If Bunuel’s well-remembered adaptation of this material is considerably darker and biting as his pictures always seem to be, then Jean Renoir’s version is fittingly consistent with his own sentiments and oeuvre.

Celestine, as played by the ever precocious Paulette Goddard, looks to be one to tear asunder the stately tranquility of the estate she has been hired to serve at. But in fact what we are met with over time is quite the opposite and that’s one of the great ironies of this film.

Another is the fact that Renoir was called upon to make such a satire under the Hollywood production codes. He is no Bunuel and still, there is a certain anarchy and irreverence that can be taken from many of his native works.

You have only to look at Boudu Saved from Drowning (1932) or is acclaimed masterpiece Rules of the Game (1939) to see the social commentary at work. There is the same upstairs, downstairs dynamic and the pronounced divide between those with means and those who serve those with means.

Paulette Goddard gives a fine showing in the title role that puts her plucky and radiant chambermaid front and center. Whereas she often played opposite a romantic lead like a Chaplin or even Bob Hope, this is her picture and that’s a refreshing change of pace.

What she provides is her usual brand of bodacious energy that carries along her cohort Rose (Irene Ryan) and stands up to the severe and misogynistic valet Joseph (Francis Lederer) who has been in faithful service to the Lanlaire family for 10 years. It sets the tone for the entire picture but it also subsequently reveals that everyone in her vicinity has their own agenda.

There’s Joseph who much like her would love to leave behind his current life for a life of privilege and good fortune. Meanwhile, the controlling Madame Lanlaire (Judith Anderson) wants to use Celestine’s services and certain attributes to help keep her grown son (Hurd Hatfield) at home. She’s suffocated him for an entire lifetime.

The demure, bearded Mr. Lanlaire feels more at ease with Celestine than with his own wife and his feuding next door neighbor the idiosyncratic Captain Mauger (Goddard’s husband and the film’s screenwriter Burgess Meredith) wants to steal Celestine away and hire her on to work at his own estate. He’s even ready to propose marriage and give her nice things if only she’d accept.

So in a sense, if you want to look at the film in very basic terms, Celestine has numerous suitors. One who shares her personal aspirations. One who shares her romantic love. One who makes life a great deal more fun for her and so on. Though only one can end up with her in the end.

It is an admittedly strange circumstance to have a French director of such repute as Renoir directing an English language film from French source material no less. How we ended up with such a project is befuddling. But rather than get caught up in the incongruities it’s suitable to enjoy them for what they are. It could have been a shambles.

I am reminded of Vittorio De Sica’s Terminal Station (1953) that fell under Selznick’s control and was recut and reissued as Indiscretions of An American Wife. The conflicting visions proved to be a disaster.

Here it works to a satisfactory degree. It’s shot and feels like a Renoir film even if the actors themselves or the system they are working in does not. But a Hollywood exterior does not make this film impervious to improprieties. While in some respects it relieves the picture of its claws, there’s nevertheless yet another irony found therein, though the facade must be first pulled away.

It’s so eccentric and giddy with all the flourishes of classical Hollywood and quality supporting actors that it makes us almost forget the strange even indecent behavior that comes to pass. That’s because it’s a Hollywood picture and not a French one.

Furthermore, just because the action is set in France and orchestrated by a French director does not instantly mean that this is a satire of that society alone. Are we so blind as to see the conflicts and relational quibbles that dissect this film as being so far removed from our own?

Surely we don’t have any stratospheres like this or any people with these kinds of behavior in the United States? Charming and unrepressed chambermaids. Brooding men who are bent on vengeance. Mothers willing to use the allure of other women to manipulate their children into still loving them. I can’t speak to any of these things directly but only know we’re often more alike than we would care to admit.

So enjoy Renoir’s Chambermaid on the perfunctory level if you wish. It’s a quirky backroom comedy-drama bolstered by winsome Paulette Goddard. But if you want to see it for something more you may — a satire, a veiled look at risque themes, and anything else you can discern within its frames.

3.5/5 Stars

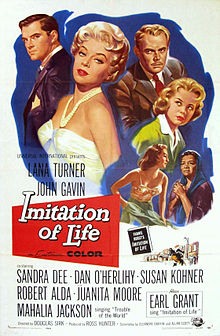

When I was watching the film I distinctly remember one instance I threw my head back in the air and just smiled to myself. How I love Douglas Sirk. He gives us something seemingly so superficial and decadent that plays so perfectly into those expectations and simultaneously steamrolls them with a not-so-veiled indictment unfurled on multiple fronts.

When I was watching the film I distinctly remember one instance I threw my head back in the air and just smiled to myself. How I love Douglas Sirk. He gives us something seemingly so superficial and decadent that plays so perfectly into those expectations and simultaneously steamrolls them with a not-so-veiled indictment unfurled on multiple fronts.