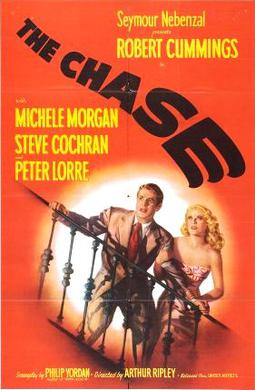

The Chase opens as a wonderful contrivance of noir done up in a couple of successive visuals. A bedraggled man (Robert Cummings) stares through a shop window at a griddle laden with fresh bacon and hot cakes. He leans in so his hat brim mashes up against the glass, and proceeds to cinch up his belt. He doesn’t have any dough.

Then, he looks down right at that precise moment and notices a wallet at his feet stacked with cash. Any person in the real world would have seen it immediately, but it’s set up perfectly for the camera. He proceeds to treat himself to breakfast and a cigar, and after he has a full belly, he decides to pay a visit to the address inside the wallet.

You get a sense of the milieu with a mention of a standoffish Peter Lorre staring through a peephole and questioning what the stranger wants. Our hero is unwittingly cryptic, saying he wants to see one Eddie Roman — he has something to give him…

It could be a belly full of lead or something more innocuous, and, of course, it’s the latter. They give him the once over and reluctantly let him in. The room’s stacked high with statues and ornate antiquities; somehow, they make the interiors feel not just capacious but hollow.

Who lies down the corridors is anyone’s guess because this isn’t where ordinary folks dwell, only cinematic creations. Sure enough, the ex-Navy man Chuck Scott has just happened to fall in with a psychotic lunatic (Steve Cochran). We’re introduced to his temperament when he gives his manicurist a slap for screwing up and sends her simpering out the front door.

Still, he’s impressed by Chuck: An honest guy shows up on his doorstep, and he even tells him he treated himself to breakfast for a dollar and a half (those were the days!). For being such a standout guy, he repays him with a gig as his chauffeur. When you’re destitute, you don’t bite the hand that feeds you.

There’s an uneasy tension in everything Cochran and Lorre, his right-hand man, have their hands in. The controlling Eddie is married to a young lady (Michèle Morgan) named Lorna; he’s hardly allowed her out of the house in 3 years. It says so much about their relationship.

The sadistic slant of the movie becomes increasingly apparent as they stick a different dinner guest in the wine seller to be ripped apart by Eddie’s prized pooch. He has something they want for their business dealings, and any semblance of hospitality burns off as his bubbly conversationalism quickly turns into despair.

For a time, The Chase becomes a kind of contained chamber piece drama. It’s not obvious if it will break out and be something more as Chuck forms an uneasy existence between the backseat driving of his new boss and the despondency of Lorna, who stares out at the crashing waves of the ocean, all but bent on presaging Kim Novak in Vertigo by jumping in and ending it all.

Lorna and her newfound advocate book two tickets to Havana and are prepared to skip out together. Even these scenes evoke a foreboding mood more than anything more concrete because there’s only a vague sense of plot or purpose. From here, it builds into this debilitating sense of obscured conspiracy in the bowels of Havana.

There are obdurate carriage drivers, slinking foreigners, and cloak-and-dagger antics that find his woman harmed and Chuck fleeing from the authorities. The surreal tones of the story just continue to proliferate with novel characters and new environs materializing rather than moving systematically from one scene to the next.

This inherent sense of surreal atmosphere might place the picture ahead of its time, with a select few films of the era. However, it comes off as rather stultifying after auspicious beginnings because it doesn’t accomplish what many of the great Classical Hollywood films managed by telling compelling three-act stories with a sense of economy.

The underlying perplexing tension set against a dreamscape, siphoned from Cornell Woolrich’s source material, is not enough for The Chase to fully pay off on the goods. It feels more like an intriguing experiment than a successful crime drama.

3/5 Stars

Here is another entry in our ongoing series of Classic Hollywood Stars who are still with us.

Here is another entry in our ongoing series of Classic Hollywood Stars who are still with us.