In Cowboy, Delmer Daves and Glenn Ford continue their fruitful partnership by examining the life of a different sort of cattleman. The movie opens on a grand mid-century establishment soon to be frequented by a cowboy named Reece. Everything is colorful and ornate in the Spanish style with gaudy curtains and wood interiors.

Thus, it begins as a hotel drama that switches out a sulking Garbo and destructive John Barrymore for a gang of cowhands and a hotel clerk’s romance. The movie would not be the same without Jack Lemmon. He is Frank Harris, a lowly clerk with the unenviable task of moving some guests to make way for Mr. Reece. It runs deeper still. He’s fallen in love with the gorgeous daughter (Ann Kashfi) though her father dismisses the young man’s affirmations of love.

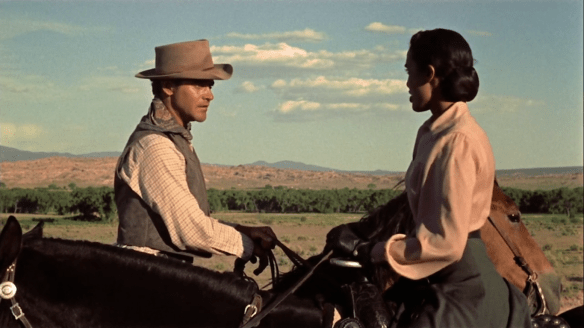

Soon enough, they will return to their native Mexico, and Maria will be a distant memory to the impressionable boy. Before he can sort out his feelings, Reece’s contingent comes pouring in and takes over the hotel.

The whole movie is built out of these two men coming together and what a glorious juxtaposition of characters it is. The dreamy-eyed idiot and a veteran cowboy, pragmatic and hard-bitten. Ford and Lemmon have been created on their most fundamental level to chafe with one another. Still, the tinge of comedy is not entirely imperceptible in the setup.

In their introduction, you have Lemmon sidling up to Reece’s bath to get in with his gang while Ford shoots stray cockroaches with some relish. Equally important is how real life intersects with film fiction because Glenn Ford built a storied career in westerns, even if you only count his films with Delmer Daves. Lemmon was always the common, everyman schmuck. Now he’s a tenderfoot barely prepared to place his backside on a horse.

Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo explores a modern mode of western calling for a different brand of star. Lemmon could easily be built into the City Slicker archetype, lovelorn and ready to prove himself. The first time Harris gets tossed from his horse it feels like a kind of initiation. He’s begrudgingly allowed to ride along, but there’s not going to be any concessions for him. He better toughen up or get out.

As their journey together begins, Daves does remind us about the austere beauty out on the range. It’s a tough life certainly, there is no Sabbath; you must learn to sleep in the saddle and pick yourself up when you fall. And yet there’s a newfound appreciation watching the cowboys at work against nature’s grandeur all around them. It feels like a noble profession out on the land using your heads and working hard each and every day.

Brian Donlevy was a minor icon of the 1940s, once he overcame his relegation as a tough guy, but almost 20 years later, there’s a modicum amount of joy seeing him still up to the task at hand along with such disparate figures as Dick York and Richard Jaeckel, each prone to their own sins, whether drink or violence.

It becomes apparent as a long-form almost classical tale, Cowboy can easily be compared with other cattle movies a la Red River. Because while we have Jack Lemmon and Ford’s not totally averse to humor, there must be hardship and conflict stirred up. They take up the mantles of John Wayne and Montgomery Clift, vying for control as they exorcise personal demons and hone in on their priorities.

Later there’s a strangely poignant funeral sequence after one of the trailhands (Strother Martin) is killed in a rattlesnake attack instigated by a practical joke. These unfortunate circumstances lend a troubling undercurrent to the sober congregation. It’s Frank’s first lesson in the cruelty of the trail.

In another moment, one of their group is drinking it up at a Mexican Cantina and is obviously about to be jumped by some jealous locals. Harris is intent to help him, but they live by the credo: if a man’s old enough to get himself into trouble, then a man’s old enough to get himself out of trouble. There’s no sentimentality or loyalty as far as they are concerned. You do your work and look out for your own hide.

These events are not completely isolated, but they put the newest trailhand over the edge. We know he’s naive about what it takes to survive out on the road, but he also highlights the callous code these men are willing to live by. He barks at Reece, “I thought I would be living with men, not a pack of animals.” It changes him thereafter. He won’t allow it to affect him anymore.

Cowboy hints at Jack Lemmon’s substantial chops as an actor. And I use the term in the sense it is often used. Sometimes comedy is not considered true “acting” to the same degree as drama, but it seems comedic actors are capable of some of the best drama. Perhaps they can see one in the other or vice versa.

Because the movie begins as a kind of comedy on the range. At least this is what it hints at and what we know Lemmon can offer. And then it builds into a story with greater ferocity and also emotional depth. It’s not just about a jilted romance, but a disillusionment in this admiration he had for a certain brand of masculinity. There’s something inwardly thrilling in this transformation even as we see the change projected over Lemmon’s character.

With grit and determination, Harris gets below the border to see his girl once more, but he’s been made callous and her circumstances are different. It feels like a betrayal. In these specific scenes, Dalton Trumbo, who was currently an exile in Mexico due to the Blacklist, calls upon a locale not far removed from him or even his earlier bullfighting effort, The Brave One. Also, he would go into a further deconstruction of the cowboy archetype in Lonely Are The Brave only a few years later. It’s difficult not to view these films across the same continuum.

True, it is a tale about cowboys — their lifestyle, whether real or imagined — and both the toxicity and mythos that comes with such a life. I couldn’t help thinking, like The Magnificent Seven, it fashions itself into something greater — a broader exploration of morality. Masculinity in the West takes on many facets be it survival, gunplay, or getting the girl, but it’s movies like these making it about a kind of stalwart integrity.

Like The Magnificent Seven, it starts out as a mission — representing a job with specific utility — and becomes a parable of doing right by your fellow man. Lemmon must mature and Ford must soften until they both settle on a newfound prerogative. The movie reverts back to the cycles these men know best, and yet not without changing them.

Cowboy is easily the most unheralded picture in Delmer Daves’s western trilogy with Glenn Ford, but it’s held together by some more stunning imagery and two truly complementary performances. Now as they lounge side by side in their bathwater picking off cockroaches, there’s a mutual respect between them along with a newfound parity.

3.5/5 Stars