The film’s title couldn’t be more true as Irene Dunne and Charles Boyer pooled their talents for a third go-around, and what a pleasant experience it is. If it wasn’t evidenced by the soaring romance and light comedy of Love Affair and When Tomorrow Comes, they share that thing that is so often conveniently distilled into the word “chemistry.” You can’t bottle it, and it’s rarely a given. Still, on the screen together, something tangible happens.

In this regard, the plot almost feels of secondary importance though Together Again begins with a quirky and, frankly, intriguing premise. One of the most prominent landmarks in the town of Brookhaven, is a giant statue to the late Mayor Crandall.

After his sudden departure from this mortal coil, his wife Anne (Dunne) was quick to shoulder the responsibility. Now she lives in their home with her curmudgeonly father-in-law (Charles Coburn) and a histrionic daughter (Mona Freeman), who is beside herself with hysteria. You see, the head of her beloved father is knocked clean off his body by a stray lightning bolt.

Being the faithful civil servant that she is, the mayor sets aside her day-to-day duties post haste in order to enlist the services of a sculptor. She takes a day trip to the city in order to requisition the new statue, but the artist she calls upon is hardly who she was expecting. Then again, George Corday (Boyer) was hardly expecting to meet such a beautiful mayor. Every mayor he’s ever known was a stodgy old man. They’re both taken aback.

Despite her misgivings, she manages to get talked into going to a quiet little club only to renege their partnership. He’s not the kind of innocuous creative type she had in mind to do justice to their sleepy little town. Obviously, Boyer smolders too much with latent passion and charisma. He unnerves her.

Could the movie be over? She wanders off to the powder room. She looks curiously like the showgirl providing the floorshow. Then, the attendant offers to iron her dress with a wet spot. Minutes later, a raid and someone running off with her garment, means she’s caught in a compromising position when the police waltz in. If we see it coming from a mile away, the beauty of the character is how she walks into it all so innocently.

Anne flees her hotel before Corday can catch her, and she tries to ignore her obscured face on the scandal sheets. It’s all a horrible misunderstanding that she tries to dismiss. When she returns home, a new extravagant hat in tow (she can’t seem to misplace it), she’s practically jumping out of her shoes.

The evolution of Dunne in the picture might be familiar to those who’ve witnessed her about-face in Theodora Goes Wild. There’s this sense of propriety that all a sudden is besieged with all the fits and giggles, quirks, and foibles one comes to expect in a screwy brand of comedy. As her daughter observes, she’s become a little “leapy.”

As mayor, she’s supposed to “keep her shirt on,” but she’s concerned what happened on her little excursion will come out and, of course, it does. This time it’s not Melvyn Douglas but Charles Boyer catching her in her “lie” so to speak. She’s traded out a salacious novel-writing career for a wild night of accidental indiscretion that might rattle her upright standing as mayor of her small town. Her beau even winds up sleeping on the premises much in the same manner of Douglas before him.

It doesn’t offer too much in the realm of invention, but the ongoing rapport of Dunne and Boyer keeps things convivial enough as they get caught up in your typical entanglements. Upon meeting him for the first time, Diana swoons and young love sweeps over her as she tries to dress the part and act more cultured, spending extra time plonking away at the piano. Why she even addresses him in French, when heading off to school, dropping a refined “Bonsoir” bright and early in the morning.

As her daughter tries to impress upon this gentleman her newfound womanhood, Anne unwittingly shows off a bit of her youth, with a becoming new hairstyle and a less fastidious demeanor. As Diana’s main beau, the lanky Gilbert “Good Night” Parker (Jerome Courtland), finds himself more and more scorned; his spirits are lifted by a show of kindness from Mrs. Crandall. He simultaneously alights on his own amorous advances.

There’s nothing particularly inspired in these beats. It’s Dunne and Boyer who continue to make it amicable. Under the circumstances, it’s difficult to consider any two people we would rather see together in the scenario. Coburn for one is tickled pink to finally see his daughter-in-law going in with another eligible man.

The denouement of the movie does provide some mixed signals. Granted, they feel like the status quo dichotomy in 1944. It seems Anne must make a choice between love and duty — her job as mayor or a life away from the stifling town — they are presented as mutually exclusive.

Boyer plays a bit of the cad in the final act when it seems almost laughable that she might have to choose. He draws a comparison between himself and that hat she tried to hide away on the top shelf of her closet. It doesn’t seem quite fair. There’s not much to spoil, but I won’t divulge what happens next.

Instead, my mind drifts once more to Charles Coburn; he was made for these types of supporting roles: crotchety yet secretly good-natured matchmakers. Surely he could deliver on them in his sleep.

Although it’s not quite as stellar as Theodora in the comedy department, Dunne still shows her usual aplomb, and out of personal preference, I fancy Charles Boyer over Melvyn Douglas on most occasions. This one is little different. Forgive my impudence. It’s just so good to have Boyer and Dunne together again.

3.5/5 Stars

“There’s not one woman in a million who has ever found happiness in the back streets of any man’s life.”

“There’s not one woman in a million who has ever found happiness in the back streets of any man’s life.”

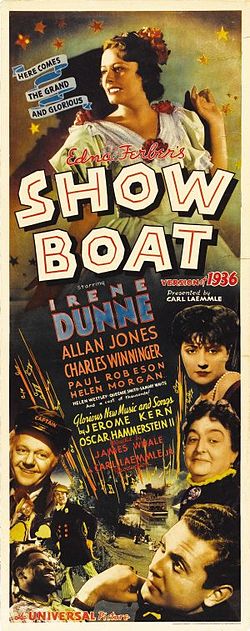

Most of what I know about riverboats can be gleaned from Mark Twain, Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, and that ever beloved Snoopy incarnation The World Famous River Boat Gambler. The 1936 musical Show Boat falls into that very same rich tradition but some clarification is in order.

Most of what I know about riverboats can be gleaned from Mark Twain, Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, and that ever beloved Snoopy incarnation The World Famous River Boat Gambler. The 1936 musical Show Boat falls into that very same rich tradition but some clarification is in order.