep. Hamlet talks about shuffling off this mortal coil. And others have passed on. For me, this is what the title resonates with. This idea of how we are only on this earth a finite time. We are not solely defined by our body and our vocation and all these other intangibles.

It’s the spirit inside — the beating heart, the breath in our lungs, our souls — these are what make us alive as human beings. So quickly do we arrive and in another moment we are gone. In The Passenger, death is not violent. It’s only a voyage finally coming to an end.

What makes it disconcerting is the lingering alienation and dissatisfaction propagated by the world. It feels like a sullen place to be. Death as such seems like a tranquil respite. Each must decide for themselves if this holds true for them. Because surely we are not meant to live life without hope, existing in a constant state of listlessness. There has to be more.

4/5 Stars

Anyone who takes the time to search out this movie whether the reason is a young Jack Nicholson who wrote, helped finance, and starred in this western or because it’s directed by cult favorite Monte Hellman, they probably already know it was shot consecutively with The Shooting. Whereas the first western has an unnerving existential tilt as the plot takes us through an endless journey across the oppressive desert plains, you could make the claim that Ride in the Whirlwind is a more conventional western.

Anyone who takes the time to search out this movie whether the reason is a young Jack Nicholson who wrote, helped finance, and starred in this western or because it’s directed by cult favorite Monte Hellman, they probably already know it was shot consecutively with The Shooting. Whereas the first western has an unnerving existential tilt as the plot takes us through an endless journey across the oppressive desert plains, you could make the claim that Ride in the Whirlwind is a more conventional western. Crime films, westerns, and horror. It’s easy to see why these genres make arguably the best B-pictures, all things considered. It lies in their ability to deliver thrills with minimal capital and a bit of inspiration. Film Noir is by far my favorite but a film such as The Shooting makes me love shoestring westerns too. Except that’s just an initial gut reaction. What happens over the course of this film truly plays with our preconceptions. Its ambitions being rather curious.

Crime films, westerns, and horror. It’s easy to see why these genres make arguably the best B-pictures, all things considered. It lies in their ability to deliver thrills with minimal capital and a bit of inspiration. Film Noir is by far my favorite but a film such as The Shooting makes me love shoestring westerns too. Except that’s just an initial gut reaction. What happens over the course of this film truly plays with our preconceptions. Its ambitions being rather curious. Upon watching A Few Good Men for the first time, it was hard not to draw parallels with An Officer and a Gentlemen for some reason and it went beyond some cursory elements such as both films involving branches of the military. Perhaps more so than that is the intensity that manages to surge through the plot despite the potentially stagnant battleground like Cadet Schools, Courtrooms, and the like. And that can in both cases is a testament to the stellar performances in front of the camera.

Upon watching A Few Good Men for the first time, it was hard not to draw parallels with An Officer and a Gentlemen for some reason and it went beyond some cursory elements such as both films involving branches of the military. Perhaps more so than that is the intensity that manages to surge through the plot despite the potentially stagnant battleground like Cadet Schools, Courtrooms, and the like. And that can in both cases is a testament to the stellar performances in front of the camera.

“If you had a choice would you either love a girl or have her love you?”

“If you had a choice would you either love a girl or have her love you?”