Like any self-respecting film noir, it opens with men whaling on each other amid stylized darkness. Edward Dmytryk’s Crossfire is an issue-driven picture and it’s an important one given the cultural moment in which it came into being. There’s no doubting that.

But though the imagery is spot on and we have numerous noir regulars, it doesn’t feel like a noir film in the semi-conventional sense. Maybe it’s because the issue it was looking to root out takes precedence over any of its more formalistic qualities and that’s perfectly fine.

From a practical standpoint, Dymytrk opted to shoot the film with low key lighting as it’s a cheaper set-up and also a lot quicker which allowed the picture to be churned out in a mere 20 days. However, it’s still quite befuddling how a film this short can still somehow be incomprehensible at times.

Like any good procedural it whips out a long list of characters introduced in every sequence who either have significant amounts of screentime or show up for a few moments and still manage to play a crucial part in this obscured piece of drama.

Realistically, Crossfire can be touted as the film of the three Roberts: Young, Ryan, and Mitchum. Robert Young will always be heralded as a television father much like Hugh Beaumont and so while I can never take him quite seriously in such a role as a police investigator, he certainly doesn’t do a poor job as Captain Finlay.

Paradoxically, Robert Ryan is one of those actors who is probably grossly underrated and yet as far as personal taste goes I’ve never liked him much (Though my esteem steadily rises). Maybe that simply pertains to the kind of characters he often played such as the belligerent Montgomery in this film. They are not meant to be affable and he does a wonderful job of eliciting a scornful reaction.

Likewise, Robert Mitchum has arguably the least important role of the three, but he still has that laconic magnetism that wins us over, portraying one of the other soldiers caught up in this whole big mess. Sgt. Peter Keeley is a bit of a tough guy but also ready to watch the back of his brothers in arms. He’s our counterpoint to Robert Ryan.

The minor players list out like so. The victim of it all was a man named Samuels (Sam Levene) who crossed paths with the demobilized soldiers in a bar and seemed nice enough. He even struck up a conversation with a homesick G.I. named Mitch (George Cooper) who Keeley guesses might be a prime suspect for murder.

Jacqueline White is the wanted Corporal’s concerned spouse while Gloria Grahame plays a characteristic noir dame who might prove to be an invaluable witness on his behalf, if only she’ll cooperate.

This is yet another link in the chain of post-war crime pictures where soldiers were returning home only to meet a new kind of disillusionment (ie. The Blue Dahlia or Act of Violence). A certain bar scene played over from multiple perspectives proves to be a pivotal moment, but it’s full of fuzzy recollections and screwy bits of information. No one seems quite sure what happened and the film banks on this ambiguity.

However, it’s about time to cease skirting around the obvious and say outright what the film is an indictment of. It’s anti-Semitism. “Jew-boy” is the trigger word. Though the film requires some reading between the lines, thanks to the production codes, there’s no context needed to understand what that means. It’s instantly apparent bigotry is rearing its ugly head.

As such, Crossfire shares a similar conviction with the year’s other famed issue-driven picture The Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) and it brings to mind the wartime short film headlined by Frank Sinatra, The House I Live In (1945).

But, of course, when you begin to analyze one group of people there always seem to be others still being marginalized whether Japanese-American, African-American, Mexican-American. You name it. And that’s part of what makes such a portrait fascinating. To see to what extent the lines of inclusion will be drawn up.

Though it’s evident that he’s preaching, there are still some steadfast truths coming from Robert Young as he tries to convince a soldier (William Phipps), still wet behind the ears, what he must do for the sake of his conscience. There’s a need to stand up to the bigots because hate is always the same. They hated the Irish and the Italians before just like they will continue to hate some other people group in years to come.

Even if the history gets pushed to the fringes and it doesn’t get taught in school, that doesn’t make it any less of the truth or any less of our history. It’s possible to contend that we are made stronger, not weaker when our troubled history and past indiscretions are fully acknowledged. Only then can we learn, heal the wounds, and pursue a better future together.

So Murder, My Sweet (1944) is still a superior film noir from Edward Dmytryk and probably a great deal more fun, but there’s no denying the message that’s at work behind Crossfire.

3.5/5 Stars

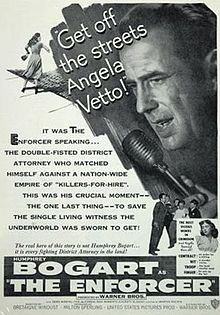

Not that this should deter you completely but The Enforcer isn’t a particularly unique crime film by any stretch of the imagination. Still, we have Humphrey Bogart headlining the police procedural not unlike a Call Northside 777 (1948), The Naked City (1948), or Panic in the Streets (1950).

Not that this should deter you completely but The Enforcer isn’t a particularly unique crime film by any stretch of the imagination. Still, we have Humphrey Bogart headlining the police procedural not unlike a Call Northside 777 (1948), The Naked City (1948), or Panic in the Streets (1950).

Like a Cry Danger (1951) or a Private Hell 36 (1954), this low budget film noir flick is such a joy to watch because it wears what it is right on its sleeve, clear out in the open. What we get is an utterly absurd paranoia thriller that also happens to be a heaping plate of B-noir fun.

Like a Cry Danger (1951) or a Private Hell 36 (1954), this low budget film noir flick is such a joy to watch because it wears what it is right on its sleeve, clear out in the open. What we get is an utterly absurd paranoia thriller that also happens to be a heaping plate of B-noir fun.