It might be on the nose, but Elvis Presley doing a call and response rendition of “Crawfish” from his balcony with the lady vendor (jazz singer Kitty White) on the street below places us instantly in the movie’s milieu.

It might be on the nose, but Elvis Presley doing a call and response rendition of “Crawfish” from his balcony with the lady vendor (jazz singer Kitty White) on the street below places us instantly in the movie’s milieu.

We’re in the French Quarter of New Orleans, a place blessed with so much musical culture thanks to the Black community. Like many films of the era, they exist on the periphery underrepresented and unappreciated, but they must be acknowledged.

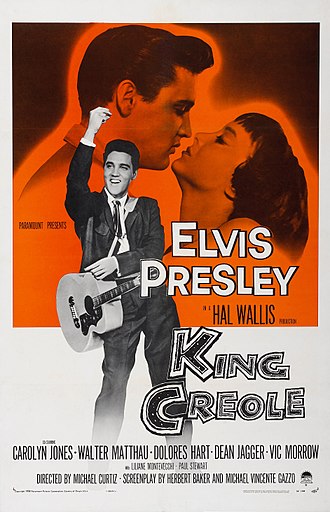

King Creole came out at an earlier juncture in Elvis’s career. He still has license to be himself, and yet the cult of Elvis doesn’t completely overwhelm director Michael Curtiz’s picture. It’s about “The King” in so many ways, yes, but it still has an identity outside of him as a genuinely absorbing story.

His movie career went down hill when everything was about formula and easy cash grabs relying solely on his personality. King Creole actually has substance and danger because it functions as both a vehicle for him and a genuine showcase for his talents and the talents of the actors around him.

Danny Fisher (Elvis) is a teenager who works bussing tables, morning and night, while he tries to squeeze in high school. It’s a tough schedule to maintain, and he’s already failed one year. But his father (Dean Jagger) is out of work so he feels there’s no recourse but to continue in the dive establishment. Danny’s a good kid dealt a tough hand.

It gets even worse one evening when a couple of drunken thugs induce him to sing for them, and then start pushing around one of their lady friends (Carolyn Jones). He comes to her defense, but he has a target on his back and his new female companion causes a mini scandal (and fistfight) on the last day of school. He flunks out again and that’s the end of his short-lived scholastic career.

I feel compelled to bring up Blackboard Jungle because although they’re set in different places, we’re dealing with the same segment of society: struggling working-class teenagers.

You could easily see Elvis in a version of that film especially because it was one of the instigators of the rock ‘n roll craze in movies. King Creole also depicts delinquency though not purely in an instructive sense. We feel like we are watching a movie that’s entertainment first without an attached agenda (aside from banking on Elvis’s stardom before he was drafted into the military).

It evokes the aesthetic of gangster movies of old with Bogart and Cagney, which were directed by Curtiz two decades prior. King Creole has a self-contained world. There’s nothing outside these sets and the interiors that make up the movie. And there’s a sweaty claustrophobia to the tenements and cruddy street corners.

The French Quarter positively oozes with atmosphere, but there’s no way to run away because everyone and everything is tied together. It just so happens that Maxie Fields (Walter Matthau) pulls most of the strings.

The money, economy, and the inertia of almost everyone gravitates in and around the big kahuna. It’s just the way he likes it. He calls for Danny since he’s heard about his voice and his tenacity. Also, Ronnie (Jones) is his girl and he’s a jealous, vindictive man. He likes to keep tabs on what’s his.

Danny takes a job singing at the only spot Maxie doesn’t have his hands in — the modest club King Creole — and he becomes a local hit. Meanwhile, he reluctantly falls in with a few ambitious street hoods led by Vic Morrow. They’re vying to join Maxie’s payroll.

It’s the old story of Danny trying to stay out of trouble, and yet he’s constantly drawn in by want of money and further ashamed of his father’s subservient role as a stooge at the local drugstore. He also starts seeing a pretty shop girl (Dolores Hart). Although his intentions seem far from honorable, there’s still something sympathetic and not fully-formed between them.

All the narrative sinews don’t fit together seamlessly, but I appreciate the dynamics with different actors rubbing up against one another like matchsticks. There is a gritty, operatic quality to it. The music elements are a case and point, allowing us to stretch the parameters of reality just a tinge as Elvis entertains his audience both in-camera and beyond the screen.

Carolyn Jones could be a kind of one note Carmen-like Vamp — the other woman pulling Danny into the web, and she does this, but it’s all in spite of her best efforts. She wants him to get away from Maxie and the same hold the gangster has over her own life. Perhaps in the back of her mind is the hope of some freedom and a life beyond for both of them outside of this private hell.

What can I say about Walter Matthau? It amuses me to even make this comparison because I had never thought about it until this film, but Matthau had a trajectory similar to Bogart’s. Based on how I perceive him in hindsight, I always find it funny he started out as a heavy, and over time he became not only a comic hero but a leading man and a love interest. Here he’s everything despicable and abhorrent about local crime.

Dean Jagger could play characters with such bearing and integrity, and yet in a picture like Bad Day at Black Rock or here, he isn’t squeamish about portraying a bona fide weakling. It’s not a showy part, but there is a sense of bravery to it.

Vic Morrow’s still fairly early in his evolution as he moves on from Blackboard Jungle in the next stage of his dashing hoodlum career. It would be easy to typecast him in the role since it fits so seamlessly.

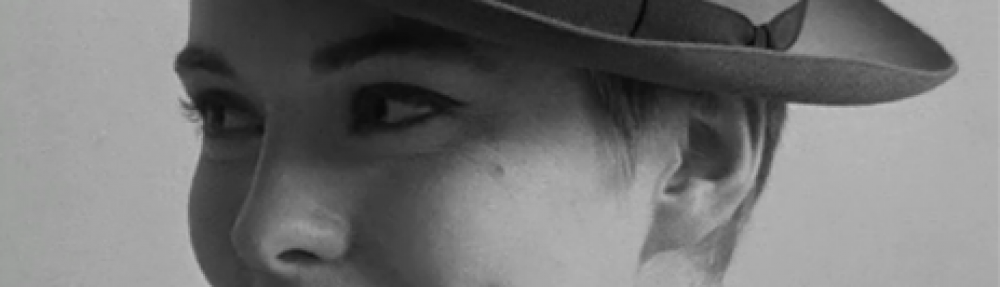

The same might be said of Dolores Hart but for completely different reasons. She embodies the good girl of the movie reminiscent of Eva Marie Saint a few years earlier, representing a reach for something more tender and resolutely decent opposite Brando in On The Waterfront.

Hart’s eyes are always so vibrant even in black & white. I find it fitting when she divulges to Danny about Father Franklin, a man of the cloth she’s known her entire life — someone who’s excited to meet him. And yet Danny’s despondent over his own failings. He cannot bear walking into a church given his current crisis. Nellie represents a level of graciousness to him and of course, Hart famously gave up an ephemeral acting career to become a nun driven by a similar higher calling.

There’s weight to everything Danny does and every mistake comes back to haunt him. His sister (Jan Shepard) strikes up a relationship with the older owner (Paul Stewart) of the King Creole; their relationship also hangs in the balance.

We see Elvis at his most tortured and earnest because he actually gets some material to tear through and try his hand at acting. The part gives him even a small sliver of what Brando had in Waterfront or Dean in Rebel. You can’t put them on the same plane, but then Elvis did what they could never do on the stage with his voice and his pelvis. King Creole is the finest showcase he got to do both in the same film.

The fist fights are pretty epic, and they mean something. Violence is not glorified, but it is an integral and unabashed element of this story. It’s one of the few ways to bring equilibrium to the world.

I’m no pre-germ medical theorist, but a lot of these Classical Hollywood movies seem to function by their own unique humoral theory where you have imbalances of all these different fluid forces at work: the good and the evil, the apathetic and the weak. There’s constant interplay and war between them until finally some kind of stasis is found at the behest of the production code.

The bad is lost and all the abscesses, both corrupt and sullied, are excised until all that’s left in the primordial moral soup is the good. It doesn’t matter how wild the undulations. Finally, our hero is given an existence made up entirely of hope and happiness as everything is brought back into balance.

With the antagonist gone and the promise of a pretty girl’s love, Elvis is able to sing out one final ditty as all the most important people in his life look on with smiles. It’s a classic denouement that doesn’t devalue the seedy sides of humanity. It really is a fine piece of work and it just might be Elvis at his very best. It’s a shame his career took a more insipid trajectory going forward. Because he had so much more to offer beyond a pretty face and peppy music.

3.5/5 Stars

The action begins with a chase of sorts, except with the men pursuing a buckboard, carrying a woman and a young boy, it’s more like a game of cat-and-mouse. As a Native American maiden and a pretty one at that, they look to have their way with her. A horrible incident follows, and it’s a fairly frank depiction for the 1950s.

The action begins with a chase of sorts, except with the men pursuing a buckboard, carrying a woman and a young boy, it’s more like a game of cat-and-mouse. As a Native American maiden and a pretty one at that, they look to have their way with her. A horrible incident follows, and it’s a fairly frank depiction for the 1950s.