From the haunting opening notes of a lullaby to the otherworldly aerial shot floating over New York, Rosemary’s Baby is undeniably a stunning Hollywood debut for Roman Polanski.

From the haunting opening notes of a lullaby to the otherworldly aerial shot floating over New York, Rosemary’s Baby is undeniably a stunning Hollywood debut for Roman Polanski.

What follows is a tale weighed down by impending doom and paranoia. But although the tone is very much suited for Polanski, it’s perhaps even more surprising how faithful his adaptation is to the original source material. Most of the dialogue if not all of it is pulled from the pages of Ira Levin’s work and the Polish auteur even went so far as getting the wallpaper and interiors as close to the novel’s imagery as he could. But that hardly illuminates us to why the film is so beguiling–at least not completely.

In an effort to try and describe the look of the film, the best thing that I can come up with is inscrutably surreal. Some of it is undoubtedly due to the lighting. Partially it’s how the camera moves fluidly through the cinematic space which is mostly comprised of interiors. But nevertheless, it’s absolutely mesmerizing to look at and it pulls you in like the wreckage of a car crash. As much as you don’t want to, your eyes remain transfixed.

Mia Farrow, with her figure gaunt and her hair short, becomes the perfect embodiment of this young wife. The progression she goes through is important. Because she starts out young, bright-eyed and cute. Still, as time progresses she evolves into her iconic image, shadows under her eyes, ruddy and covered in beads of sweat. Her state is no better signified than the moments when she walks through oncoming traffic in a complete psychological daze.

John Cassavetes brings his brand of comical wryness to the role of the husband and struggling actor. But face value gives way to more sinister underpinnings. Old pros like Ruth Gordon, Sidney Blackmer, and Ralph Bellamy are given critical parts to play as an overly hospitable old crone and her husband and the aged doctor who are all privy to this deep-seated conspiracy.

You’ll find out soon enough what that means if you watch the film. However, for me what kept coming back to me is that this is, in essence, a subversion of the Christ child narrative with a new “Mother Mary” figure. And hidden behind this psychological horror show is something, oddly enough, darkly comic. It’s summed up by the scene in the doctor’s office waiting room where Rosemary begins to leaf through Time Magazine. The headline reads bluntly, “Is God Dead?” As a relapsed Catholic surrounded by people who scoff at religion, the world is seemingly devoid of such things. Even the film itself features more profane moments, greater sensuality, and darker themes than any film of the early 60s. Thus, that magazine headline is not too far from the truth

It’s a question that many would have undoubtedly answered in the affirmative in 1968 too, a year fraught with rebellion, unrest, assassinations, and conflict. Polanski himself would even lose his beloved wife Sharon Tate at the hands of the Mansion family. Mia Farrow was served divorce papers by Frank Sinatra on set. It surely was a dark time and yet while Rosemary’s Baby is disillusioning, there’s also an absurdity running through it.

However, the bottom line is that it maintains its frightening aspects because so much is left ambiguous. We don’t see the baby. We never fully understand what’s afoot. And we don’t even know what will happen to Rosemary in the end. What choice will she make? What path will she choose? Is this all a cruel nightmare or will she wake up? Can anyone rescue her from her torment? There are no clear-cut conclusions only further and further digressions to be made. There’s something fascinatingly disturbing about that. It ceases to grow old.

4.5/5 Stars

Inspired directors oftentimes do not make themselves known in grandiose flourishes but in the smallest of touches, and in his debut, Polish newcomer Roman Polanski does something interesting with the opening of Knife in the Water. Perhaps it’s not that unusual, but it’s also hard to remember the last film where the camera was on the outside of a driving car, looking in. We see shadows of faces overlaid with credits and then finally the faces are revealed only to be shrouded by the reflections of overhanging trees glancing off the windshield.

Inspired directors oftentimes do not make themselves known in grandiose flourishes but in the smallest of touches, and in his debut, Polish newcomer Roman Polanski does something interesting with the opening of Knife in the Water. Perhaps it’s not that unusual, but it’s also hard to remember the last film where the camera was on the outside of a driving car, looking in. We see shadows of faces overlaid with credits and then finally the faces are revealed only to be shrouded by the reflections of overhanging trees glancing off the windshield. Thus, it becomes an exercise of technical skill, much like Hitchcock in Lifeboat or any other film that limits itself to a single plane of existence. Polanski’s framing of his shots with one figure right on the edge of the frame and others arranged behind is invariably interesting. Because although space is limited, it challenges him to think outside the box, and he gives us some beautiful overhead images as well which make for a generally dynamic composition. That is overlaid by a jazzy score of accompaniment courtesy of Krzysztof Komeda, a future collaborator on many of Polanski’s subsequent works during the ’60s.

Thus, it becomes an exercise of technical skill, much like Hitchcock in Lifeboat or any other film that limits itself to a single plane of existence. Polanski’s framing of his shots with one figure right on the edge of the frame and others arranged behind is invariably interesting. Because although space is limited, it challenges him to think outside the box, and he gives us some beautiful overhead images as well which make for a generally dynamic composition. That is overlaid by a jazzy score of accompaniment courtesy of Krzysztof Komeda, a future collaborator on many of Polanski’s subsequent works during the ’60s. However, at this point, as a young director, he is simply sharpening his teeth and getting acclimated to the genre a little bit. Knife in the Water builds around the three sides of a love triangle, creating a dynamic of sexual tension because that’s what tight quarters and jealousy do to people. This is less of a spoiler and more of a general observation, but the film does not have a major dramatic twist. Instead, there are heightened tensions, a bit of underwater deception, and finally a fork in the road.

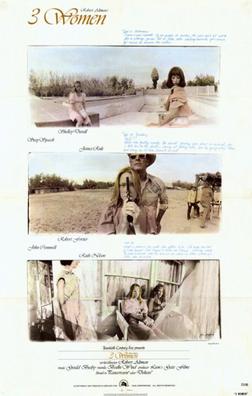

However, at this point, as a young director, he is simply sharpening his teeth and getting acclimated to the genre a little bit. Knife in the Water builds around the three sides of a love triangle, creating a dynamic of sexual tension because that’s what tight quarters and jealousy do to people. This is less of a spoiler and more of a general observation, but the film does not have a major dramatic twist. Instead, there are heightened tensions, a bit of underwater deception, and finally a fork in the road. Supposedly Robert Altman’s inspiration for 3 Women came from a dream he had, as with many of the most original ideas out there. Admittedly, in some ways, the resulting project feels like his rendition of a European art-film. It has some roots in Bergman and Polanski while transposing the action to his usual locales that are inbred into the fabric of America — places like the California deserts and Texas.

Supposedly Robert Altman’s inspiration for 3 Women came from a dream he had, as with many of the most original ideas out there. Admittedly, in some ways, the resulting project feels like his rendition of a European art-film. It has some roots in Bergman and Polanski while transposing the action to his usual locales that are inbred into the fabric of America — places like the California deserts and Texas.