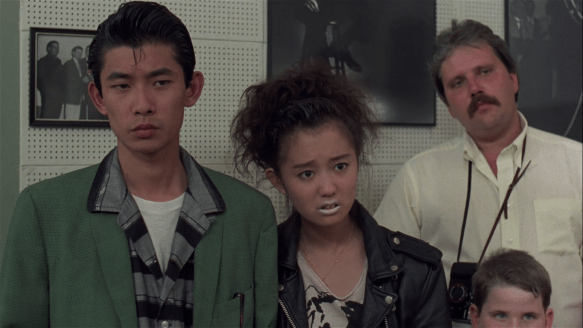

I hold an immediate affinity for the images at the core of Mystery Train: A Japanese couple (Youki Kudo and Masatoshi Nagase) riding a train. This is the ’80s so they’ve got a walkman with an audiocassette tape, and it’s blaring Elvis! It becomes apparent they are making a pilgrimage to Graceland so famously immortalized by Paul Simon. The song “Mystery Train” becomes an apropos and uncanny way to enter the story while paying homage to the King.

Jim Jarmusch always strikes me as such an open-minded and curious filmmaker. Modern society speaks in terms of diversity and inclusion, but the beauty of watching a Jarmusch picture, it’s the fact he’s not looking for these things in order to meet some quota. He seems generally interested by the stories and perspectives a whole host of characters can provide him, and his films benefit greatly from this enduring proclivity.

Regardless of where the funding came from, who else would consider making a film about two Japanese youth in search of Elvis Presley in the 1980s? They spend the first several minutes speaking a language that the primary audience probably does not understand. They likewise are bewildered by a upbeat yet motormouthed docent at Sun Records. Still, somehow shared passions for Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison et al., draw them together in inextricable ways.

There’s something perfectly fated about the whole thing with Screaming Jay Hawkins as a rather flamboyant hotel clerk aided by a youthful bellhop (Cinque Lee). I don’t know how to describe it but Hawkins has a command or a sway over the picture rather like Wolfman Jack in American Graffiti. His presence is felt and becomes so indelible in accentuating an aura. He comes to represent a certain era and a place in human form.

Jarmusch’s characters of choice often feel like sojourners, strangers in a strange land and Memphis is such a place. It is a film that features degradation — cracked pavements, garish neon lights, and portions of the world that are not perfectly manicured. What a concept. It’s almost like Jarmusch is giving us the real world albeit composed through his own cinematic lens. It’s no coincidence it has this kind of baked-in glow of Paris, Texas another film of geographical Americana captured so exquisitely by Robby Muller

It’s only a personal observation but my level enjoyment slightly decreased with each descending story. As someone who journeyed in Japan and went to one of the greatest concerts of my life in Yokohama, I feel this kind of kinship with these Japanese youths in their pilgrimage to Elvis and Carl Perkins. Also, on another level, this is a point of view we just don’t often see in movies of the 1980s or even today. Jarmusch is not using them as some kind of stereotypical punchline. He’s genuinely interested in their story and allowing it to play out in front of us.

Then, there’s Nicoletta Braschi in part two. She’s told a ghost story by a dubious stranger and gives him a tip to be left alone. She too seeks asylum for the night at the same hotel and gains a chatty roommate (Elizabeth Bracco) who is linked to our final vignette.

This last interlude with Steve Buscemi feels like it exists in the time capsule moment of a certain era where Tarrantino, the Coens, and others were making these stylized, often grotesque comedies. Elvis (Joe Strummer) gained his nickname inexplicably, but he’s also started to become unhinged because his girlfriend went up and left him. The cocktail of booze and firearms make his buddies Charlie (Buscemi) and Will Robinson (Rick Aviles) uneasy. Although it feels more like an absurd episode of The Twilight Zone than Lost in Space.

Regardless of my own preferences, Jarmusch still gives his world a sense of purposefulness. Again, it’s this serendipitous quality reminiscent of Jacques Demy’s fated films where lives cross paths and intersect in deeply poignant ways.

There’s something somehow elegant about the structure. It’s certainly premeditated and Jarmusch purportedly was inspired by classical literary styles in constructing his triptych, but it’s also a genuine pleasure to watch it unfurl.

The movie revolves on the axis of a few shared moments and places: A hotel, a radio DJ (Tom Waits) playing “Blue Moon,” and a gunshot. But it’s not like they’re all building to some kind of collective crescendo; it’s more so just a passing indication of how lives, whether they mean to be or not, are often interrelated.

Characters orbit each other and interact in these preordained ways that reflect the mind of the maker, in this case, Jarmusch. There’s something oddly compelling and comic about it, but there’s simultaneously a sense of comfort. We have order and a kind of narrative symmetry leading back out from whence we came.

Jarmusch is calling on the poetry of the ages and so in a movie that seems to have a free and laissez-faire attitude, there’s still a very clear order behind it, three distinct threads end-to-end and yet still interwoven into a tapestry that we can appreciate. Mystery Train represents the best in cinematic storytelling — with purposeful composition and aesthetics — but also a sense of aura and inscrutability.

It’s funny and yet when it’s over there’s also satisfaction and a hint of wistfulness. I wish there were more of its ilk today. The movie that’s come the closest is Paterson — another modern jewel from Jim Jarmusch. I see that film in a new light as a much older, wiser, and more forthcoming Masatoshi Nagase sits down on a bench with Adam Driver.

Again, it is a story about the human journey, how we are all travelers in some sense, and what a beautiful thing it is to relish the road because it can lead us to so many beguiling places if we take the time.

4/5 Stars