It only became apparent to me after the fact that Isle of Dogs sounds quite close to “I love dogs.” You might even say there was a certain amount of forethought in this play on words. However, the pun only works in English as the Japanese pronunciation of the comparable kanji is “Inu ga shima.” Here we have the inherent beauty and simultaneously what some would deem the problematic nature of Wes Anderson’s latest film in a nutshell.

It only became apparent to me after the fact that Isle of Dogs sounds quite close to “I love dogs.” You might even say there was a certain amount of forethought in this play on words. However, the pun only works in English as the Japanese pronunciation of the comparable kanji is “Inu ga shima.” Here we have the inherent beauty and simultaneously what some would deem the problematic nature of Wes Anderson’s latest film in a nutshell.

It’s necessary to lay out how I come at Isle of Dogs because it does contribute to how I perceive it. I’m Japanese-American. I’ve lived in Japan. I know some of the language though it’s an admittedly meager amount. However, I’ve invested in the culture and care about its people and fostering cross-cultural bonds. That’s part of the reason I was drawn to live there for an extended period of time, more than any pop culture infatuation with anime and manga. In those regards, I’m very much American. I also revere Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi and all the rest as most cinephiles do. There you are.

Wes Anderson is someone that I genuinely admire for his aesthetic though I would never necessarily sing his praises needlessly. He doesn’t need me to defend him nor do I look to. Still, when I consider Isle of Dogs I do not see a superficial homage. As with everything he does Anderson’s film feels fairly meticulous and the stop-motion creation is phenomenally precise. Beyond that, it’s infused with Japanese tradition. Certainly, there are markers that some might deem superficial like Taiko or sumo or cherry blossoms (さくら). They are all present.

Thus, I do worry about people who have not interfaced with Japanese culture or the people. Specifically, the character of Tracy (voiced by Greta Gerwig), the foreign exchange student, feels problematic. I’ve met some folks like her where they let their own personalities take control of every situation and there seems to be no sensitivity or give and take.

Because they don’t seem to have any sense of the culture they are in or at the very least they expect others to play by their rules. Hence why many Americans including myself are only fluent in one language. An example springs to mind of Tracy wandering into a bar and hollering at the man behind the counter in English that she wants chocolate milk. Then she berates a Japanese scientist (voiced by Yoko Ono) for not doing anything in opposition to the rampant government corruption. Again, in English.

It was fascinating that I watched the film with an audience where the majority were Japanese so they were not ignorant of their country like Tracy or I might be. But how about viewers in another pocket of the world or even back home where I come from? The audiences saw a different movie altogether with different nuances and connotations.

Some people have noted rightly that a lot of the Japanese dialogue is lost because as the opening disclaimer notes: “The humans in this film speak only in their native tongue (occasionally translated by bilingual interpreter, foreign exchange student, and electronic device). The dogs’ barks are translated into English.” Except for the dogs, that’s a large margin for error.

Even the words of the little pilot, the intrepid boy Atari (voiced by Koyu Rankin) are all but lost on the dogs who don’t speak human and for me as well because, again, my Japanese leaves much to be desired. But the bottom line is that he almost always intuitively knows what the pack of alpha dogs is doing.

They have a connection. He is looking for his faithful guard dog Spots (voiced by Liev Schrieber) who has been cruelly deported by his distant uncle Mayor Kobayashi in his effort to rid the dystopian Japanese city of Megasaki of infectious dogs. Spots was the first of many canines to be deported to the putrid rubbish pile of Trash Island. There you have the film’s plot but it relies on the fact that the boy and the dogs work together.

It goes back to that core tenet of society that dog is man’s best friend. And strip away any amount of visual artistry or cultural layering and that fact remains universal. Kobayashi is a cat person and we surmise his decision was merely a vendetta against canines (going back generations) more than any scientific evidence would suggest.

To be honest, it never feels like Anderson is putting out a giant placard with film references at least not like Tracy with her megaphone. If anything the film conjures up one of Japan’s great national heroes the faithful dog Hachiko. Any traveler to Tokyo will recognize his statue in Shibuya but he is a cultural icon — emblematic of the same bond expressed in this story.

It’s still an Anderson film and as such, I never get emotionally connected with the material (actually maybe I take that back; stop-motion dogs suffering is heartbreaking to watch) nor do I gel with his very personal idiosyncrasies all the time.

But somehow, though the film’s cultural representations and relationship with Japan are flawed, nevertheless it left me more impressed than anything. It seemed like a degree of care was taken. And in the end, this story of canines has moments that unquestionably do resonate with me.

I thought I would have more problems with all the quality voice talent distracting from the story itself and it happened at times where I was stuck on Jeff Goldblum or Bill Murray but more often than not it didn’t seem like one voice stole the show. It was a story that involved many voices.

Some that we are able to understand, others that we can only gather bits and pieces of. But for me personally, rather than that being a deterrent I find it fascinating that the same film can play differently for different audiences and that native Japanese speakers can be in on the movie in a way that I never could.

It’s not that we don’t deserve to know that part of the story necessarily or need to be singled out because we don’t know the language but isn’t that one of the confounding things about culture and language? Oftentimes we don’t understand one another and need to find points of mutual understanding. Things get lost in translation and I think one could make the argument that this happens in Isle of Dogs purposely.

Certainly, Wes Anderson doesn’t know Japanese culture like the back of his hand. In an interview, he said he’s been to Japan some but his references were namely Kurosawa, Miyazaki and the woodblock prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige. And yet if that is true, it still feels as if he’s surrounded himself with some voices different than his own even if his typical ensemble is in place.

We have Kunichi Nomura with input on the script and voice duty for Mayor Kobayashi. More include Akira Takayama, Mari Natsuki, Akira Ito and then better-known names like Nojiro Noda, Yoko Ono, and Ken Watanabe. That’s not to mention the countless other Japanese contributors whose names scrolled by with the end credits.

Admittedly this is only my perception of the film but when I watch it, I never feel like it is assuming the primacy of the English speaking audience or if it is then that assumption gets slyly subverted. I mentioned already that the character of Tracy often speaks in English, in her opposition to Mayor Kobayashi or to the man serving up drinks at the bar counter.

The implicit understanding is that the Japanese characters understand the English being spoken but they choose instead to respond in their native language. So they have met us half way but have we met them? Learning Japanese is difficult, maybe even impractical, but growing our cultural literacy comes in many forms that would only assist in deepening our ties with one another. Only later did I realize that Tracy, the “white savior” as it were, essentially fails in her attempts. If anything she needs the help of an audacious Atari, his guard dog, and the nameless hacker from her school. Without them she is powerless.

As is often the case, certain people use their voices and assertive personalities to push themselves into the limelight unwittingly but those people would be nothing without the taciturn heroes who willingly stay in the periphery until they need to stand up. While Tracy turns me off slightly in fiction and in real life, it’s the others like Atari that resonate with me. Just as the tale of dogs in both camaraderie and loyalty rings a universal note.

However, I realize only now that I didn’t talk much about the actual mechanics and formalistic aspects of the movie but I’ve spoken my peace. Do with it what you will.

3.5/5 Stars

Note: Two articles that I found interesting on this topic were the following: What “Isle of Dogs” Gets Right About Japan and Justin Chang’s Isle of Dogs Review

In some respects, this feels very much like a paint by numbers biopic that takes us through the many paces of such a narrative. The rise, fall, conflict, and self-actualization of our heroes that navigates us to the film’s conclusion.

In some respects, this feels very much like a paint by numbers biopic that takes us through the many paces of such a narrative. The rise, fall, conflict, and self-actualization of our heroes that navigates us to the film’s conclusion. Sufjan Stevens released a song not too long ago as an elegy to Tonya Harding. Being the modern-day folk poet that he is, he cast her as a tragic hero, championing her as a definitive portrait of an All-American girl, larger-than-life, unapologetic, and ultimately beaten back by society at large.

Sufjan Stevens released a song not too long ago as an elegy to Tonya Harding. Being the modern-day folk poet that he is, he cast her as a tragic hero, championing her as a definitive portrait of an All-American girl, larger-than-life, unapologetic, and ultimately beaten back by society at large.

It’s not something you think about often but stoners and film noir fit together fairly well. Why more people haven’t capitalized on this niche is rather surprising. Think about it for a moment. Film noir in the classic sense is known for its private eyes, femme fatales, chiaroscuro cinematography, and perhaps most importantly a jaded worldview straight out of Ecclesiastes.

It’s not something you think about often but stoners and film noir fit together fairly well. Why more people haven’t capitalized on this niche is rather surprising. Think about it for a moment. Film noir in the classic sense is known for its private eyes, femme fatales, chiaroscuro cinematography, and perhaps most importantly a jaded worldview straight out of Ecclesiastes. Entering into the latest Avengers blockbuster I felt like I was missing something thanks to a cold open that places us in an unfamiliar environment. It’s a feeling that has come upon me on multiple occasions previously.

Entering into the latest Avengers blockbuster I felt like I was missing something thanks to a cold open that places us in an unfamiliar environment. It’s a feeling that has come upon me on multiple occasions previously. It only serves to show where my mind goes when I watch a movie. I couldn’t help but think of Harry Chapin’s elegiac and stirringly heart-wrenching tune “Mr. Tanner” as I was ambushed with some of the most revelatory notes of Coco. The most meaningful line out of that song relates how music made our eponymous hero “whole.” I feel the same guttural satisfaction blooming out of this picture.

It only serves to show where my mind goes when I watch a movie. I couldn’t help but think of Harry Chapin’s elegiac and stirringly heart-wrenching tune “Mr. Tanner” as I was ambushed with some of the most revelatory notes of Coco. The most meaningful line out of that song relates how music made our eponymous hero “whole.” I feel the same guttural satisfaction blooming out of this picture. For some Black Panther might be a stellar actioner, consequently, brought to us by a visionary director, Ryan Coogler. It’s top-tier as far as Marvel movies come; there’s little doubt. For others, I completely understand if Black Panther rocks their entire paradigm because there’s so much of note here. The box office seems to confirm that just as much as the dialogue that has been created in its wake.

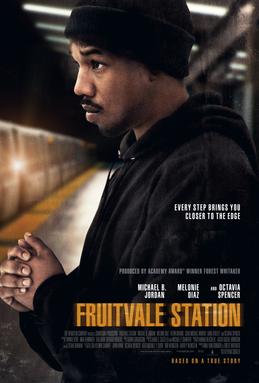

For some Black Panther might be a stellar actioner, consequently, brought to us by a visionary director, Ryan Coogler. It’s top-tier as far as Marvel movies come; there’s little doubt. For others, I completely understand if Black Panther rocks their entire paradigm because there’s so much of note here. The box office seems to confirm that just as much as the dialogue that has been created in its wake. Ryan Coogler is from Oakland, California. He was attending USC Film School in 2009 when Oscar Grant III was shot near the BART station. From those experiences were born his first project. He envisioned Michael B. Jordan in the lead role. Thankfully his vision and the casting came to fruition.

Ryan Coogler is from Oakland, California. He was attending USC Film School in 2009 when Oscar Grant III was shot near the BART station. From those experiences were born his first project. He envisioned Michael B. Jordan in the lead role. Thankfully his vision and the casting came to fruition. My heart lept in my chest when I heard that Taika Watiti (What We Do in The Shadows) was going to be helming the latest Thor movie. Because it’s hardly a well-kept secret that Thor has essentially been the weakest of all the Marvel threads (Hulk’s individual film excluded).

My heart lept in my chest when I heard that Taika Watiti (What We Do in The Shadows) was going to be helming the latest Thor movie. Because it’s hardly a well-kept secret that Thor has essentially been the weakest of all the Marvel threads (Hulk’s individual film excluded).