“He spat on Balzac!”

“He spat on Balzac!”

Jean Renoir always had a preoccupation with class divides and Boudu showcases that same blatant juxtaposition of class, or more precisely, the lifestyles of the middle class versus a lowly tramp. Except in this specific instance, the tramp (the indelible Michel Simon) could care less about the gap. He thumbs his nose at any charity and makes no effort to conform to the reins put on him by the reputable of middle-class society.

The man who steps to the fore is a middle-aged married bookkeeper who has the hots for his housekeeper. With his wandering spyglass, he spots the hapless Boudu jump into the Seine. From that point, he leaps into action toddling out to the street followed by the crowds of onlookers. He’s the first to plunge himself into the depths to bring the unfortunate soul to safety, and his middle-class brethren laud him for his supreme act of charity. But Monsieur Lestingois does not stop there, insisting that the wretched man be brought to his nearby flat.

Soon Boudu is wrapped up in middle-class luxury that he didn’t ask for, at the behest of Edouard who takes an initial liking to this bushy-haired man he happened upon. After all, he is intent on playing savior and Boudu obliges. It’s in these forthcoming scenes that Renoir examines class in a satirical way, feeling rather like a precursor to some of Bunuel’s later work, without the religious undertones. And yet for some reason, we cannot help but like Boudu a lot more. True, he is loud, messy, rude and unruly, but there’s something undeniably charming about his life philosophy. There are no pretenses or false fronts. He lets it all hang out there. In this regard, Michel Simon is the most extraordinary of actors, existing as a caricature with seemingly so little effort at all. He steals every scene whether he’s propped up between two door frames or cutting out a big swath of his beard for little reason.

Soon Boudu is wrapped up in middle-class luxury that he didn’t ask for, at the behest of Edouard who takes an initial liking to this bushy-haired man he happened upon. After all, he is intent on playing savior and Boudu obliges. It’s in these forthcoming scenes that Renoir examines class in a satirical way, feeling rather like a precursor to some of Bunuel’s later work, without the religious undertones. And yet for some reason, we cannot help but like Boudu a lot more. True, he is loud, messy, rude and unruly, but there’s something undeniably charming about his life philosophy. There are no pretenses or false fronts. He lets it all hang out there. In this regard, Michel Simon is the most extraordinary of actors, existing as a caricature with seemingly so little effort at all. He steals every scene whether he’s propped up between two door frames or cutting out a big swath of his beard for little reason.

In the meantime, he wears their clothes and eats their food, but he doesn’t have to concede to their rules. Boudu ends up winning the lottery of 100,000 francs, while unwittingly stealing away his esteemed benefactor’s unhappy wife. Whereas Boudu has the audacity to do the unthinkable out in plain view, he’s perhaps the most brutally honest character in the film. Everyone else veils their vices and hides their true intentions behind good manners and closed doors. But there has to be a point where all parties involved are outed and the moment comes when husband and wife simultaneously catch each other.

Charity in a sense is met with scorn, but it feels more nuanced than, say, Bunuel’s Viridianna (1961). In many ways, Boudu seems like a proud individual or at least an independent one. He hardly asks for the charity of the wealthy, and he’s content with his lot in life, even to the extent of death. It’s also not simply chaos for the sake of it, and he hardly lowers himself to the debauchery of Bunuel’s unruly bunch. Still, he obviously rubs the more civilized classes the wrong way, by scandalizing their way of life and trampling on their social mores without much thought. It’s perfectly summed up by the last straw when a fuming Edouard incredulously exclaims, “He spat on Balzac.” The nerve!

Charity in a sense is met with scorn, but it feels more nuanced than, say, Bunuel’s Viridianna (1961). In many ways, Boudu seems like a proud individual or at least an independent one. He hardly asks for the charity of the wealthy, and he’s content with his lot in life, even to the extent of death. It’s also not simply chaos for the sake of it, and he hardly lowers himself to the debauchery of Bunuel’s unruly bunch. Still, he obviously rubs the more civilized classes the wrong way, by scandalizing their way of life and trampling on their social mores without much thought. It’s perfectly summed up by the last straw when a fuming Edouard incredulously exclaims, “He spat on Balzac.” The nerve!

The ultimate irony is that Boudu ends up in the water once again, and he’s not the only one this time. This also serves to take Renoir back into his element, because he’s always at his best in the great outdoors where the natural beauty of parks and rivers become his greatest ally in his misc en scene. Still, his framing of shots always gives way to a beautiful overall composition inside and out. Boudu is no different. You simply have to sit back and enjoy it like a pleasant outing on the Seine.

4/5 Stars

As I’ve grown older and, dare I say, more mature, I like to think that I’ve gained a greater appreciation for those moments when I don’t understand, can’t comprehend, and am generally ignorant. Now I am less apt to want to beat myself up and more likely to marvel and try and learn something anew. Thus, Marienbad is not so much maddening as it is fascinating. True, it is a gaudy enigma in form and meaning, but it’s elaborate ornamentation and facades easily elicit awe like a grandiose cathedral or Renaissance painting from one of the masters. It’s a piece of modern art from French director Alain Resnais and it functions rather like a mind palace of memories–a labyrinth of hollowness.

As I’ve grown older and, dare I say, more mature, I like to think that I’ve gained a greater appreciation for those moments when I don’t understand, can’t comprehend, and am generally ignorant. Now I am less apt to want to beat myself up and more likely to marvel and try and learn something anew. Thus, Marienbad is not so much maddening as it is fascinating. True, it is a gaudy enigma in form and meaning, but it’s elaborate ornamentation and facades easily elicit awe like a grandiose cathedral or Renaissance painting from one of the masters. It’s a piece of modern art from French director Alain Resnais and it functions rather like a mind palace of memories–a labyrinth of hollowness. In fact, although this film was shot on estates in and around Munich, I have been on palace grounds similar to the film. There’s something magnificent about the sprawling wide open spaces and immaculate landscaping. But still, that can so easily give way to this sense of isolation, since it becomes so obvious that you are next to nothing in this vast expanse. Marienbad conveys that beauty so exquisitely, while also paradoxically denoting a certain detachment therein.

In fact, although this film was shot on estates in and around Munich, I have been on palace grounds similar to the film. There’s something magnificent about the sprawling wide open spaces and immaculate landscaping. But still, that can so easily give way to this sense of isolation, since it becomes so obvious that you are next to nothing in this vast expanse. Marienbad conveys that beauty so exquisitely, while also paradoxically denoting a certain detachment therein. Do we understand this bit of interaction at this stately chateau? Probably not. In fact, I’m not sure if we are meant to know the particulars about last year in Marienbad. That doesn’t mean we still can’t enjoy it for what it is. Because Alain Resnais is perennially a fascinating director and he continued to be for many years. Whether you think this is a masterpiece or a piece of rubbish at least give it the courtesy and respect it is due. Then you can pass judgment on it, whatever it may be.

Do we understand this bit of interaction at this stately chateau? Probably not. In fact, I’m not sure if we are meant to know the particulars about last year in Marienbad. That doesn’t mean we still can’t enjoy it for what it is. Because Alain Resnais is perennially a fascinating director and he continued to be for many years. Whether you think this is a masterpiece or a piece of rubbish at least give it the courtesy and respect it is due. Then you can pass judgment on it, whatever it may be. Arguably the greatest French comic was Jacques Tati and like Chaplin or Keaton he seemed to have an impeccable handle on physical comedy, combining the human body with the visual landscape to develop truly wonderful bits of humor. Bed and Board is a hardly a comparable film, but it pays some homage to the likes of Mon Oncle and Playtime. There’s a Hulot doppelganger at the train station, while Antoine also ends up getting hired by an American Hydraulics company led by a loud-mouthed American (Billy Kearns) who closely resembles one of Hulot’s pals from Playtime. Furthermore, there are supporting cast members with a plethora of comic quirks. The man who won’t leave his second story apartment until Petain is dead and buried at Verdun. No one seems to have told him that the old warhorse has been dead nearly 20 years. The couple next door that is constantly running late, the husband pacing in the hallway as his wife rushes to make it to his opera in time. There’s the local strangler who is kept at arm’s length until the locals learn something about him. The rest is a smattering of characters who pop up here and there at no particular moment. Their purpose is anyone’s guess, and yet they certainly do entertain.

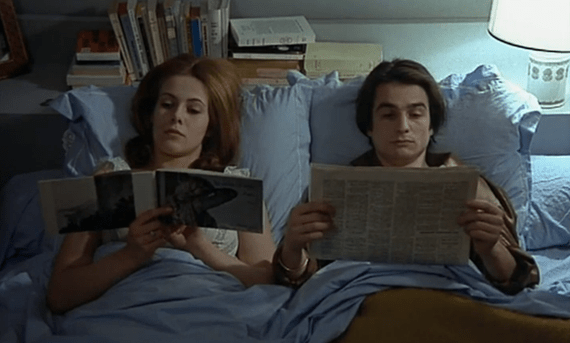

Arguably the greatest French comic was Jacques Tati and like Chaplin or Keaton he seemed to have an impeccable handle on physical comedy, combining the human body with the visual landscape to develop truly wonderful bits of humor. Bed and Board is a hardly a comparable film, but it pays some homage to the likes of Mon Oncle and Playtime. There’s a Hulot doppelganger at the train station, while Antoine also ends up getting hired by an American Hydraulics company led by a loud-mouthed American (Billy Kearns) who closely resembles one of Hulot’s pals from Playtime. Furthermore, there are supporting cast members with a plethora of comic quirks. The man who won’t leave his second story apartment until Petain is dead and buried at Verdun. No one seems to have told him that the old warhorse has been dead nearly 20 years. The couple next door that is constantly running late, the husband pacing in the hallway as his wife rushes to make it to his opera in time. There’s the local strangler who is kept at arm’s length until the locals learn something about him. The rest is a smattering of characters who pop up here and there at no particular moment. Their purpose is anyone’s guess, and yet they certainly do entertain. But as Truffaut usually does, he digs into his character’s flaws that suspiciously look like they might be his own. Antoine easily gets swayed by the demure attractiveness of a Japanese beauty (Hiroko Berghauer), and he begins spending more time with her. Thus the marital turbulence sets in thanks in part to Antoine’s needless infidelity –revealed to Christine through a troubling bouquet of flowers. It’s hard to keep up pretenses when the parent’s come over again and Doinel even ends up calling on a prostitute one more. It’s as if he always reverts back to the same self-destructive habits. He never quite learns.

But as Truffaut usually does, he digs into his character’s flaws that suspiciously look like they might be his own. Antoine easily gets swayed by the demure attractiveness of a Japanese beauty (Hiroko Berghauer), and he begins spending more time with her. Thus the marital turbulence sets in thanks in part to Antoine’s needless infidelity –revealed to Christine through a troubling bouquet of flowers. It’s hard to keep up pretenses when the parent’s come over again and Doinel even ends up calling on a prostitute one more. It’s as if he always reverts back to the same self-destructive habits. He never quite learns. Charles Trenet’s airy melody “I Wish You Love” is our romantic introduction into this comedy-drama. However, amid the constant humorous touches of Truffaut’s film, he makes light of youthful visions of romance, while simultaneously reveling in them. Because there is something about being young that is truly extraordinary. The continued saga of Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel is a perfect place to examine this beautiful conundrum.

Charles Trenet’s airy melody “I Wish You Love” is our romantic introduction into this comedy-drama. However, amid the constant humorous touches of Truffaut’s film, he makes light of youthful visions of romance, while simultaneously reveling in them. Because there is something about being young that is truly extraordinary. The continued saga of Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel is a perfect place to examine this beautiful conundrum. In fact, all in all, if we look at Doinel he doesn’t seem like much. He’s out of the army, obsessed with sex, can’t do anything, and really is a jerk sometimes. Still, he manages to maintain an amicable relationship with the parents of the innocent, wide-eyed beauty Christine (Claude Jade in her spectacular debut). Theirs is an interesting relationship full of turbulence. We don’t know the whole story, but they’ve had a past, and it’s ambiguous whether or not they really are a couple. They’re in the “friend zone” most of the film and really never spend any significant scenes together. Doinel is either busy tailing some arbitrary individual or fleeing pell-mell from the bosses wife who he has a crush on.

In fact, all in all, if we look at Doinel he doesn’t seem like much. He’s out of the army, obsessed with sex, can’t do anything, and really is a jerk sometimes. Still, he manages to maintain an amicable relationship with the parents of the innocent, wide-eyed beauty Christine (Claude Jade in her spectacular debut). Theirs is an interesting relationship full of turbulence. We don’t know the whole story, but they’ve had a past, and it’s ambiguous whether or not they really are a couple. They’re in the “friend zone” most of the film and really never spend any significant scenes together. Doinel is either busy tailing some arbitrary individual or fleeing pell-mell from the bosses wife who he has a crush on. By the time he’s given up the shoe trade and taken up tv repair he’s already visited another hooker, but Christine isn’t done with him yet. She sets up the perfect meet-cute and the two young lovers finally have the type of connection that we have been expecting. When we look at them in this light, sitting at breakfast, or on a bench, or walking in the park they really do seem made for each other. Their height perfectly suited. Her face glowing with joy, his innately serious. Their steps in pleasant cadence with each other. The hesitant gazes of puppy love.

By the time he’s given up the shoe trade and taken up tv repair he’s already visited another hooker, but Christine isn’t done with him yet. She sets up the perfect meet-cute and the two young lovers finally have the type of connection that we have been expecting. When we look at them in this light, sitting at breakfast, or on a bench, or walking in the park they really do seem made for each other. Their height perfectly suited. Her face glowing with joy, his innately serious. Their steps in pleasant cadence with each other. The hesitant gazes of puppy love.

an anxious Mrs. Carala begins to listlessly comb the streets trying to gather what happened to her lover. Where did he go? Julien

an anxious Mrs. Carala begins to listlessly comb the streets trying to gather what happened to her lover. Where did he go? Julien