Shenandoah is a curious movie on multiple accounts. It’s not unreasonable to think that large families like the Anderson’s existed in real life for mere practicality sake. More children means more farmhands to put in a day’s work and keep things running. It’s a survival tactic.

Shenandoah is a curious movie on multiple accounts. It’s not unreasonable to think that large families like the Anderson’s existed in real life for mere practicality sake. More children means more farmhands to put in a day’s work and keep things running. It’s a survival tactic.

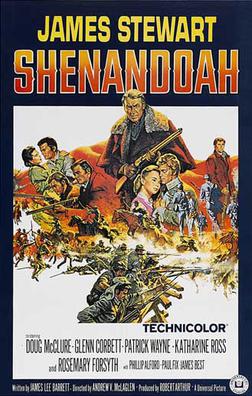

However, this is a Hollywood family loaded to the hilt with handsome young men and pretty women who crowd around the dinner table as their father blesses the food. He believes in hard work and not relying on anyone for anything. That’s why you have so many kids. He also happens to be played by Jimmy Stewart.

His faith is rudimentary. He prays to God and wanders into church conspicuously late on Sundays at the behest of his late wife, but he’s a self-made man who believes in the effectiveness of his own sweat and toil.

The movie also happens to be released near the centennial of the Civil War’s end in 1865. 100 years have passed and there’s still an uneasiness about it. There’s a brand of nobility between a certain class of white man represented especially by George Kennedy in a brief but memorable cameo. These are good men caught up in an ugly conflict, slavery and racism notwithstanding.

But in the same context, there’s only one black man of note and he’s a childhood friend of Anderson’s youngest boy (Phillip Alford most known for To Kill a Mockingbird). Otherwise, Shenandoah doesn’t have much dialogue about the scourge of slavery; perhaps we can be generous and say this not the film’s primary focus. It’s content focusing on its Southern heroes as they attempt to stay out of the fray. It just happens to be against this particular landscape, but its aims are smaller.

Charlie Anderson and his family continue keeping to themselves and working their land. But their Virginia territory is being surrounded by skirmishing Confederate and Union soldiers. It’s inevitable they’re going to have to get involved; they won’t be allowed to sit it out. That’s not how humanity functions. It will affect them in some way.

Although we can see it happening a mile away when the youngest Anderson lad picks up a rebel hat in a stream and starts to wear it around, it’s a necessary choice. He and his buddy Gabriel (Eugene Jackson Jr.) are ambushed near a pond, and he’s taken away as a prisoner of war. In spite of his father’s best efforts, he’s forced to grow up fast and become a man.

While it’s not quite The Searchers, Charlie vows to get him back and he’s intent on finding him even if conditions seem dire. It gives the movie its drive and he and his sons (as well as his daughter played by Rosemary Forsyth) must navigate a treacherous world inflamed by war.

He leaves behind his son (Patrick Wayne) and daughter-in-law (Katharine Ross) to watch over their estate, and we know deep down in the recesses of our beings that no good can come of this. This intuition proves to be correct.

It’s a credit to James Stewart as an actor how he takes a painful if inevitable moment and makes it into something so gut-wrenching. He and the rest of his kids have gone searching for his youngest boy to no avail and they come back empty-handed.

Watching the road on their return is a young Rebel soldier of only 16 and his first reaction is to fire. Jacob Anderson (Glenn Corbett) is instantly killed, slumped in his saddle.

The boy is shocked and Stewart comes upon him with the seething rage pent up from all his Anthony Mann pictures. He’s going to kill the boy for what he’s done. He’s got him in his grips and for a split second he’s choking him to death in a surreal out-of-body experience. The emotion has overtaken him.

Then, he realizes what he’s doing and with anger still smoldering and tears almost welling in his eyes, he tells the boy he wants him to grow up and have children so that one day when someone kills one of them, he’ll know what it feels like.

Stewart elevates this scene into this galling interaction between two people that’s somehow vindictive and still heartbreaking. Because it’s the rage Stewart was always capable of in his Westerns, but this time he’s a father with the unconditional love that comes with such a distinction. He loves his children so deeply just as he loved his wife. It’s the root of all his fury.

When they sit down before the table to pray again, it’s a far more somber and scarce occasion. Half the bench is empty and it just doesn’t feel right. It’s their new reality. This is what war does. But on Sunday at the church service, something very special happens, and it makes Charlie’s shattered heart full once more.

Because of the time period of its release, I feel like Shenandoah functions better on this more universal gradient as a story about a father, one who just happens to live during the Civil War.

It’s hard not to watch the film and also place it up against the current events of the Vietnam conflict which was still in its relative infancy, at least based on U.S. involvement.

James Stewart was of course known to be a more conservative man and even flew a bombing mission over Vietnam on February 20, 1966. By the end of his military career, he would end with the rank of brigadier general. It’s necessary to come to grips with the ambiguity of this.

Because whether he recognized the implications or not — and he was hardly a dummy — Shenandoah does become a kind of antiwar statement running parallel to the Vietnam conflict. And this is while it still remains firmly entrenched in the kind of old Hollywood depicted in family westerns like The Rifleman or The Big Valley.

It’s not like you’re going to see hippie haircuts, acid trips, or postmodernist revisionism. It’s resolutely clean-cut. Within this framework, the pacifist inclinations are still clear in the tradition of William Wyler’s Friendly Persuasion (1956).

I was ruminating over this idea that while Stewart was an obvious patriot who was an avid pilot and served with honor during World War II, I’m not sure if he could be considered a war hawk. They aren’t quite the same thing.

Of course, you could have an entire sidebar about how the Vietnamese in the 20th century or the Blacks during the Civil War weren’t given the same considerations and dignity as whites, but I’m an optimist.

When I watch this film it makes me want to fight for family, something far greater than any political or personal agenda. It’s something worth living and even dying for. Of course, when you bring it into modernity and it butts up against current events, the issue becomes a lot more tangible and equally murky. It’s easier when you can take ideas in a theoretical context and they aren’t staring you right in the face.

3.5/5 Stars