In his opening introduction, Kumail (comedian Kumail Nanjiani playing a cinematic version of himself) explains what it was like to grow up in Pakistan with cricket and praying and arranged marriages. All those fun Pakistani traditions. There’s a bit of a matter-of-fact flippancy to how he recounts it all. Truthfully, it’s in stark contrast to much of what we’re used to. As he so rightfully points out, it also meant they got episodes of Knight Rider a lot later than everyone else. That’s before his parents made the decision to move to the States with their two sons.

In his opening introduction, Kumail (comedian Kumail Nanjiani playing a cinematic version of himself) explains what it was like to grow up in Pakistan with cricket and praying and arranged marriages. All those fun Pakistani traditions. There’s a bit of a matter-of-fact flippancy to how he recounts it all. Truthfully, it’s in stark contrast to much of what we’re used to. As he so rightfully points out, it also meant they got episodes of Knight Rider a lot later than everyone else. That’s before his parents made the decision to move to the States with their two sons.

America has always been a melting pot since the day of Alexis De Tocqueville and that’s part of what this film celebrates while never completely denigrating Kumail’s Pakistani roots. It so refreshingly provides a story told from a different point of view — one that we have not seen all that often — which is all illustrated so exquisitely in the opening moments.

But The Big Sick is also resonant in part because of the conflict of cultures that dwells at its core. A differing perspective usually causes chafing and it’s no different in this case. Still, at first, it must start out as a love story and it is or at least it evolves into one. This particular romance feels invariably relevant to the current world we find ourselves in. It’s a picture informed by a 21st-century worldview.

Kumail is making a go of it as a stand-up comedian in the Windy City and he makes ends meet with a bit of Uber driving. He meets a girl named Emily (Zoey Kazan) at his comedy club, a local grad student with aspirations to be a therapist. They go on a date and wouldn’t you know it, they sleep together. That is the culture after all as much as Uber, ethnic diversity, profanity, and irreligiousness.

Perhaps it’s more precisely put by Kumail who so candidly admits he hasn’t prayed for years because he does not know what he believes. That is the world that this movie occurs in, our world right here and now. They have their rounds of playful patter and time spent together watching Kumail’s favorite horror movies (he proudly has a poster of Shaun of the Dead up on his wall like any unabashed nerd). Still, they are equally noncommittal in how they never want to get too serious about relationships.

It makes sense that romances are about relationship but often those very things are also so closely tied to family. Both sets of parents play a significant role in the picture and certainly, none of them are perfect — exhibiting a wide range of idiosyncrasies — and yet the key seems to be that they are more than a pair of punch lines. It’s those very relationships too that seem to add even a greater depth and heighten the stakes. Because parental commitment more often than not is for the long haul even when their kids’ relationships don’t seem to be.

In case the title didn’t tip you off already, I’ll save you the trouble and let you know that Emily winds up sick in the hospitable. The people by her side are her mom (Holly Hunter), her dad (Ray Romano), and Kumail who feels bad even as their relationship was all but finished.

As we get to know them as people though, it really feels as if we are getting a better understanding of Emily and the same goes for Kumail. In the same way that Kumail feared telling his family that he was dating a white girl, we see another culture clash in her parent’s who fell in love years ago despite coming from two very different backgrounds, one a stiff New Yorker the other a southern belle in a football-loving family.

Kumail begins to gain a certain modicum of courage to stand up to his own parents, in particular, a mother who is always trying to set him up with a nice Pakistani girl like she did with his older brother. He’s weathered a long list of resumes and “drop-bys” by the most eligible Pakistani ladies. We sense the need for personal integrity. He needs to learn how to exercise it not only in dealing with Emily but his parents as well.

You can still be an American and embrace other cultures and that’s one of the keys to this story because navigating that can be utterly trying. Our differences far from encumbering us should bless us with life more abundant and humanity still proves that love can be a universal language that crosses many divides, cultural or otherwise.

Furthermore, could it be that this film too succumbs to that character trope formerly in vogue as the manic pixie dream girl? It’s a stretch since this is based on real events but it falls apart further still as we watch the film progress to its full conclusion. Because if you remember this fantasy character is meant to bring something out of the male character and cause a change in them. That does happen to Kumail to an extent.

The crucial development for the sake of Zoe Kazan’s character is the fact that she is allowed more growth than simply being the cause of Kumail’s growth. Thankfully she is more than a mere plot device. She is given the dignity of an actual human being meaning that she’s able to acknowledge that maybe she hasn’t changed as much as him — she’s not ready to just go back to the way things were before — and that’s okay because that feels authentic.

That’s not to say there can’t be a happy ending but as many of the greatest modern romantic comedies have managed this one leans into ambiguity and makes that a strength far more than a weakness. Kumail has gone onto to pursue his stand-up career. Emily no doubt continues her aspirations to become a therapist. Still, there’s such a thing as a fairy tale and this might be a good time to point out again that this is semi-autobiographical. Real life fairytale romances are possible. They just usually happen to be a lot messier than we’ve read about in books. A lot like this story.

3.5/5 Stars

Update: On September 16th, 2017 a man named Nabeel Qureshi passed away. And I bring up his extraordinary life because it was difficult for me not to see the parallels to this film.

Like Kumail, Nabeel was Pakistani-American. Like Kumail, Nabeel also faced the challenges of going against the wishes of his parents when it came to core aspects of his life. Like Kumail, Nabeel and his wife faced the malevolent onslaught of sickness. But in Nabeel’s case, the sickness struck him and he did not recover.

It sounds like a very sad tragedy and it is bittersweet but I reference it because Nabeel was a man who had tremendous joy and hope and he left such a lasting impact on his fellow man. It is a life worth sharing about. I enjoyed the Big Sick but even in the last few months and weeks, I have been inspired by Nabeel Qureshi’s life even more.

In his noted Crisis of Confidence Speech, incumbent president Jimmy Carter urged America that they were at a turning point in history: The path that leads to fragmentation and self-interest, down that road lies a mistaken idea of freedom. It is a certain route to failure.

In his noted Crisis of Confidence Speech, incumbent president Jimmy Carter urged America that they were at a turning point in history: The path that leads to fragmentation and self-interest, down that road lies a mistaken idea of freedom. It is a certain route to failure. Are you leaving room for Jesus?~Amanda

Are you leaving room for Jesus?~Amanda “Nicole, you’re sleeping…”

“Nicole, you’re sleeping…” “Things are only as meaningful as the meaning that we allow them to have.” ~ Beverly

“Things are only as meaningful as the meaning that we allow them to have.” ~ Beverly

Where to start with Liberal Arts? It’s one of those deep blue funk movies. Zach Braff tackled this issue in Garden State, and Josh Radnor does a similar thing here. Because the reality is that we live in a generation of early onset midlife crises. In the opening moments, 35-year-old Jesse Fisher (Radnor) has nearly every article of clothing he has aside from the shirt off his back stolen from a local laundromat when his back is turned. We can easily surmise that this single event epitomizes his life right now, and this is hammered home rather obviously when his unnamed girlfriend clears her belongings out of his flat. There’s no better symbol of isolation and alienation than a break-up.

Where to start with Liberal Arts? It’s one of those deep blue funk movies. Zach Braff tackled this issue in Garden State, and Josh Radnor does a similar thing here. Because the reality is that we live in a generation of early onset midlife crises. In the opening moments, 35-year-old Jesse Fisher (Radnor) has nearly every article of clothing he has aside from the shirt off his back stolen from a local laundromat when his back is turned. We can easily surmise that this single event epitomizes his life right now, and this is hammered home rather obviously when his unnamed girlfriend clears her belongings out of his flat. There’s no better symbol of isolation and alienation than a break-up. It’s crucial to note that at this juncture nothing substantive builds between these two acquaintances romantically, but they do foster an immense connection. While Jesse is taken by Zibby’s personality, she, in turn, is discontent with a contemporary culture where no one dates–everybody’s casual about relationships. She feels unequivocally millennial and yet she readily admits these areas of old-fashionedness.

It’s crucial to note that at this juncture nothing substantive builds between these two acquaintances romantically, but they do foster an immense connection. While Jesse is taken by Zibby’s personality, she, in turn, is discontent with a contemporary culture where no one dates–everybody’s casual about relationships. She feels unequivocally millennial and yet she readily admits these areas of old-fashionedness. Coming out of a psychology background I was familiar with Stanley Milgram’s famous social experiment back in high school during Intro to Psych. Even back then it was a striking conclusion on conformity and just how far people will go. It was also ruthlessly contrived and even more methodically executed. Inspiration came from Milgram’s own background working with psychologist Solomon Asch, as well as his own Jewish ancestry, nights watching Candid Camera, and a fascination in the Adolf Eichmann trial.

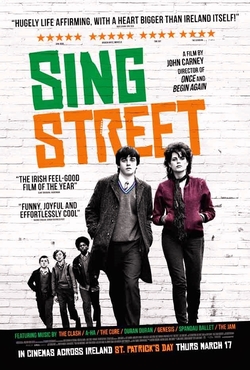

Coming out of a psychology background I was familiar with Stanley Milgram’s famous social experiment back in high school during Intro to Psych. Even back then it was a striking conclusion on conformity and just how far people will go. It was also ruthlessly contrived and even more methodically executed. Inspiration came from Milgram’s own background working with psychologist Solomon Asch, as well as his own Jewish ancestry, nights watching Candid Camera, and a fascination in the Adolf Eichmann trial. A famed philosopher of the MTV age once sang “video killed the radio star,” and John Carney’s Sing Street is a tribute to that unequivocal truth. Certainly, it’s what some might call a return to form for the director, landing closer to his previous work in Once, and staging the way for some wonderfully organic musical numbers set against the backdrop of Dublin circa 1985. In this respect, it’s another highly personal entry, and Carney does well to grab hold of the coming-of-age narrative.

A famed philosopher of the MTV age once sang “video killed the radio star,” and John Carney’s Sing Street is a tribute to that unequivocal truth. Certainly, it’s what some might call a return to form for the director, landing closer to his previous work in Once, and staging the way for some wonderfully organic musical numbers set against the backdrop of Dublin circa 1985. In this respect, it’s another highly personal entry, and Carney does well to grab hold of the coming-of-age narrative.