There’s something remarkably moving about the beginning of Saving Private Ryan. I’ve only felt it a few times in my own lifetime whether it was family members recognizing names on the Vietnam Memorial tears in their eyes or walking over the sunken remains of the U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbor. It’s these types of memories that don’t leave us — even as outsiders — people who cannot understand these historical moments firsthand.

There’s something remarkably moving about the beginning of Saving Private Ryan. I’ve only felt it a few times in my own lifetime whether it was family members recognizing names on the Vietnam Memorial tears in their eyes or walking over the sunken remains of the U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbor. It’s these types of memories that don’t leave us — even as outsiders — people who cannot understand these historical moments firsthand.

And that’s why Saving Private Ryan is a truly breathtaking, at times horrifying, and wholly visceral experience. Words cannot actually describe the visuals on the beaches of Normandy at Omaha. The utter chaos, death, and tumult engulfing the scene — above and below the surface of the water.

The cast includes a number of memorable players including Tom Hanks, Barry Pepper, Giovanni Ribisi, Vin Diesel, Paul Giamatti, Matt Damon, and even Nathan Fillion. And yet it’s not about any one man or even a singular act of valor. Even Private Ryan is only a starting point of a far more universal tale.

It’s also easy to say that this is a film cheapens life in the number of bodies that are blown to bits and slaughtered seemingly needlessly on screen. However, it’s even more difficult to acknowledge that in one sense life is cheap — transient to the extent that our bodies are not indestructible. We are fallible beings and breath so easily leaves our lungs and no time is this more evident than in the wake of war.

One sequence that springs to mind involves two surrendering men who, on first inspection, look German and sound German. The men under Captain Miller’s (Tom Hanks) command gun them down and they do it with smiles on their faces. This, after all, is the enemy, pure and simple. Except they were not “Nazis.” They weren’t even Germans, but Czechs (based on what they say). Men who historically had been captured by the Nazis and press-ganged into military service. And in the end, they get shot by Americans. Even the undertones of this scene point to the fact that their lives were so easily snuffed out, without even a second thought.

So, yes, life seems cheap in this film in the physical sense, even from just one example. But it is granted a great deal of depth and richness in many other ways. Families and brothers. Comrades and compatriots. Personal convictions and disillusionment in war revealed through the many characters we come to know. All of that bleeds out of this film along with the blood from the bodies.

In that sense, it’s all difficult to watch and Spielberg never intended this to be easy going. I cannot speak for others but within the intense moments of bloodshed, the lulls in the action, and unrest within the ranks, there’s a solemnity developed.

War is at times the everyday. It’s indescribable and inscrutable. But Saving Private Ryan’s suggests that there are certain things that we hold onto. High and lofty things such as liberty and freedom that are often so easy to discount. They seem easily besmirched, dragged through the mud by all of our human inadequacies and evil. But perhaps that makes them even more important to hang on to, because just like life, these ideals are worth the fight, though they might so easily be lost. It doesn’t make the wrong right or cover up all the pain, even found within this film, but it latches on a tiny bit of good within a whole lot of messiness.

It goes back to the basic implications of the film’s main conceit — the task of saving one man — Private James Francis Ryan (Matt Damon). It’s representative of not only the entire war but each and every one of us as we traverse roads of tribulation. Every story, whether wartime or our own, deserves an ending with some type of salvation. Because Saving Private Ryan is imbued with so much more meaning. Our human experience is wrapped up in it. There is no greater love than a man giving his life for his friends. But imagine if you are dying for the freedom of others or even the preservation of someone who you hardly know? That’s what happens in this story.

That’s why when elderly James Ryan comes back to Normandy so many years later, there’s a gravity to the situation. This is by no means a corny piece of Hollywood drama. It’s the ultimate act of love that he has received and he can hardly comprehend it, just as we as an audience must grapple with it too. In that way, Saving Private Ryan is indubitably affecting not simply as a war drama but an epic human narrative. It pertains to all of us.

The profound and terrifying thing about this gift that he has received through the sacrifice of so many others is that he cannot “earn it.” Because, in this sense, life proves to be far from cheap. There is no way to earn that back. There is no way for us to live a wholly “good” life or be completely “good” people. The whole entirety of the film tells us otherwise. Still, we can live our life with a sense of freedom knowing that cannot be expected of us. A life of purpose is all that can be asked of us. It’s that kind of purpose that makes Saving Private Ryan continuously compelling.

5/5 Stars

The Birds is about all sort of birds. The ones we are acquainted with initially are actually a pair of humans. Lovebirds you might call them. Except they don’t know it quite yet, but the moment Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren) and Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor) meet in a pet shop, the sparks are already flying — the birds too.

The Birds is about all sort of birds. The ones we are acquainted with initially are actually a pair of humans. Lovebirds you might call them. Except they don’t know it quite yet, but the moment Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren) and Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor) meet in a pet shop, the sparks are already flying — the birds too. Most assuredly, the film benefits from long stretches of wordless action. The most striking example involves a murder of crows gathering on a jungle gym near the schoolhouse. Never before was the name of their posse more applicable. And while the narrative lacks a true score, the unnerving screeches from the birds is sound enough to send chills down the spine of any audience.

Most assuredly, the film benefits from long stretches of wordless action. The most striking example involves a murder of crows gathering on a jungle gym near the schoolhouse. Never before was the name of their posse more applicable. And while the narrative lacks a true score, the unnerving screeches from the birds is sound enough to send chills down the spine of any audience. The Greek gods created a woman – Pandora. She was beautiful and charming and versed in the art of flattery. But the gods also gave her a box containing all the evils of the world. The heedless woman opened the box, and all evil was loosed upon us.

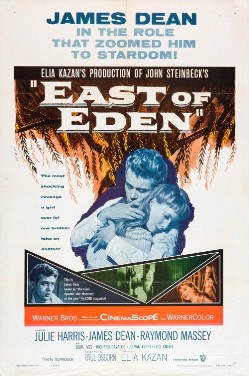

The Greek gods created a woman – Pandora. She was beautiful and charming and versed in the art of flattery. But the gods also gave her a box containing all the evils of the world. The heedless woman opened the box, and all evil was loosed upon us. East of Eden. It was John Steinbeck’s epic work. Showcasing a familial narrative sprawled across his familiar locales of Salinas and Monterey over the turn of the century. But as a film, it rather unwittingly became James Dean’s. He wasn’t even a star yet. He had been on the stage and in a few small roles on television. His performance as Cal Trask was his first film role and the only one that ever got released during his lifetime. As his following two films, both premiered after his untimely death (curiously not all that far away from this film’s setting).

East of Eden. It was John Steinbeck’s epic work. Showcasing a familial narrative sprawled across his familiar locales of Salinas and Monterey over the turn of the century. But as a film, it rather unwittingly became James Dean’s. He wasn’t even a star yet. He had been on the stage and in a few small roles on television. His performance as Cal Trask was his first film role and the only one that ever got released during his lifetime. As his following two films, both premiered after his untimely death (curiously not all that far away from this film’s setting). Are you leaving room for Jesus?~Amanda

Are you leaving room for Jesus?~Amanda

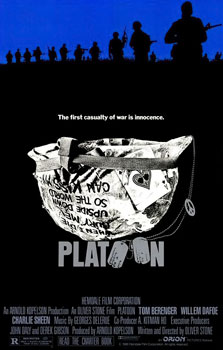

It’s a rather interesting parallel that Charlie Sheen is playing much the same role his father did in Apocalypse Now. At least in the sense that they become our entry point into the mire of war, specifically in Vietnam. But where Apocalypse seemed to belong more so to Brando or even Duvall, Platoon is really Willem Dafoe’s film. At least he’s the one who makes it what it is. His final moment is emblematic of the entire narrative.

It’s a rather interesting parallel that Charlie Sheen is playing much the same role his father did in Apocalypse Now. At least in the sense that they become our entry point into the mire of war, specifically in Vietnam. But where Apocalypse seemed to belong more so to Brando or even Duvall, Platoon is really Willem Dafoe’s film. At least he’s the one who makes it what it is. His final moment is emblematic of the entire narrative. Fallen Idol is a fascinating film for how it develops inner turmoil. It’s earnestly interested in the point of view of a child and as such, it functions on multiple levels –that of both kids and adults. Philippe’s (Bobby Henrey) home is the embassy as his father is a French ambassador who is always away on the job. So Phil’s a little boy who is perpetually in the care of servants. Namely the authoritarian Mrs. Baines (Sonia Dresdel) and her good-natured husband (Ralph Richardson).

Fallen Idol is a fascinating film for how it develops inner turmoil. It’s earnestly interested in the point of view of a child and as such, it functions on multiple levels –that of both kids and adults. Philippe’s (Bobby Henrey) home is the embassy as his father is a French ambassador who is always away on the job. So Phil’s a little boy who is perpetually in the care of servants. Namely the authoritarian Mrs. Baines (Sonia Dresdel) and her good-natured husband (Ralph Richardson).