The people making the decisions, at least some of them, undoubtedly knew that this title implied some sort of sordid melodrama, a Douglas Sirk picture anyone? And yet I do admit despite the emptiness in the title, there’s some truth to its implications. Hollywood often is this gaudy, outrageous, maniacal monster looking for people and things to gorge itself on.

Except this is no Sunset Boulevard (1950) or Ace in the Hole (1951) for that matter. It’s not quite as biting or even as tragic or twisted as Wilder’s films but that’s what comes with having Vincente Minnelli at the helm. But rather than critique that decision in any way I think someone like Minnelli thinks about such a picture in a way that Wilder never would. That in itself makes for interesting creative deviations.

First, the camera setups feel impeccable, like a Hitchcock or Ophuls, finding the perfect moments to bring attention to a shot and the precise instances to sit back and allow things to unfold. It’s utilizing a bit of a flashy framing device like a Letter to Three Women (1949) or All About Eve (1950) but in this case, it relates the story of one Hollywood producer through the eyes of the people who worked with him.

Jonathan Shields (Kirk Douglas) is a man whose father was one of the most hated men in Hollywood and also one of the most successful. Jonathan buries his father and with hardly a penny to his name looks to rise out of the ashes his dad left behind. He just might make good too. So as such, it’s another exploration of Hollywood top to bottom, starting very much at the bottom.

That’s part of what makes this story compelling as we watch an ambitious man claw his way from poverty row and B pictures using a joint partnership with another up-and-comer (Barry Sullivan) to slide his way into a gig as a big-time producer. It’s at these beginning stages where they succeed in making a name for themselves under producer Harry Pebbel (Walter Pidgeon).

For Sullivan, he is so closely tied to the business, it’s almost as if he’s wedded to the picture industry. It’s both his life and obsession every waking hour. So when he’s done with one and waiting for the next he has what can best be termed, “the after picture blues.” He’s still trying to adopt his philosophy for women and apply it to his films — love them and leave them.

In passing, we get an eye into the bit players and the small-timers working behind the scenes just to make a decent day’s wage whether assistants or agents or pretty starlets moonlighting as companions at night. There’s even a very obvious current of sexual politics where women are naturally assumed to be at the beck and call of any higher up to pay them any favors. It’s the grimy, sleazy side of the business that continues to reveal itself in due time with connivers and drunks and suicidal wretches conveniently hidden by bright lights and trick photography.

Further still, there are screen tests, meetings, rushes, and sound stages, makeup artists, and costume designers each a part of the unwieldy snake that makes up a film production. All the nitty-gritty that we conceive to be part of the movie-making whirly gig churning out pictures each and every year. They say if it’s not broke then don’t fix but what if it is broken and no one is fixing it? I write this right in the wake of Harvey Weinstein’s ousting due to a laundry list of accusations against him.

One of those involved in this beast receives a stellar introduction of her own. We meet Georgia Lorrison (Lana Turner) with her feet hanging down from the eaves of an old mansion that belonged to her deceased father. She like Shields comes from Hollywood royalty and she like him is also looking to get out of her father’s shadow.

Jonathan is derisively called “Genius Boy” and maybe he is but opportunistic might be a more applicable term. Still, when he makes his mind up, he cannot be stopped and when he deems this smalltime actress will be his next star, he makes it so.

The same goes for novelist turned screenwriter James Lee Bartlow (Dick Powell) who Jonathan is able to coax out to Hollywood albeit reluctantly and works his magic to get him to stay along with his southern belle of a wife (Gloria Grahame) who is completely mesmerized by this magical land out west. Again, Jonathan turns his new partnership into a lucrative success but not without marginalizing yet another person.

One of the most interesting suggestions made by the film is not how much Jonathan ruined his collaborators — alienated them yes — but he really helped their careers. In some ways, it reflects what happens with great men who are lightning rods and always thinking about the next big thing. They’re obsessed with ideas and connections, finding those relationships that will lead to power, wealth, acclaim, and awards. Any amount of honest-to-goodness friendship goes out the window.

But for all those who felt slighted, there’s almost no need to feel truly sorry for them because they bought into this industry with its promises and they bit into the fruit. Sure, their feathers got ruffled and their egos bruised but it goes with the territory.

For everything we want to make it out to be, it’s a tooth and claw operation and those who get ahead usually are the most ruthless of the bunch. Whether we should feel sorry for them or not is up for debate. But maybe we should because a mausoleum full of Academy Awards means nothing. A life of power will be ripped from you the day you die as will the wealth, elegance, and extravagance. It will all be gone. Then, you’re neither bad nor beautiful. You’re simply forgotten. In that respect, this films has meager glimpses of a Citizen Kane (1941) or even real-life figures like Orson Welles and David O. Selznick.

Except in the sensitive hands of Minnelli, this picture is neither an utter indictment of Hollywood nor does it take a complete nosedive in showing how far the man has fallen. It even reveals itself in the performance of Kirk Douglas who while still brimming with his usual intensity chooses to channel his character more so through the vein of charisma.

So if we cannot love or admire his dealings there’s still a modicum amount of respect we must hold for him. Everyone comes out with a shred of dignity and the film’s end is more lightly comic than we have any right to suppose. But then again, we’re not in the moviemaking business and they are.

4.5/5 Stars

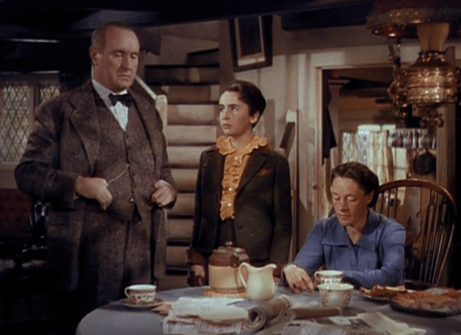

In the recent days, I gained a new appreciation of June Allyson as a screen talent and in her own way she pulls off Jo March quite well though it’s needlessly difficult to begin comparing her with Katharine Hepburn or Winona Ryder.

In the recent days, I gained a new appreciation of June Allyson as a screen talent and in her own way she pulls off Jo March quite well though it’s needlessly difficult to begin comparing her with Katharine Hepburn or Winona Ryder.

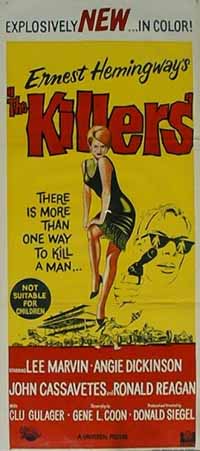

After an opening to rival the original film noir The Killers (1946), though nowhere near as atmospheric, Don Siegel’s The Killers asserts itself as a real rough and tumble operation with surprisingly frank violence. However, it might be expected from such a veteran action director on his way to making Dirty Harry (1971) with Clint Eastwood.

After an opening to rival the original film noir The Killers (1946), though nowhere near as atmospheric, Don Siegel’s The Killers asserts itself as a real rough and tumble operation with surprisingly frank violence. However, it might be expected from such a veteran action director on his way to making Dirty Harry (1971) with Clint Eastwood. We’re all part monsters in our subconscious. ~ Leslie Nielsen as Commander Adams

We’re all part monsters in our subconscious. ~ Leslie Nielsen as Commander Adams Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and Cool Hand Luke (1967) were two films that took a fairly extensive look at what a chain gang actually was in cinematic terms. Meanwhile, Sam Cooke’s eponymous song made almost in jest has added another layer to the tradition.

Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and Cool Hand Luke (1967) were two films that took a fairly extensive look at what a chain gang actually was in cinematic terms. Meanwhile, Sam Cooke’s eponymous song made almost in jest has added another layer to the tradition.