East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet.

East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet.

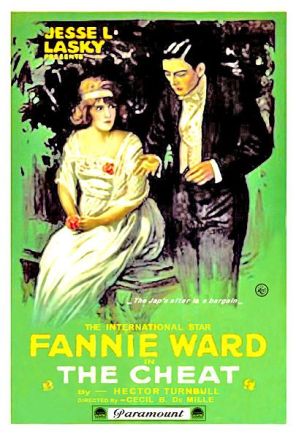

The cinema landscape was still in its utter infancy in 1915. Thus, beyond the monumental impact of D.W. Griffith, The Cheat is another subsequent landmark production for a couple of the talents it helped align.

There would be no Cecil B. DeMille without The Cheat. It was his coming-out party with the viewing public, slating him as a craftsman of delicious dramas gorging themselves on all sorts of sensual themes and pleasures. It meant bang-bang box office receipts and kept DeMille inexorably at the top of Hollywood for years to come.

Sessue Hayakawa must also receive a nod not only as a groundbreaking pioneer in an industry that still doesn’t boast too many Asian performers but also as one of the most important stars of his day. Period.

Simply comparing his style of acting with many of his peers during the silent era bears telling results. In an age, of not only discrimination and stereotypes but also extensive overacting for the camera, his parts are almost reserved in comparison. No doubt this understatement derived from the Japanese attempt to strive for the so-called absence of doing or “muga,” when it came to performances.

Because the teleplay on its own is fairly rudimentary. A well-off wife (Fannie Ward) is pouting because her husband (Jack Dean) won’t give her the funds for a new dress. He needs his investments to pay dividends first.

In being so impatient, she resolves to leverage the red cross funds she’s been entrusted with by her woman’s group — $10,000 of assets — and hands it over to an acquaintance who promises a sure thing in return. Of course, no one needs to be told it doesn’t bode well and as a result, the wife is out $10,000. She’s willing to turn anywhere, even her regular companion the suave foreigner Prince Haka Arakau (Tori in the original release).

Although gentlemanly and innocent enough at first, the lascivious prince looks to press his advantage, agreeing to give her the money — with strings attached. Extramarital drama and blackmail ensue with the tyrant putting his literal stamp on her as a sign of ownership. It’s actually quite perturbing, especially in a modern world finally looking to cast light on the sexual predation of women.

Beyond this caveat, The Cheat no doubt accentuated contemporary fears of the Yellow Peril as much as it titillated with the handsomeness of its foreign star. So while it’s playing into the long-accepted narrative including diatribes against immigration, it’s also taking advantage of the situation for pure entertainment value. There’s little discounting the purpose.

There’s a shooting that the husband admits to and a subsequent court trial full of sordid scandal-worthy confessions. The problems are ultimately amended and a happy ending found, making for an abrupt denouement meant to satisfy the masses. Given the customary, even archetypal trails the story takes, it feels much more rewarding to consider The Cheat most specifically from its place as a crucial historical time capsule outside the realm of mere plot.

Accordingly, Sessue Hayakawa was such a lucrative star during the early 20th century, it’s almost ludicrous to consider. He was making millions of dollars a year as one of the highest-paid actors of the age to rival the likes of Douglas Fairbanks or even Charlie Chaplin!

The fact that he is barely known in this day and age is a shame though it makes some sense given the cultural climate then and now. He became a screen idol in an age wrought with racial discrimination. His place as a box office smash was based mostly on his foreign allure and attractiveness as a forbidden lover. He was the toast of the town with white audiences as a fantasy character though he was rarely ever allowed to break out of the mold created for him in films like The Cheat.

We are presented with this perplexing dichotomy of this world-renowned actor who feels like an outlier in a tradition that normally emasculated Asian characters, and yet there’s still problematic perpetuations in Hayakawa’s own characterizations. It’s a two-sided issue that, regardless, is nothing short of intriguing given how early in the nascent stages of film he became a star. Dig into his history even a little bit and you are met with a continually fascinating career. For one, he entered acting on a near fluke.

After arriving in Chicago to study to become a lawyer, he was waiting for a tanker to take him back to Japan from California only to bow out and take up with a local theater. He subsequently caught the acting bug. One of the crucial figures in his early breakout was fellow countrywoman and future wife (anti-miscegenation laws forbid cross-cultural marriages), Tsuru Aoki.

Eventually, Hayakawa would emigrate back to Japan in the 1920s and slogged through WWII in occupied France of all places. After the war years, he experienced a resurgence and came to be known to a new generation of audiences for the likes of Tokyo Joe, Bridge on The River Kwai, and Hell to Eternity. For this body of work, he deserves an audience, even today, because there’s no discounting the crucial part he played, not simply in Asian representation, but in the very fabric of Hollywood history itself.

3.5/5 Stars

His ambitious follow-up to The Birth of the Nation a year before, D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance boasts four narrative threads meant to intertwine in a story of grand design. Transcending time, eras, and cultures, this monumental undertaking grabs hold of some of the cataclysmic markers of world history. They include the fall of Babylon, the life, ministry, and crucifixion of Christ, along with the persecution of the Huguenots in France circa the 16th century.

His ambitious follow-up to The Birth of the Nation a year before, D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance boasts four narrative threads meant to intertwine in a story of grand design. Transcending time, eras, and cultures, this monumental undertaking grabs hold of some of the cataclysmic markers of world history. They include the fall of Babylon, the life, ministry, and crucifixion of Christ, along with the persecution of the Huguenots in France circa the 16th century.