As the saying goes, the bigger they are, the harder they fall and Toro is a big man. He’s a sculptable Argentinian bumpkin who will quickly be fashioned into a killer in the boxing ring. Rod Steiger plays Nick Benko, a shifty promoter looking to groom his latest talent and set him up for success. It has nothing to do with actual training.

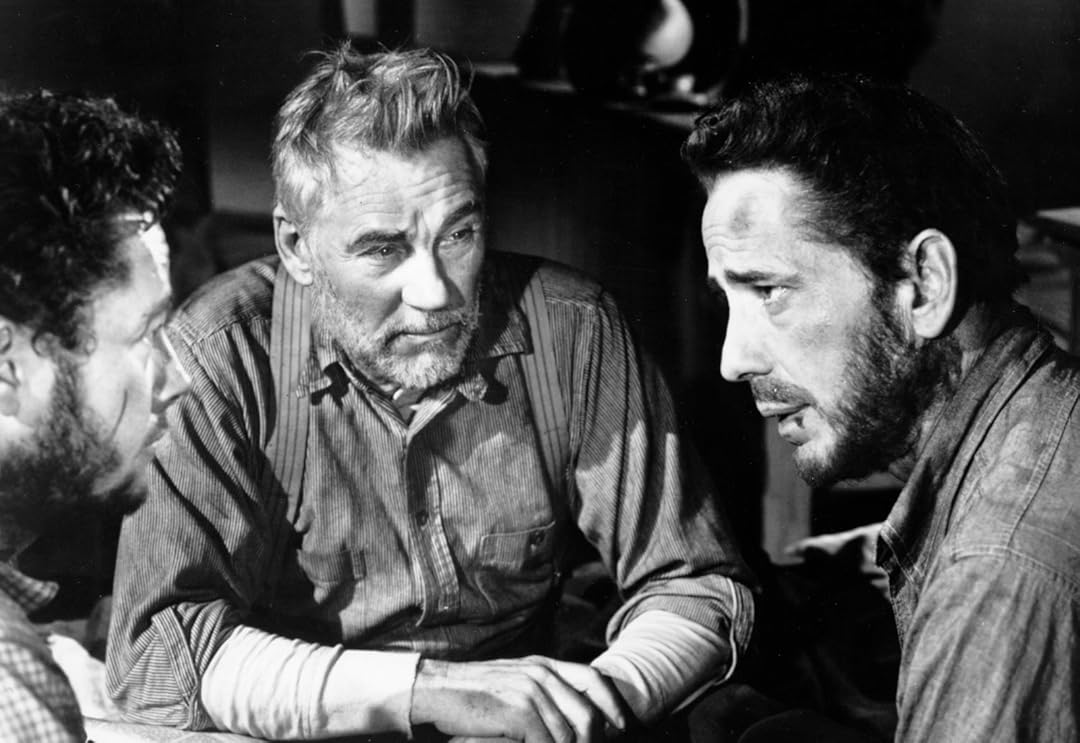

First, he calls in a veteran sportswriter to stir up some good publicity. Things have changed. No one wants to fight anymore when they could go to college. It’s more like playacting than an actual sport. You’ve got to give the audience a show and that means publicity (and staging the results). Eddie Willis (Humphrey Bogart) has long been concerned with holding onto his self-respect in the journalistic profession. Now he’s finally caved to Benko’s racket because he wants to get ahead for once in his life. His coffers aren’t as full as they could be.

It becomes increasingly apparent, in spite of all of Nick’s high words and cajoling, he’s obviously no good. Eddie knows what it all means as he watches a dirty fight and the ensuing repercussions of each subsequent business agreement. Nick’s operation is taken care of by an army of hoodlums. All these faces pop up here and there, making appearances and showing up ringside or in hotel rooms. Bogart joins the king of the creeps by pocketing 10% for himself if he can keep them out of jams.

While Bogart carries the picture, I couldn’t help thinking about some of the intriguing sparring partners he has — not the big names but the likes of Harold Stone and Edward Andrews. Because the movie feels like an analysis of the entire ecosystem and why people do the things they do. An added tinge of realism is given by real-life fighters like Jersey Joe Walcott and Max Baer.

Jan Sterling appears in a role reversal playing the principled wife watching her husband slowly slip away from her as he’s swallowed up by his all-consuming job. At first, I was intrigued until she slowly evaporates in a part that does not avail her the opportunity to do anything substantial.

It’s necessary to take a brief moment to mention screenwriter Budd Schulberg too. Like A Face in the Crowd, it’s a story documenting the perils of television and media in general. Toro is no Lonesome Rhodes; he’s a bit of a stooge, but the men behind him are able to orchestrate everything to easily manipulate a response out of their target audience, and it’s all for monetary gain.

I’ve always heard mention of the collaboration between Schulberg and Spike Lee focusing on the bouts between Joe Louis and Max Schmelling. Although the younger director vowed to get the production made after his friend’s passing, it’s still reassuring to know Schulberg already had a portrait of the boxing world put to the screen. Not surprisingly, The Harder They Fall is unsentimental, and yet it still manages to humanize many of the fighters as victims of a system.

What strikes me about the film is what it decides to spotlight and what it leaves to our imaginations. We know the reason for all these back parlor deals — it’s to prop up the gambling — but the movie rarely pays this much heed. It’s simply understood. And also the movie focuses on the families and the business outside the ring. It’s as if everything between the ropes is already a foregone conclusion, and it is, so we hardly need to focus there.

Instead, it’s the drama beforehand: Chief (Abel Fernandez) won’t take a dive because his family is in the audience. Then, there’s Dundee (Pat Comiskey) an old journeyman dealing with head trauma from his last fight. He’s barely ready to face off against the new challenger, and it doesn’t bode well. Still, each fight paves the way for Toro’s chance at the champion (Max Baer) and some real promising money. This is what Nick has been striving for from the beginning.

There’s an abrasive whininess to Steiger’s whole performance that keeps everyone on edge. I can understand any complaints of the actor being too intense, but he’s also one of the primary attractions because his unscrupulous fixer personifies everything crooked about the racket. It’s always gangsters or businessmen in suits with all the power, but Steiger effectively makes these skeevy mugs into slimy parasites. He feels like a new, different brand of antagonist, and frankly, he makes Bogey and the audience sick. The movie wouldn’t work without him.

It comes off as one of the most bloodthirsty and unsentimental boxing pictures of the era because they let this boy get absolutely butchered in the ring — building him up — only for him to get annihilated. And it’s all for money.

By the end, it’s almost ludicrous. Like A Face in the Crowd or even Network. Toro gets his brains beat out; he’s fully commoditized and then sold like chattel, and he comes out on the other side with nothing and no one to look after his interests. He’s been cast to the pavement as disposable goods.

Eddie holds the only grain of decency left and with his moral character eroding, he must make the decision to finally stand up for something greater. It’s a nervy performance from Bogart because it never resorts to bravado or any grand showing. He’s an older, wearier man now, and it shows.

Cancer would take his life far too soon, but by relinquishing the gangster roles, he offers up a different side of himself that we could not have expected without an earlier movie like In a Lonely Place. He really is a great one. I realized part of the reason I was reluctant to see the picture was that I didn’t want to acknowledge his career actually came to an end. Even if it was well over 70 years ago, I still miss Humphrey Bogart to this day.

4/5 Stars

The Pre-Code era of Hollywood is a legitimate marvel because in a span of only a few solitary years was a period of filmmaking bursting at the seams with vice, corruption, and licentiousness that we would never see again until the late 1960s.

The Pre-Code era of Hollywood is a legitimate marvel because in a span of only a few solitary years was a period of filmmaking bursting at the seams with vice, corruption, and licentiousness that we would never see again until the late 1960s. Not that this should deter you completely but The Enforcer isn’t a particularly unique crime film by any stretch of the imagination. Still, we have Humphrey Bogart headlining the police procedural not unlike a Call Northside 777 (1948), The Naked City (1948), or Panic in the Streets (1950).

Not that this should deter you completely but The Enforcer isn’t a particularly unique crime film by any stretch of the imagination. Still, we have Humphrey Bogart headlining the police procedural not unlike a Call Northside 777 (1948), The Naked City (1948), or Panic in the Streets (1950).