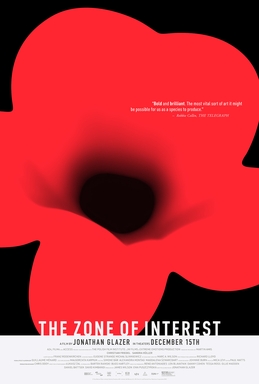

Zone of Interest opens with a blank screen and a collage of sound; it’s almost like it’s priming us for the movie ahead. Because it’s not a conventional movie by any stretch of the imagination. It’s difficult to put arbitrary labels like good and bad on it since it’s so different than what we normally get in the cineplexes.

Zone of Interest opens with a blank screen and a collage of sound; it’s almost like it’s priming us for the movie ahead. Because it’s not a conventional movie by any stretch of the imagination. It’s difficult to put arbitrary labels like good and bad on it since it’s so different than what we normally get in the cineplexes.

However, for some time the name Jonathan Glazer has become synonymous with singular visions often lauded and simultaneously prone to divisive reactions. There’s also the subject matter. Zone of Interest is loosely based on the eponymous novel by Martin Amis.

We effectively enter the movie by watching the daily life of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Hoss (Christian Friedel) and his wife and kids. Observations become so key to the cadence of the movie because the entire film is built out of the structure of their lives and the world they have created. It just happens to butt up against one of the most horrendous atrocities known to man, and we have to contend with this as an audience even if they will not.

When you pick up various mundane insights, you appreciate the understatement of what is being portrayed and then instantly turn grim with each subsequent realization. There’s something disorienting about the shots within the home almost like surveillance footage and the angles are not human perspectives. Outside the tracking shots are more natural but no less perturbing.

The mother Hedwig (Sandra Huller) is frumpy and flat-footed as she tends her garden and settles into a life mostly oblivious of everything around her. The kids play with their toys and have breakfast and dinner like any children. Except they examine human teeth by torchlight or mimic the unearthly humming thud of what can only conceivably be from the human ovens next door.

It’s all this inexplicable darkness that lives on the fringes of the movie’s frame denoted primarily by sound in the periphery, ashes laid down in the soil, remains in the river, even passing remarks about leftover clothes that have been picked over.

The metaphor is fairly obvious, but the family has built this garden as a buttress and an oasis against the camp next door. This is how they can celebrate their father’s birthday and have pool parties while people are being shot and murdered just meters away from them. This is not normal. Some kind of compartmentalization and moderate delusion has to be accepted for such localized dissonance to exist.

Gardens and flowers are meant to represent beauty and cultivation in the natural world, and yet there is something distinctly afoul with this coming into being from the ashes of the murdered. Sometimes this cycle of life is spun and explained away as a natural process, but in this case, it’s a bald-faced lie.

Hedwig says this is their Lebensraum — the “living space” Hitler promised to his Aryan followers when he came to power. For her, be it ever so humble and grotesque, there’s no place like home. And so while Hoss gets a promotion to oversee the efficiency of the camps all over Germany, she asks to stay in her home. She’s happy there. Living off the detritus and skeletons of the dead. She wants to continue to tend to her garden.

On several evenings while Hoss reads fairy tales to his kids, there are otherworldly thermal vision sequences of a young woman leaving out apples and other gifts of sustenance for the prisoners to find. Purportedly this is based on a real-life young member of the Polish underground. It’s one solitary inkling of goodness amidst the queasy, uneasy status quo of the movie. Without it would be easy to suffocate under the pressure or worse still become apathetic.

It seems like there must be a caveat with Zone of Interest. We must be vigilant and careful because there is an insidious nature to the story, whether it’s intended or not. It’s possible to get caught up in the plans of these men in boardrooms and offices especially when we move away from the camp itself. Because even if we never get inside, there are touches and the grim noisescape that never allow us to lose perspective entirely.

But whether it’s Hoss and his wife having a marital tiff or him vying for greater status within the Nazi killing apparatus, these moments can draw us in with a kind of hypnotic power. I’m not sure if they are instructive unless they lead us to one particular end.

It’s easy to trot out the idea, but with the brief mention of Adolf Eichmann within the film itself, it feels even more imperative to evoke Hannah Arendt’s famed phrase from the Eichmann trial: The banality of evil.

By now it comes off the tongue so easily it can sound cliché, and yet it’s never been so true as watching this film. The efficient nature of the crematoriums is methodical if it weren’t so ghastly. It’s the first of many touches reminding us precisely what we are witnessing in real-time. I think we want it to feel worse or more extraordinary than it comes off. Somehow it would make it more comforting — that there is a large gulf between the predilections of my own self-serving heart and these people — still, there’s no such luck.

In one particular moment, the screen is momentarily enveloped in red. It might have many reasons, but all I could think about was the blood that has been shed. It’s almost second nature to see this as blood on the hands of others, and strictly speaking, this might be true. However, I’m not presumptuous enough to forget my own sins of commission as much as omission. It almost feels like a rite of passage for human beings. None of us are clean. We all have blood on our hands one way or another even if we were only born into it.

I was talking to a friend who mentioned how we get a ground view of what mechanized evil looks like when people work together for a collective purpose — in this case a horrific end. What would it look like instead if a community gathered together with this kind of collaboration and vigor for the sake of good? It’s an intriguing question and since my mind leans toward hope, I wanted to consider it.

I’m sure he meant it in a broader sense, but my mind went to Le Chambon. The particulars are a little murky, but from what I remember the French village worked together as a community to harbor and save 100s of Jewish lives. Now there may be nuance to the story — particular individuals who led the charge (see André Trocmé) — but that’s partially what it takes. It’s the captivating idea that small acts and decisions have a cumulative power. We can just as easily stand strong as we can capitulate and cave one day at a time.

Near the end of the movie we flash forward to the present day where museum attendants clean the exhibits, and there’s a different kind of sound design as we go through the cavernous spaces and see the scope of the destruction leveled against the Jewish people. This is our first and only glimpse of these spaces from the inside.

The movie does something curious by cutting back to Hoss as he straightens up after doubling over on a stairwell having just thrown up. Is it an ailment or is it somehow related to the work he is doing — the thousands of lives he will effectively snuff out echoing through the ages. It’s difficult to impute such sympathetic thoughts to a man we have watched in such a rudimentary light. I’m not sure what to make of it.

The movie goes out the way it came in with a blank screen and almost avant-garde sound design. But rather than put a label on it, it seems more conducive to express the emotions it elicits. It feels unnerving, a bit like you’re watching a horror film because there’s something layered and unnatural about the noise. But then that’s precisely the point.

4/5 Stars