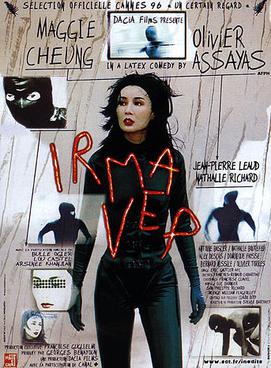

Our entry point into Irma Vep as an English-speaking audience is Maggie Leung, and although this is a French production from Olivier Assayas, it’s almost as if he’s provided us an avatar. The cinematic Maggie in the film becomes our window into the world created around her.

Our entry point into Irma Vep as an English-speaking audience is Maggie Leung, and although this is a French production from Olivier Assayas, it’s almost as if he’s provided us an avatar. The cinematic Maggie in the film becomes our window into the world created around her.

Although the film is from a bygone generation, it’s modern in the way of filmmakers like Jim Jarmusch who seem curious, open-minded, and intent on fleshing out stories that spill out across different cultures.

Cheung is congenial throughout, and it’s no wonder she has become a luminary figure in world cinema. In The Mood for Love will immortalize her and Tony Leung for posterity’s sake. But in Irma Vep she feels so much like a contemporary person we can comprehend and understand intuitively. She’s an actress yes, but there’s something down-to-earth and so personable about her.

In a film of continual strife, she seems to be this enduring ray of optimism and warmth for everyone around her. Although her being an outsider carries with it a certain naivete, she’s also excited to work and do something she finds to be enjoyable.

Even as the local crew gripe with one another, most everyone is amenable to her, speaking English and doing their best to make her feel at home regardless of what they think about her casting. One of her primary acquaintances is Zoe (Nathalie Richard), a fiery costumer who helps her navigate the chaos by transporting her around the city and welcoming Maggie into their nighttime commune of technicians. She also harbors a little crush on the film star.

It’s a wonderful confluence of worlds being smashed together and even with its humble handheld camera sensibilities, we recognize the international scope of the production. This is what French cinema, what European cinema, can afford us if we burst through our myopic Hollywood blockbuster lens.

It has a brash energy to it that fits in with the up-and-coming directors of the ’80s and ’90s. Some had been to film school, others knew about the French New Wave, and out of it was birthed a generation of films full of grit, life, and personal expression. Assayas might be a few years older, but he looks intent to say something very particular.

Part of me wonders if this period of film is dead as our technology gets more advanced, and it becomes cheaper to shoot better quality footage that more easily hides budgetary restraints. Obviously low budgets are still a part and parcel of making it in the industry, but with filmmakers like Richard Linklater or even Assayas here, there’s a certain simplicity to their work where their personal vision in some ways outpaces or totally transcends the limited resources at their disposal.

I was thinking how much ’90s energy the film embodies when it harnesses Sonic Youth’s “Tunic” doing a survey of Maggie’s hotel room when she returns home late at night. We are constantly bumping up against the self-reflexive nature of the movie with Cheung playing a film version of herself. She is the Hong Kong action star who Rene Vidal (Jean-Pierre Leaud) believes is the only enigmatic beauty in the world who can play the modern incarnation of his heroine: Irma Vep.

When she’s not slinking around her scenes or getting fitted in a latex catsuit, she’s being interviewed by a French journalist about John Woo action cinema and French stars like Alain Delon and Catherine Deneuve — real constellations of film history.

It’s almost second nature to trace the lineage from Day for Night to Irma Vep even as it’s indebted to the silents: Les Vampires in particular. Jean-Pierre Leaud’s eccentric mad scientist behind the camera spouts off his director-speak between sips of his 2-liter Coca-Cola. It’s his mercurial nature guiding the whole production and thus sending it toward a tailspin of discombobulation.

Day for Night is often about this illusion of cinema where you don’t know where the movie ends and reality begins. Irma Vep has some of that — Cheung becoming a nighttime cat burglar quickly comes to mind — but its greatest debt to the earliest project is portraying the behind-the-scenes mayhem of a film production.

So much goes wrong; there’s chaos and personal troubles. Watching films such as these, it’s a wonder movies get made at all. If I’m sometimes uncompassionate toward Hollywood, then Irma Vep gives Assayas license to bash the French film industry whether it be navel-gazing directors or unprofessional crews. However, for all the criticisms he lobs its way, he’s still a part of it, and revels in its traditions because it still manages to be deep and rich. One must appreciate how both can be true at the same time. So it is with Irma Vep.

Leaud is the first of the main players to evaporate into the silence. Then Maggie drives off in a taxi, and we never see her again in the flesh. The film itself descends into a hypnotic montage of shapes and images and rhythms, with eyes scraped out and a kind of gutted soundscape.

What it is exactly? You tell me. All I know is I felt something. Irma Vep is a reminder that the moving image has unadulterated power, and it’s what’s made the movies such a mesmerizing opiate for over a century. We’re still finding new layers and new forms of self-expression in them all these years later. I hope this does not die out any time soon.

4/5 Stars