The film opens when a little black girl named Carolyn tumbles into a well buried beneath some weeds. There’s a melodramatic handling of the material, but already we see something rather uncommon with the period noir. Normally black characters live on the periphery of film noir if they exist at all.

Here Martha (Maidie Norman) and Ralph Crawford (Ernest Anderson) reach out to the local Sheriff Ben Kellogg (Richard Rober) when they learn their 5-year-old daughter has gone missing. They become the emotional center of this local drama with greater implications. As an aside, it’s a pleasure to see Ernest Anderson once again.

Those who recall him in This is Our Life (1942) will remember him to be a performer of tremendous intelligence and dignity. It’s only a shame the impediments of prejudice meant he never had a more sterling career. This film acts as a small recompense.

Upon closer inspection, The Well has shades of some other movies like Captive City or Phenix City Story where there is an adherence to faux realism as we kick around the beat meeting people, and getting to know the world they call home.

It’s fascinating to witness how this inciting incident — the disappearance of little Carolyn — sets the story in motion with Russell Rouse and Leo C. Popkin slowly turning the screw. Because it’s true there’s something rather insidious about this movie causing it to wheedle its way into our psyches.

It feels more relevant and more compelling than many of the old procedurals because of the subject of the case. It’s not just about a crime, but it’s complicated and made more tenuous with this added layer of racial tension, a very real issue even today.

Being a lifelong MASH aficionado, there’s something pleasing about Harry Morgan playing a central role as mining engineer Claude Packard. It’s quickly corroborated that he may have been the last person to see the girl; he’s a stranger from out of town, and curiously enough, he bought her a flower before sending her on her way.

It doesn’t take a genius to put all the pieces together and the racial element along with circumstantial evidence quickly brings the out-of-towner under the observation of the police.

The rumors quickly make the rounds throughout the neighborhood. In one brief vignette, a group of black students sits at a library conversing about race prejudice and a white man accused of a crime against a black child. It’s easy to forgive the blatant quality of this scene because it feels entirely unique for the era. I’ve never seen a moment like this before. But it’s not just a matter of the film feeling ahead of its time. After all, a lot can happen in 70 years, and values can change, though many things like racism feel deeply entrenched.

Still, there’s a complexity to the film that feels quite groundbreaking with something to speak to our current moment. Rather like Sam Fuller’s The Crimson Kimono, it’s a film about race, but it takes a somewhat nuanced approach.

The dramatic situation is obvious. Here there’s a white man being held for a crime against a black girl. The added wrinkle is that he didn’t actually commit a crime, but that doesn’t impact how the execution of justice is perceived by all bystanders on both sides of the racial line. It’s so easy to buy the message, “You can get away with murder if you’re the right color” because we’ve seen it play out so many countless times.

It’s also true Claude’s uncle is the highly influential businessman, Sam Packard (Barry Kelley) who runs a local construction company. He’s prepared to pay bail for his relation regardless of guilt or innocence. He doesn’t seem to care what the man did even as Claude vehemently pleads his innocence. If you’ve ever seen Kelly in another picture, he slides so easily into this role accentuated by his corpulent build and a pair of beady eyes.

From the outside looking in it’s so easy to view this as a miscarriage of justice where the authorities are steamrolled and wealth and privilege are able to get a white man out of anything. We’ve seen this before too.

At this point, retribution is all but expected, and it escalates with each successive confrontation between the divisive factions of blacks and whites. Once a tipping point is reached it’s like a never-ending feedback loop descending into chaos and quickly stoking the fires of unrest.

It strikes me how the mob is always going after the individuals in an almost faceless fashion. And both sides do it. There’s never a familiarity. It’s always swift and unfamiliar. But this kind of violence and hatred only breeds in anonymity where others are dehumanized and not dealt with as other human beings. It makes it easier to disassociate and perpetrate acts of malice.

It’s easy to gather the rest of the film is paved with this kind of violence. A full-blown riot is set to blow up the town and overwhelm any semblance of law and order. A movie like this also shows how the borders around language were so contrived. So many words were banned from motion pictures and yet the N-word flies so easily. It always catches me off guard, especially if we’re used to the normally manicured veneer of Classic Hollywood.

There are so many moments I can’t forget, but most of them are small observations. Take for instance, once when a white officer has a black kid up against the wall; he’s battered and bleeding, and he’s one of the perpetrators.

It turns out he was brawling with five white kids who the officer didn’t find a need to bring in. He gets a look from his superior and proceeds to get reassigned to phone duty so another officer can take this battered boy to the hospital. It’s a moment like this encapsulating something damning about law enforcement and the wheels of justice.

Part of me was expecting the film to detonate. With everything we witness, it’s all but inevitable. I’m hesitant to admit it, but I almost wanted it to. Instead, we get something else that’s closer to what we need. It feels like a near-timeless denouement because I need it as much today as audiences did back in 1951.

It shows people trying to help each other and trying to patch things up and figure things out. This is the hard work of reconciliation that’s not glamorous or easily cobbled together in a few solitary moments. And The Well’s also not a cloying feel-good balm to make all the bleeding hearts feel their work is done. It can’t patch over all the lingering wounds and racial tension. Not even time has done that.

Still, even as I mentioned Kelley is so easily identified and cast as a villain, the film uses this to say something more. He’s no saint, but he’s also a human being.

Billy Wilder was apparently interested in bringing the story to the screen in some form. I can see the parallels between Wilder’s Ace in The Hole/Big Carnival and this movie. However, whereas Wilder’s penchant is always toward portraying opportunistic cynicism, here we see something vying for the communal good.

Because of course, someone finally stumbles across Carolyn and that well. The movie switches directions as quickly as it starts. The whole town including mean old Mr. Packard and the accused Claude rally together their resources to rescue that little girl because there’s a chance she’s still alive and that’s all they require to act on.

That little girl becomes so crucial to this story representing so much more than her individual little frame. Forgive me, but I couldn’t help thinking about how George Floyd came to represent something else entirely in June of 2020.

I won’t try to come up with comparisons. All I know is that this movie deeply affected me, and I hope and pray that we might live in a world reflected in the rescue of that little girl. Because it says so much. If that little girl is alive now, over 70 years later (either in the film’s world or ours), I would hope she might stand as a beacon of what can be done.

What would it say about our towns if we were willing to go the extra mile to save the lost, the least of these, and the people who look different than us? It would suggest each of us has innumerable worth regardless of our skin color. It’s part of what makes us unique and individual.

These are not faceless beings lost in the masses but people known and loved. And what if it was not lip service or political PR, but actually lived out in our every day because it was the right thing to do. This feels like the movie I needed right now.

4.5/5 Stars

Note: I originally wrote this review in November 2021

Of the plethora of returning G.I. films and film noirs, this one reflects their fears most overtly and for this very reason, it might be generally the most forgotten today. That and the assembly of a lower-tier cast. Most of these names have been lost to time.

Of the plethora of returning G.I. films and film noirs, this one reflects their fears most overtly and for this very reason, it might be generally the most forgotten today. That and the assembly of a lower-tier cast. Most of these names have been lost to time.

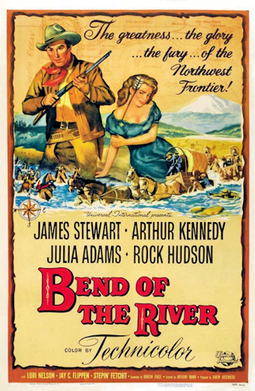

In Bend of The River, there are glimpses of the man we knew before the war. Joking and smiling with that same face. The affable charm and so on. But it’s also starkly different.

In Bend of The River, there are glimpses of the man we knew before the war. Joking and smiling with that same face. The affable charm and so on. But it’s also starkly different.

With its rather dreary title aside, The Big Clock is actually an enjoyable thriller that works like well-oiled clockwork. It’s true that oftentimes the most relatable noir heroes are not the hardboiled detectives, although they might be tougher and grittier, it’s the hapless everymen who we can more easily empathize with. Bogart, Powell, and Mitchum are great but sometimes it’s equally enjoyable to have someone who doesn’t quite fit the elusive parameters that we unwittingly draw up for film-noir. Ray Milland is a handsome actor and he was at home in both screwball comedies (Easy Living) and biting drama (The Lost Weekend). He’s not quite what you would describe as a prototypical noir hero.

With its rather dreary title aside, The Big Clock is actually an enjoyable thriller that works like well-oiled clockwork. It’s true that oftentimes the most relatable noir heroes are not the hardboiled detectives, although they might be tougher and grittier, it’s the hapless everymen who we can more easily empathize with. Bogart, Powell, and Mitchum are great but sometimes it’s equally enjoyable to have someone who doesn’t quite fit the elusive parameters that we unwittingly draw up for film-noir. Ray Milland is a handsome actor and he was at home in both screwball comedies (Easy Living) and biting drama (The Lost Weekend). He’s not quite what you would describe as a prototypical noir hero.