A version of this article was published in Film Inquiry.

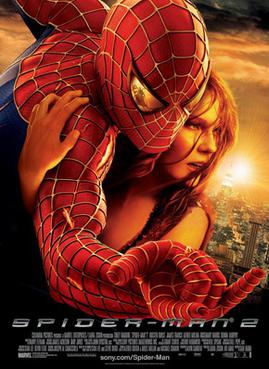

If Spider-Man was the template for what the modern superhero movie would become, its sequel feels like the standard bearer all future successors were asked to eclipse. I had never seen the movie before as I was young during its initial run, but the aura of Spider-Man was always around.

Sitting in a packed theater there was a sense of buzzing anticipation when the opening credits rolled, backed by Danny Elfman’s almost otherworldly score that hints at more eccentric inclinations. The Marvel monolith had yet to be fully consolidated and turned into a factory. For the time being, it feels like director Sam Raimi had free reign for fun.

Because we already have some context for the character carrying over from the first movie, the film’s instincts are correct in reintroducing us to Peter Parker (Tobey Maguire) with an opening gambit laced with levity.

We watch him racing to keep his job as a pizza delivery boy only to switch into the spider suit to beat mid-day traffic. There’s an extended bit with a closet full of mops that had the audience in stiches as he drops off the order sheepishly with the front desk.

I’m so oblivious but it does seem like Tobey Maguire has become a walking meme and a lasting internet celebrity based mostly on his Spider-Man persona. There’s something about his delivery that’s so awkward — maybe something about his quivering upper lip — or how he almost lisps out his lines of dialogue. But it’s also endearing.

And for every time the audience laughed, it was never out and out derision. They love this guy. He is their hero and they hold him aloft so when he goes slinging webs and rises again across the skyline, people ring out in audible cheers.

The same goes with the dialogue. Some of it might be inadvertently funny and yet so much of it is in on the joke. Raimi is wonderful in allowing for these incubated moments of a visual gag or an insert with a cameo part that has a reaction or a bit that’s good for a laugh. It can be about a stolen pizza in the opening minutes or even a terribly ordinary Peter stumbling away from a crash scene after he can’t catch his fall and proceeds to set off a car alarm.

This hints at part of the dramatic question at the center of this film. What makes Spider-Man mythology so popular is the nature of his superherodom as initially conceived by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko.

His story arc is grounded in relationships on all sides however rudimentary they might be. An aunt and uncle, his crush, and the alienation that forms between he and his best friend. What’s more, Peter is faced with the universal conundrum of what he wants versus what is sacrificial in the name of his city. With great power, comes great responsibility. But the words get muddier when it comes to specifics.

And the villainy is equally relatable. Albert Molina is sympathetic but also carries a gravitas with his physique and stage presence that wears the role of Dr. Octavius well. He becomes first a mentor and then an adversary for Peter — a perfect foil for what he represents.

His life’s work — creating a fusion power source for Oscorps — gets out of control during a public showcase. In the aftermath, his mental faculties get overridden by his new mechanical arms driven by AI. He knows not what he does and becomes a public menace who wants to rebuild his reputation, and avenge the loss of his beloved wife.

Due to the strains of his Spider-Man mantle, Peter’s grades are suffering in college and he’s absent in the lives of the people he cares about most. Aunt May is about to go through an eviction and MJ’s been making a name for herself as a theater actress and model. She feels like Peter has rebuffed her and it hurts.

Peter decides to relinquish his Spider-Man suit because he doesn’t want to keep secrets from anyone; he doesn’t want to break his promises anymore. He steps back into he shadows and lives a normal life even as the crime rate begins to rise in the city

There is the real sense that there is no longer a protective hedge against crime and other antagonistic forces. He must make a decision, and at the same time his powers begin to atrophy for inexplicable reasons.

I never thought I’d get T.S. Eliot or Joel McHale in this movie, but sure enough both are featured. Peter pulls out Eliot in a NYC laundromat as he tries to wash his Spidey suit and find new ways to woo MJ. Girls supposedly dig poetry. It feels like a small Easter egg that one of my favorite high school bands had a song featured on the U.K. soundtrack inspired by Eliot’s poem “The Hollow Men.”

Meanwhile, McHale shows up as a teller in the bank who sheepishly tells Aunt May she’s not eligible for a loan. It’s one of any number of injustices that make Peter feel powerless to help the ones he loves.

From a dramatic standpoint, the gala where he’s called upon to take pictures feels like the nadir of his story so far. An inebriated (James Franco) smacks him around in a very public setting, and then Peter learns MJ is getting married to someone else; she’s not waiting on him any longer.

These are only the personal stakes, but so many subsequent superheroes have lost this reality and gotten muddled because they dealt in expositions and nebulous things that we have little to no concern for. Here it’s simple yet effective.

The action is wonderful and the visual representation of Doc Ock with his mechanical arms has a real menace that rarely takes a false step in disrupting our suspension of disbelief. In fact, the whole film holds ups though there are a few obligatory final shots that feel like gratuitous eye candy

Aside from this, each confrontation between Peter and Octavius plays like an extraordinary piece of narrative drama that goes beyond surface level pyrotechnics. It’s meant for Saturday matinees as they duel it out inside the bank, scaling sides of buildings with Aunt May in the balance, or even battling over a railcar in a chase that evokes The French Connection while still applying a Spidey twist.

What a wonderful and mysterious thing is it for Spider-Man to lose his mask, and far from castigating him or just wanting a piece of his celebrity, the people he has just saved acknowledge his youth, and vow to keep his secret. There is a neighborliness and a desire for the communal good that feels like wind under our sails.

Because while other installments about superheroes explore characters’ isolation, anonymity, and identity as vigilantes, there is a sense that this Peter Parker does not have to worry. These people are protective of him, grateful for what he has done, and he deserves their care. He deserves grace. After all, he’s only a teenager.

What’s more he has a girl who will stick by him as he looks after the city. There is a precise moment of truth where Peter is able to allow his girl know his true, full self. It’s a supreme gift for the character.

Looking back now 20 years on, Spider-Man 2 is an early 21st century depiction about the dangers of AI, but at its core it’s about the choice. Every great hero must decide what to do in the name of self-satisfaction or personal sacrifice.

The movie would also maintain the more dubious tradition of franchises outstaying their welcome. I’ve been told Spider-Man 3 jumped the shark, and yet I imagine even now there is a nostalgic patina hanging over this trilogy.

Spider Man 2 is a wonderful delight, and it’s a pleasure to see it with an audience who care about the movie so profoundly. It means something to them even after all these years. They may be older, but they come to this movie with the same reservoir’s of affection. It’s the effulgent joy of any little kid who’s ever had dreams of being a superhero.

I’ve never been into ardent superhero fandom, but now finally getting around to Spider-Man 2 after the fact gives me a newfound appreciation for my peers. I see the hype. I’m still hoping the Marvel fad has finally begun to abate for more eclectic forms of entertainment, but that doesn’t mean we can’t celebrate where these films came from.

4/5 Stars