It’s not a groundbreaking observation, but the French seem predisposed to have a less dismissive posture toward genre fare. I’ve written ad nauseam about how Jerry Lewis has lasting appeal overseas (befuddingly I know).

It’s not a groundbreaking observation, but the French seem predisposed to have a less dismissive posture toward genre fare. I’ve written ad nauseam about how Jerry Lewis has lasting appeal overseas (befuddingly I know).

In the ’50s and ’60s, The Cahiers du Cinema gang did their best to champion Howard Hawks, Nicholas Ray, and Hitchcock among others — all capably genre-orientated — “smugglers” as Martin Scorsese called them. Because these were filmmakers who worked within the tropes and constraints of genre to share their personal vision with an audience through popular entertainment.

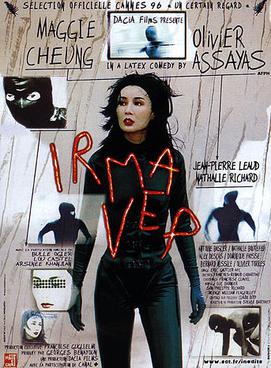

Here, jumping forward into the 21st century, we have a director in Oliver Assayas intent on casting the girl of werewolf acclaim — Kristen Stewart — in his movies. Many of us have a myopic view and would never consider this, but again, something about our colleagues across the sea, they can see inspiration where we cannot.

First, Stewart showed up in Clouds of Sils Maria with Juliette Binoche and then as Personal Shopper becoming a focal point unto herself. Personal Shopper is a modern-day ghost story.

I’m not particularly fond of the genre of apparitions and haunted houses so I’m predisposed not to appreciate the movie. However, it’s self-evident Assayas is not content in making a conventional ghost story. He wants to use it for alternative purposes — to consider human themes — and his ready muse is Kristen Stewart.

If you take a cursory survey of Personal Shopper, it feels like disparate worlds melding ideas of 19th century spiritualists and theosophy with the modern landscapes of high-end fashion and personal assistant-driven celebrity.

Because Maureen (Stewart) is a personal shopper and general grunt for a narcissistic fashion model even as she spends her off hours looking to make contact with a presence she feels. She lost her twin brother Lewis; he left behind a wife in Paris, and Maureen is driven to search for signs from the deceased. In a deserted home, she meets a mercurial spirit later recounting the event matter-of-factly to her sister-in-law (She vomited this ectoplasm and left…).

It’s only subsequently that we realize how the personality she slaves for and the spirit of her brother she searches for feel eerily similar. They exist on the outskirts and hinterlands of her life mostly disembodied from their physical selves by technology or the great beyond. And practically this has deep implications.

There are minor special effects throughout the film, but it relies on the performative aspect of Stewart and her bearing herself in front of the camera. She mostly does a single as she drifts through the film, rides her motorbike through the city, and frequents spaces with a moody despondency we can all appreciate.

She begins getting mysterious text messages; it feels like she’s being catfished by a ghost — or is the correct term ghosted? I don’t have the vocabulary to describe it, but it happens and never shatters what we deem to be reality. Assayas seems fine even pleased to have his film come off as a blend of horror and psychological thriller with the aforementioned specters and a stalker playing mind games with Stewart.

Later, there’s a conversation Maureen has with her sister-in-law’s new boyfriend (the trusty Anders Danielsen Lie), setting up arguably the most crucial scene in the movie. Because eventually he leaves and we see a glimmer of something — a figure, there’s a glass — and then a smash! This triggers her attention and she goes to investigate and clean up the debris. It’s the most overt sign in the movie thus far. Only we see it for what it is. The veil is pulled back for us momentarily, and then it’s gone.

Eventually, she decides to leave Paris behind and visit her boyfriend in Oman — another disembodied presence we never see again. Instead, she arrives at their mountain getaway and has a different encounter…It’s like a tantalizing breadcrumb, but any of us who live in a mortal world predicated on faith knows there are few easy answers. Any tap might be the supernatural speaking to us or the rustle of the wind blowing wherever it pleases.

While I appreciate the yeoman’s work Stewart does with her listlessness and also the distinctive take on the contemporary ghost story, Personal Shopper does not satiate me. I appreciate the ambiguity and the open-mindedness. Still, it’s unclear if Assayas’s means for all the pieces to fit together or if he’s only giving vague shades and strands of impressions and allowing us to fit them together as we so desire — hoping we will attribute it to some deeper meaning.

It’s possible he’s compelling us to make a judgment of faith or otherwise suggesting there is no definitive truth in the story a la Antonioni. We’ll never know. It’s a film that deserves further consideration. This time around my gut wasn’t entirely convinced. Because it doesn’t quite pass the litmus test of genre entertainment even if it does pass the intellectual grade.

3/5 Stars