Requiem for a Heavyweight was an early live television production that was so popular it garnered a feature-length adaptation a few years later.

It’s relatively easy to see the merits in both because although they enlisted the same director and screenwriter, the actors and the medium do quite a lot to make them feel textured and different. I couldn’t necessarily pick a favorite.

The original is bare-boned but intimate, and there’s a darker more caustic theatricality to the film version. It really comes down to preference. Here are my thoughts on the two versions:

Requiem for a Heavyweight (1956)

This early showcase of the Playhouse 90 live TV format introduced the fragile and most sensitive version of Jack Palance. He’s a hoarse and husky-voiced journeyman boxer named Mountain McClintock.

One of his greatest claims to fame was that he was almost heavyweight champion of the world. But he’s most proud of his integrity. In 111 fights, he never took a dive. That includes his most recent bout. He got pulverized and still managed to make it seven rounds.

Between Rod Serling’s script — the writer called upon his own memories as a one-time boxer — and Palance’s endearing performance, you have the emotional heart of the tale. Because Mountain is proud and principled in his own way. He didn’t get into fighting to murder people or make a ton of money. It’s just the only thing he’s ever known — the only thing he was good at — and he took solace in it.

Now he’s on the way out. The Doc says he’d better quit before he earns more permanent damage. Somehow he’s impressionable like Lenny in Of Mice and Men. Despite his physical presence, he needs protectors and others to look after him. There are certain people in his corner he deeply trusts just as all his words and pearls of wisdom come from the mouths of others.

The real-life familial bond of Keenan and Ed Wynn is equally key because they play the two most important people in Mountain’s life. There’s Maish, his manager, who’s currently in a bit of a bind. Then, Army, his cutman, who’s more resigned to the inevitably around him. He’s seen a lot.

Keenan can exhibit a kind of gruff intensity role to role, but since I know Ed Wynn as such a jovial figure, I almost didn’t recognize him. Both of them exhibit an earnestness in their respective parts. Maish has compromised his integrity and now feels bitter toward Mountain, a has-been fighter he sunk so much time and money into. How is he supposed to get any recompense?

Mountain looks a bit pitiful walking into a job agency with no work experience and a kisser as roughed up as his. However, the attendant behind the desk (Kim Hunter) sees his goodness and drops her business spiel for something more personal.

She responds with heart, tracking him down to his favorite watering hole and vowing to try and help him resurrect his life. The bar serves as the graveyard and burial ground for all the hard-up fighters who wither away inside their own heads. Mountain might easily be headed toward this end and worst yet, he might lose his dignity in service of Maish’s debts…

We must remember what the medium of television accorded the makers. Visually, they were working in fuzzy black and white with tiny boxes of composition but also a more familial viewership. This ultimately impacts the creative choices and the film takes on a hopeful final note.

It’s fascinating to watch the production since it was being taped live and throughout I only noticed one flubbed line rushed over by a mother on the train. Otherwise, around all the orchestrating and simple sets, there’s very little taking us out of the story and disrupting the primary performances. Given the restraints, it’s quite a startling achievement.

3.5/5 Stars

Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962)

Ralph Nelson was the same director who filmed the original TV version. Instantly the big screen is more cinematic thanks to the subjective point of view in the ring. We see a solemn Jackie Gleason, the yelling Mickey Rooney, both standing just outside the ropes.

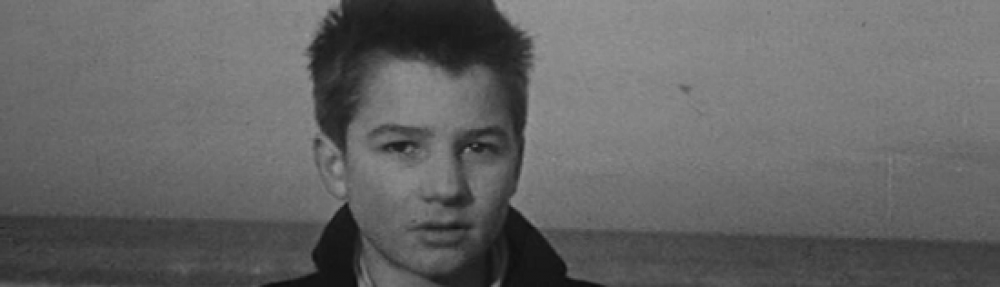

Then, the announcer calls out the name Cassius Clay, and there he is in all his youthful glory beating back the camera! It does feel like a bit of a gimmick, but then we finally see the face of Anthony Quinn battered and bruised and we have our movie.

I assumed the older Gleason was Army and having just recently been introduced to what Mickey Rooney was capable of in The Comedians, it seemed only too reasonable that he would play the more mercurial Maise. How wrong I was.

Quinn seems especially old for his part, but it’s intriguing to see how his character mythology was altered to fit his own Hollywood legacy. Mountain Rivera came out of New Mexico, he ditched school in the 6th grade (instead of 9th), and he’s been fighting longer than Palance’s counterpart. Still, like Palance, Quinn’s larynx sounds like it’s been beaten out of him positively eviscerated by his years of punishment in the ring.

The movie’s milieu is not too far away from The Hustler (also featuring Gleason) or the sensibilities of a TV-to-film scribe like Paddy Chayefsky. The jump to film also means it owns a sharper even more melancholic edge than its small-screen counterpart.

Maish (Gleason) is tailed and tracked out into the ring reminiscent of The Set-Up, and he’s threatened into paying up on his recently accrued debts. He needs the cash fast. Later, he willfully gets his dwindling prize fighter drunk. It’s all part of a ploy to keep him from getting a real job so he can earn money as a sideshow attraction in some trumped up wrestling showcase.

This time it is Julie Harris, who is tasked with helping Mountain turn a new leaf in his life. Her character never shared consequential time with Maish in the original version, but here they share dialogue on a stairwell adding an alternate dynamic to the picture. He says, “The rich get richer and the poor get drunk.” Mountain’s finished, and he’s skeptical of any do-gooder looking to peddle their charity. The edge of cynicism is deeply entrenched.

Also, in the previous rendition, there’s this happy denouement as we recognize Mountain entering into his post-boxing career. It’s possible for him to make something of himself and gain fulfillment beyond the ring by imparting his knowledge to younger generations.

Here it almost feels like the movie has been shifted and the focal point is Maish. Because he is the person who must come to terms with what he has done by totally denigrating Mountain for his own desperate gain.

When he’s marched out into the ring, totally racialized and trivialized, it sears with a level of pain television would have never dared. And we realize all the self-fulfilling prophesies have come true. Mountain really has become the geek, a kind of carnival show attraction, but it’s not out of his own desperation. He’s doing it for someone else. Mountain willfully subjects himself to the ignominy, but Maish is the one who must live with his conscience. I’m not sure what’s worse.

3.5/5 Stars

The action begins with a chase of sorts, except with the men pursuing a buckboard, carrying a woman and a young boy, it’s more like a game of cat-and-mouse. As a Native American maiden and a pretty one at that, they look to have their way with her. A horrible incident follows, and it’s a fairly frank depiction for the 1950s.

The action begins with a chase of sorts, except with the men pursuing a buckboard, carrying a woman and a young boy, it’s more like a game of cat-and-mouse. As a Native American maiden and a pretty one at that, they look to have their way with her. A horrible incident follows, and it’s a fairly frank depiction for the 1950s.