His Motorbike, Her Island (1986)

There’s an immediate aesthetic artifice to His Motorbike, Her Island. Our hero is cool and simultaneously cruel representing a husky-voiced, brusque masculinity that feels no doubt appealing and equally toxic. He recounts his life’s observations through voiceover — the monochrome dreams making up his memories — and as such the movie slaloms easily between black & white and color.

It feels perfectly at home in its moment as part ’80s biker movie full of style. Some of this no doubt comes from director Nobuhiko Obayashi who always seems to have a propensity for commercial pop culture imagery. I would hesitate to call him a technician, and yet since he both edited and directed many of his films, maybe I don’t want to use the label because it sounds too austere.

His films are suffused with a vibrant energy and although the comparison misses the mark, the only reference I could think of was Richard Lester. I’d be interested in hearing who others bring up.

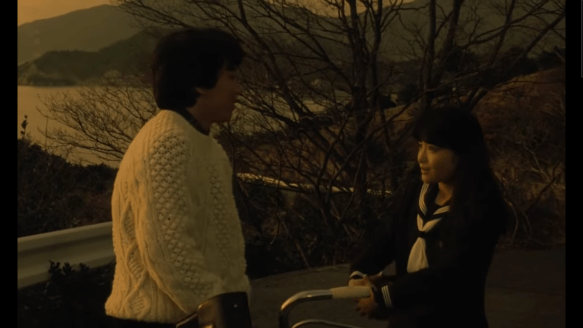

The movie’s premise is quite simple. Koh Hashimoto (Riki Takeuchi) runs errands on his motorcycle part time. His idle hours are taken up with a docile beauty name Fuyumi. He even gets in a duel with the girl’s older brother, who’s worried for her honor. Whether the outcome impacts his view of her or not, Koh, breaks it off. By his estimation, she’s boring (all she knows is crying and cooking).

Koh is looking for the Japanese version of the aloof dream girl, and he finds it in Miiyo. She captivates him with her confident vivacity, taking pictures of him, chatting in the onsen, and ultimately taking up his first love of motorcycles.

Their relationship blossoms when he visits her hometown out in the country during Obon, and we witness how the summer holiday is rooted in both a veneration and a celebration of dead loved ones. Koh’s captivated watching Miiyo dance during the festival proceedings. It’s something about her spirit he finds so attractive.

It also signals the film’s dangerous edges. Because if I wanted to distill His Motorbike, Her Island, down to its essence, we would need to talk about the intoxicating and reckless abandon of youth. It’s mesmerizing when it’s projected up on the screen in all its glory existing without worldly consequence of any kind.

Miiyo follows Koh and becomes infatuated by his singular passion: a 750cc Kawasaki. But it’s not just a supercharged motorcycle, and it’s not so much about an object made of chrome and an engine. It’s the adrenaline hit and emotional high of riding a motorcycle and riding it fast. It’s almost a dare for life to come at you head-on. For them, living life on on the edge like this is an obvious antidote to the malaise.

It’s both what attracts them to one another and threatens their ultimate undoing. Live fast, die young, has a poetic inevitably to it. I feel like I will need to watch the movie again down the road sometime, but there’s a pervasive sense that this motorbike, this island, this young man and this young woman take on a kind of mythic proportion.

Just like I never caught onto a perceptible rhythm of the monochrome and color, what we witness is not always an objective, tangible world. It exists in the hinterlands of memory, love, passion, and emotions just out of reach. The irony is obvious.

Sometimes, to feel alive, people need to get as close to death as possible. I’m not sure if this star-crossed, high-octane hedonism is still en vogue, but it’s easy to understand how it could seem attractive albeit misguided. There’s a hubris to it.

3.5/5 Stars

The Rocking Horseman (1992)

When I lived in Japan, I was flabbergasted to learn that there was a group that was bigger in Japan during the ’60s than the Beatles. It was The Ventures! This instrumental act kicked off the “Eleki Boom” as their iconic onomatopoeic glissandos (deke-deke-deke) captivated a generation of youth. These teenagers subsequently rushed out to buy their electric guitars and start their own bands during the “Group Sounds” explosion.

Although I didn’t think about it at the time, I’m a sucker for a good musical coming-of-age movie, and this landscape was ripe for such a story. Recently, when I came upon The Rocking Horsemen, I realized a void in the cinematic landscape had been filled thanks to Nobuhiko Obayashi

Fujiwara (Yasufumi Hayashi) feels like the most innocent and congenial of Obayashi’s boy heroes, a Ferris Bueller-type who instantly takes us into his confidence by not only providing voiceover but speaking directly to us.

OB’s films are easily placed in this provincial milieu outside the hustle and bustle of the big city. This gives them a kind of comfortable intimacy, and it’s only a small jump to place them in the past. In this case, Japan during the 1960s. I already mentioned that the movie covers a subgenre I have a private preoccupation with: form-a-band origin stories. That includes That Thing You Do! and Sing Street to The Commitments, Nowhere Boy, and School of Rock. What sets this one apart is the unique context and cultural moment.

Now I’ve been inculcated from an early age that the Beatles had the greatest music, but Fujiwara is coming of age with an ear raised to the admonitions of his elders. Pop music is puerile entertainment, cultural dregs compared to the sophistication of classical music. The Beatles included.

Then, his radio played “Pipeline” and he is changed forever. Any kind of snobbery quickly dissipates. The new sound assaults him as he reclines in his bedroom. There’s no escaping its force, and he converted for good, caught up in the same boom I read about. It was electric liberation.

Since a rock musician can’t look like a Buddhist acolyte, the first course of action was to grow out his hair. It occurs to me that one of the reasons I find these movies compelling is it involves some kind of youthful industry. When you’re young you don’t need to be told the odds. If you want to start a band, and that’s you’re impetus, you can go ahead and do it. No permission is necessary (parents notwithstanding).

In this way, Fujiwara meets his future bandmates. The first shares his interest in rock and turns his back on the more traditional setlist the school club follows. The rest of the members include a priest’s son, who’s the band’s source of worldly wisdom, and then a gawky dork who gets coerced into playing the drums for them.

If initially they fall together organically enough, they also premeditate how to best go about their business. In the end, they resolve to get summer jobs at a local manufacturing plant to save up to buy their instruments. These scenes are mostly transitory — only an end to the means — but as “Woolly Bully” plays over their assembly line, there’s a sense of optimism. They’re getting closer to their goal.

Ittoku Kishibe shows up again after Lonely Heart as a good-natured teacher who supplies American lyrics and ultimately offers to become their club advisor. It’s a small addition, but his tacit affirmation of their endeavors speaks volumes.

I’m fascinated by how pop culture can infiltrate and suffuse through the cracks of a society, especially in an international context. I met Japanese folks with very specified knowledge about Korn or Olivia Newton-John, Sam Cooke, Jazz or Punk music. Or think of the two teens in Mystery Train who go on a pilgrimage to Memphis in search of The King. Where does this come from?

While I wouldn’t call the general Japanese populous particularly aware of world culture, you do find these hyperspecialized niches of expertise. These boys glean their inspirations thanks to radio and import records, even older siblings who pass down a love of Nat King Cole.

A perfect example is Jan and Dean’s “Little Old Lady from Pasadena” played as our hero rides his bike through his neighborhood. It’s a totally different context from the California surf culture I was born and bred in. But it still reaches them on the other side of the world. The same might be said of The Animals, “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.”

It doesn’t feel like a mistake that the first time the new band convenes and brandishes their new name — The Rocking Horsemen — they start playing, and it’s a flawless rendition of “Pipeline” (exactly like the Ventures recording). They make their debut at a show during Christmas with mixed results, but they disregard the critics and play their hearts out. What’s more, they gel and become galvanized as a group. How can you not under the circumstances?

But as school comes to a close, their journey together winds down too. Their first and last big show comes at the annual school cultural festival and with a set list including “I Feel Fine” and “Johnny B. Goode,” they can’t miss. We’ve seen this moment before in many a movie so it’s a kind of expected wish-fulfillment watching them go out.

When you’re an adolescent these are the kind of memories that stay with you. And in a final act of solidarity, Fujiwara now listless and despondent over the future, has his newfound brotherhood to come around him. They christen him their “Bandleader for Life.” So even as their journey as a band might have met its logical conclusion more than an impasse (not many make it like The Beatles), The Rocking Horsemen do have some amount of closure. The music and those relationships will never leave them.

4/5 Stars