The Old Dark House (1932)

The Old Dark House has a disarming levity that broadsided me at first. James Whale, the man who famously gave us Frankenstein, has all of his notable features with the tinges of horror on hand for another ghastly delight, and then he goes and pokes fun at the whole setup. Raymond Massey is instantly pegged as a slightly stuffy husband. His wife, dazzling Gloria Stuart, a young ingenue has signed up for more than she bargained for with the outrageous downpour dousing them in the dead of night.

Then, there’s old reliable Melvyn Douglas playing his quintessential character type, always good for a wisecrack, with his feet kicked up, and his pipe tucked in his mouth as they proceed to get hopelessly lost. And of course, he can’t help but whistle a few fractured bars of “Singing in the Rain” when their waterlogged buggy has no recourse but become semi-amphibious.

Oftentimes bathos is used as a kind of criticism — this idea of anticlimax or a break of the mood — because it’s too jokey and therefore undermines all the groundwork put down before it. However, Whale seems to be doing something different.

At any rate, it’s not an out-and-out drama and so while somehow deconstructing his tropes and suggesting to his audience he knows precisely what he’s doing, we reap the benefit of the humor and the chills in ample measure. This is the underlying success of the film in a nutshell. It carries off both and becomes invariably more intriguing in the process.

Because The Old Dark House fits seamlessly into the tradition of Cat and the Canary, Hold That Ghost, House on Haunted Hill et al. A dark and stormy night is a genre given, but the abode itself must bring with it the unnerving idiosyncrasies to make the audience ill at ease. Rest assured. It does.

The proprietors include a white-haired gentleman trembling with timidity and his eternally deaf and priggish sister who condemns all blasphemers en masse. Their valet (Boris Karloff) might as well be a grunting prototype for the wolf man. All of this doesn’t quite suggest a warm and amicable atmosphere. It screams something else. But that’s just the beginning of the festivities…

If I’m to be terribly honest, it seems like an utter waste of Karloff’s talents, especially because I was barely aware he was playing the part. He gets partially overshadowed by the more verbal characters. Charles Laughton, for one, comes tottering through the front door soaked through as gregarious Sir William accompanied by his playful and rather giddy companion (Lilian Bond). Her lithe spirit mirrors Douglas, and they gel nicely. The night quickly turns them into an item. In fact, all the guests hang together.

One could wager it comes out of necessity. It’s a ghoulish space filled with funhouse angles and other parlor tricks. Locked upstairs is a decrepit patriarch and behind another closed door is crazy Saul, who makes a cameo appearance spouting the story of King Saul and David. You know the one, where malevolence came over Saul and he proceeded to spear the other man to death.

He finds a knife and brandishes it with a kind of giddy insanity we don’t know how to respond to. He could do anything. Douglas, the picture of casual confidence and charm for most of the picture, finds his own veneer unseated filling in for David. It’s these kinds of digressions that we never expected, and somehow they make the picture by leaving the audience totally nonplussed.

By the time The Old Dark House is wrapped up, it feels like the gold standard of this brand of haunted house movie because it’s just as much about being a mood piece — finding humor in these outlandish scenarios — and Whale does all of the above with assured aplomb.

4/5 Stars

The Invisible Man (1933)

I always thought about The Invisible Man as a scientific marvel, but now I understand how he’s firmly planted in the realm of horror with added superhuman abilities. There’s something that feels somehow modern about Claude Rains’ portrayal of the eponymous character. It’s almost as if he’s the precursor to some enigmatic alien creature from Star Wars.

He’s unique and out of step with this more traditional setting of a bar and lowly establishment as local folks chew the fat and the incomparable Una O’Connor runs the place. One feels quintessentially British, albeit through the prism of the Hollywood dream factory. Rains is totally a movie machination born of smoke, mirrors, and special effects.

But it’s also as if this camouflage provided Rains the means to give one of his most ballistic and volatile performances. It’s not that he couldn’t play, wry, sly, or even bad-tempered, but his typical onscreen disposition was one of regality. He commands the room but in a very different way.

He’s seething one moment and then hysterical the next. The local constable rightly asserts, “He’s invisible. He gets those clothes off and we’ll never catch him for a thousand years!” It makes the stakes obvious. Soon thereafter the maniacal doctor commences a reign of terror making good on his threats by committing murders and diverting trains off their rails. He makes it clear he has the power to make the world grovel at his feet.

If it’s not obvious already, he’s taken on the mantle of a violent “Superman” cut out of the cloth of Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov. What’s worse, there seems to be no one capable of stopping him.

What’s most fascinating is how the film builds the legitimacy of the Invisible Man. It’s not merely a sitcom-like trope where the invisible are given the freedom to pull practical jokes or take on a Groundhog Day-type disregard of worldly conventions. This is part of it, yes, until it becomes something more.

It turns into a story of fear and broader social implications broadcasted over the news and through every small town by word of mouth. He’s continually left unchecked and the drug he’s taking pumps him full of delusions of grandeur. It’s a drug and addiction of a different sort. Not even the affection of his former girlfriend (Gloria Stuart) can change his mind. He’s too far gone.

The special effects and the choreography get better and better as a crowd of bobbies forms a human dragnet to converge on him in the dead of night. He skips away with a policeman’s trousers sowing chaos and discord wherever he goes. But before anyone gets the idea The Invisible Man is a mere lark, we’re quickly shocked back to reality.

It has a jagged edge of vindictiveness which the production codes would make sure soon enough would never see the light of day (at least for a good many years). For now, it feels like a chilling, compact drama chock full of ideas, invention, and not a wasted minute of running time. It’s also without a doubt Rains’ finest entrance in a movie: It happens in the final frame.

4.5/5 Stars

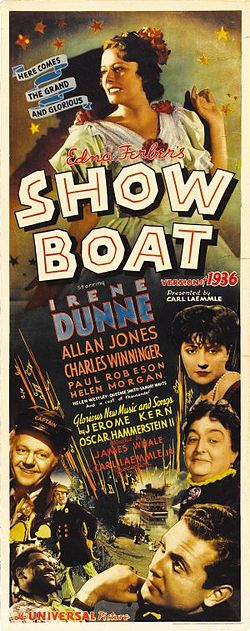

Most of what I know about riverboats can be gleaned from Mark Twain, Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, and that ever beloved Snoopy incarnation The World Famous River Boat Gambler. The 1936 musical Show Boat falls into that very same rich tradition but some clarification is in order.

Most of what I know about riverboats can be gleaned from Mark Twain, Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, and that ever beloved Snoopy incarnation The World Famous River Boat Gambler. The 1936 musical Show Boat falls into that very same rich tradition but some clarification is in order.