Some might recall one of the reasons given for Citizen Kane not actually being based on William Randolph Hearst is Welles’s assertion that Marion Davies was no washed-up actress being propped up by her influential husband.

In fact, it’s easy to imagine Hearst being more like a Howard Hughes, hindering careers with his meddling more than he helped them. However, up until this point, I had no way of knowing, aside from hearsay passed down through generations. Thankfully, with the medium of the movies, as long as there are artifacts left over, we’re able to draw our own conclusions.

King Vidor’s Show People is such a film for Marion Davies and now that I’ve seen it, there’s an opportunity to put the Kane myth to rest of my own accord. While I don’t know if I could quite call Davies a luminescent talent, what becomes even more evident is her sense of humor. She’s able to laugh at herself and do a send-up, but far from subjecting her to criticism, it allows her to gain more of the audience’s good graces.

Perhaps I only have a burr in my sandal — holding a rather jaundiced view of Hearst — however, it seems to me, he could not understand the movies with the good-humor of his mistress. He was afraid that she would be betrayed by comedy. It makes her look all the better over 90 years later.

The world is quickly introduced as one might expect with your prototypical portrait of Hollywood: the names emblazoned on all the billboards and everyone is looking to make it big at one of the studios. Southern gal Peggy Pepper (Marion Davies) comes out west with her father, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed. They don’t know any better, driving up to the studio gate as nice as you please, ready to get into pictures.

From the studio lot to the casting office, it’s an eye-opening experience to see the world as it was in 1928, fabricated for the movie mills of Hollywood or not. There’s a factory-like industry about it, but also the kind of bustling excitement we attribute to the movies when the industry was still in its infancy and the landscape was still wide-open enough that it feels like a Peggy Pepper can still make it.

Of course, even back then, it wasn’t a cakewalk, and she needs a way in. In the commissary, she and her father meet the madcap commoner Billy (William Haines) with a giant grin on his face and a friendly boast to help her crash the movies.

She shows up at Comet Studios where Billy’s talents are enlisted as a clown, and she gets a bit of a rude awakening if she hasn’t already been partially disillusioned by Hollywood. It’s not exactly becoming to find yourself sprayed in the face with seltzer water. Hearst probably wasn’t too keen on it, but Davies wears it well, and her audience behind the camera breaks out in belly laughs.

It’s fascinating to see Show People playing with this very concrete dialectic between the merits of drama vs comedy, which no doubt has been up for contention since the dawn of theatrical performance.

There’s often this unfair dichotomy between real art as opposed to content that makes people laugh and makes them happy. In this man’s opinion, comedy is one of the most underappreciated of the arts; it’s hard to be funny on cue. Penny and Billy sit in on a movie preview in front of Mr. and Mrs. Audience, and it’s in this environment — even frequented by their director — where they see the honest reactions of the general public. There’s nothing quite like it.

As Show People progresses, the well-worn archetypes feel like cliches because we’ve witnessed them for generations. It’s certainly familiar in one of the most persistent stories in Hollywood lore: A Star is Born. How many times have we seen it?

It’s inevitable that our two youthful talents — now deeply fond of one another — will be forced to traverse divergent paths laid out before them. Penny finds herself a highly sought-after starlet, and she doesn’t want to leave her man, but there’s no place for him. He takes it on the chin good-naturedly.

But time has certain effects. It changes Penny. Not only is she under contract at a studio known for high drama even taking on a more elegant moniker: Patricia Pepoire. More importantly, she’s become an incorrigible prima donna with an insipid sense of entitlement and self-importance. She’s not about to accept vulgarity or producers disturbing her equilibrium. All the life and vivacity Billy found in her seems to be gone. At the very least dormant.

He may still only be a clown doing stunts and she a highbrow moneymaking talent, but in the end, the audience is fickle. They are quick to turn on you. Who can you count on if not your friends? Show People‘s ending is too pat, but it’s probably a necessary conclusion. Penny skips out on a tasteless marriage for seltzer and custard pies in the face. Take your pick.

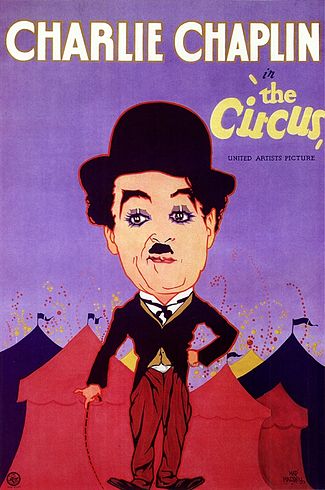

From a historical point of view, Vidor’s picture is crammed full of timely cameos — the most obvious to spot might be an autograph-seeking Charlie Chaplin (“Who Is That Little Guy?”). For that matter, silent heartthrob John Gilbert shows up multiple times on screen and in the flesh. It’s a definitive reminder that the celebrity cameo has been alive and well for a long time, particularly those involving Hollywood stars.

Because the laundry list of contemporary talents is quite long, which makes sense given Show People’s total engagement with Hollywood moviemaking and movie stars. One of its most prominent shots involves a track across a table during lunch as all sorts of personalities sit in one space. It might take some detective work for the modern viewer, but featured before us are the likes of Douglas Fairbanks, Norma Talmadge, and western star William S. Hart.

Similarly, Vidor gets an in-movie cameo playing against his leading lady — the real Marion Davies — and her alter ego catches them in action. Later, the director is shooting a war picture that might be a nod to the Big Parade, if only a fictitious rendition.

But we must return to that great monument of high comedy: Citizen Kane. Even if Hearst was convinced comedy would tank his mistress’s career, Davies shows a poise and confidence of spirit to give herself over to the laughs. The film’s dichotomy of comedy and drama plays out for us in real life. It ultimately paid heavy dividends at the box office, and Show People was one of the lingering successes of the silent cinema even as talkies were swarming the studios.

Although this was probably the pinnacle of her career, Davies also was not one of those trumped-up casualties of the revolutionized movie industry. Catch her in Going Hollywood across from a baby-faced Bing Crosby to find her talking (and alive and well). The same might not be said of William Randolph Hearst.

3.5/5 Stars

Note: The cut I viewed included a synchronized soundtrack similar to Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans.

Well, here’s another fine mess you’ve gotten me into.

Well, here’s another fine mess you’ve gotten me into.  “A picture with a smile — and perhaps, a tear…”

“A picture with a smile — and perhaps, a tear…” Prior to the making and release of Monsieur Verdoux Charlie Chaplin had undoubtedly hit the most turbulent patch in his historic career and not even he could come out of scandal and political upheaval unscathed. To put it lightly his stock in the United States plummeted.

Prior to the making and release of Monsieur Verdoux Charlie Chaplin had undoubtedly hit the most turbulent patch in his historic career and not even he could come out of scandal and political upheaval unscathed. To put it lightly his stock in the United States plummeted. The glamour of limelight, from which age must pass as youth centers

The glamour of limelight, from which age must pass as youth centers  But now no one’s there. The seats are empty, the aisles quiet, and he sits with a dazed look in his flat the only recourse but to go back to bed. It’s as if the poster on the wall reading Calvero – Tramp Comedian is paying a bit of homage to his own legend but also the very reality of his waning, or at the very least, scandalized stardom. It adds insult to injury.

But now no one’s there. The seats are empty, the aisles quiet, and he sits with a dazed look in his flat the only recourse but to go back to bed. It’s as if the poster on the wall reading Calvero – Tramp Comedian is paying a bit of homage to his own legend but also the very reality of his waning, or at the very least, scandalized stardom. It adds insult to injury. It’s important to know that he writes off such an assertion as nonsense and one can question whether this is Chaplin’s chance at revisionist history or more so an affirmation of his life’s actual trajectory–working through his current reality that the world questions (IE. Marrying a woman much younger than himself in Oona O’Neil who he nevertheless dearly loved).

It’s important to know that he writes off such an assertion as nonsense and one can question whether this is Chaplin’s chance at revisionist history or more so an affirmation of his life’s actual trajectory–working through his current reality that the world questions (IE. Marrying a woman much younger than himself in Oona O’Neil who he nevertheless dearly loved).